We’ve all heard the adage about something being “As American as mom and apple pie,” but have you ever heard of Vinegar Pie? While researching in the Colorado Historical Newspapers Collection, I encountered this unusual alternative to our national favorite in the May 16, 1905 issue of the Leadville Herald Tribune. The title gave me pause. Historical recipes occasionally fall through the cracks of time as tastes shift, ingredients become more or less available, and, in some cases, simply because they’re not very good. Could a concoction such as vinegar pie actually be enjoyable? What sort of pie is it, exactly? All things being worthy in the name of historical research, I decided to bake the recipe and share the results with you here.

As any good baker or cook will tell you, before undertaking a new recipe, it’s important to read and fully understand the instructions in advance. Woe to the baker who begins a sweet treat on the morning of a special occasion, only to make it halfway through and find the dreaded “refrigerate overnight” instructions!

Baking success is also sometimes dependent on knowing the historical context of your dish, particularly when creating a dessert described more than one hundred years ago. As an example of the challenges posed by historic recipes: you will often find that specific temperature and bake time prescriptions are missing entirely.

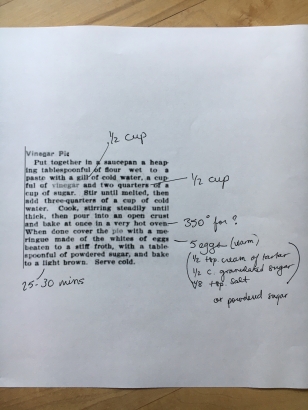

Vinegar Pie circa 1905 did indeed require some historical consideration, reasoned guesswork, and significant vigilance. Let’s break down the formula of our historical document and examine what challenges it presents. The following is my annotated version of the recipe:

A quick google search turns up that a gill is ½ cup. For the vinegar, we’re going to assume for sanity’s sake that this is an actual cup measurement, and not a teacup or other container. And why in the world would they say “two quarters of a cup,” instead of the simpler “half?” Might our baker have possessed only a ¼ cup measuring tool?

“Stir until melted, then add three-quarters of a cup of cold water. Cook, stirring steadily until thick, then pour into an open crust and bake at once in a very hot oven. ”

The astute reader will note there is no cook time mentioned, nor analogy to what the mixture’s thickness should look like. To the modern eye it seems like we’re making something similar to lemon curd here. Unfortunately, it wasn’t until after I had already poured only somewhat thickened vinegar liquid into the crust that I realized this fact. Also, the original author clearly assumed a pie crust was sitting around ready for use (and did not provide a recipe for one). I reasoned that if they can have crusts just sitting around in case of need, so can I, so I cheated and used a pre-baked graham cracker pie crust (ah, the perks of the modern grocery store).

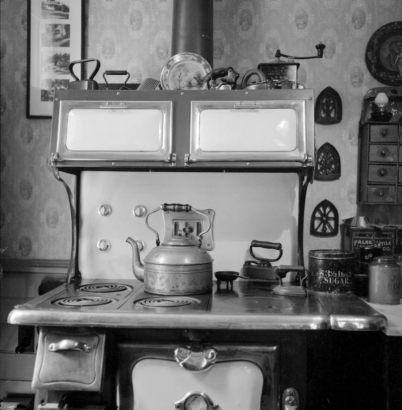

Turning to the questions of how long, and how hot, to bake the pie on this first round, a little further guesswork comes to play. Assuming the baker in 1905 would’ve been using a wood-burning or early gas stove, the lack of specifics makes some sense: they could not have simply set the oven to a constant temperature, and thus the bake time could vary widely. A hot oven would just have to be a hot oven, and one would have to keep an eye on things.

After some internet and cookbook sleuthing, and in the interest of convenience, I decided to treat this pie like a lemon meringue pie, and so investigated the typical temperature and bake time for those. For the pre-meringue baking round, I settled on 350° (350° is “hot,” right?) and 20 minutes, plus a few extra to account for altitude. While I was baking at a mile high, our Leadville baker would've been at nearly two miles! Perhaps the lack of bake time wasn't terribly relevant, after all. While the undercooked vinegar curd baked, I turned to the meringue.

“When done cover the pie with a meringue made of the whites of eggs beaten to a stiff froth, with a tablespoonful of powdered sugar…”

As a meringue novice I only had a vague idea of how you make meringue. How many eggs do you use for a pie? Do you really add only powdered sugar? It was time for more research!

Finding the following recipe that suggests using five eggs, and this one that lists the number of minutes you cook a two-egg or three-egg meringue, I calculated the meringue pie would need to bake for around 21 minutes, plus a few extra for altitude.

But first I would need to whip the eggs into stiff peaks. In keeping with a historical recipe, I opted to ignore modern additions of cream of tartar, and also to whip my room-temperature egg whites by hand. Five very aerobic minutes later, with sadly unfrothed eggs, laziness won out and I grabbed the electric hand mixer. After another five to seven minutes, I had beautifully peaked egg whites. Bakers of the early 20th century must’ve had phenomenal arms from all of that whipping!

“…bake to a light brown. Serve cold.”

This moment is where I most came to appreciate the beauty of modern recipes that list time and temperature. In order to make sure I didn’t scorch the heck out of my pie, I was peeking in on it every few minutes. Multi-tasking to prepare different dishes, hand wash clothing, or tend to children or farm animals would not have been an option. Bakers in 1905 really had a harder lot than us.

When my meringue looked set and perhaps a smidgen too toasted I removed the pie to cool (incidentally, this was 20 minutes in, thank goodness for my watchful eye). Ignoring that my curd was more of a viscous liquid than gelatinous solid, the first taste went like this, “WOW, that’s a burst of interesting flavor! It’s sweet and sour without being bitter!” Followed by, “something tastes metallic…what is that aftertaste…oh no, no, no this won’t do.” The pie ended up in the garbage can.

Overall, this experiment was a lesson in how tastes change, and how modern conveniences have perhaps made us a bit too complacent in the kitchen. This recipe did not allow me to operate from a place of trust. As a hobby baker, I have never examined a modern recipe to the degree I did this one, but fortunately, the internet and our digital collection were helpful tools. Overall, today we can avoid constantly checking on the pie in the oven; although truth be told, you are less likely to burn your efforts with old-fashioned “constant vigilance!”

A further bit of historical knowledge might allow me to improve upon my first test. The Colorado baker of 1905 may have been more likely to use apple cider vinegar than the white version. White vinegar is fermented from grain alcohol (also an ingredient in the significantly dearer drinking whiskey), but apple cider vinegar is fermented from apple cider, or from a similar substitute called “apple scrap vinegar” that one can easily make at home. Apple husbandry and orchards were a common feature in Colorado during the early part of the 20th century, and so our recipe author may have had apple cider vinegar closer to hand.

If any of our readers are game to try the recipe with apple cider vinegar, or even to try this drastically different modern version, please let us know how it goes! In the meantime, I’ll be sticking to apple pie.

Comments

The poor child in the first

The poor child in the first photo looks like she knew what was coming.

Hi Craig, thanks for your

Hi Craig, thanks for your comment. She certainly does, and the adult woman looks so menacing! I promise I did not force anyone to eat this pie.

No credits for your

No credits for your photographer?

Hi Paul. Thanks for your

Hi Paul. Thanks for your comment. The color photos were taken by someone in the Senturia household who wished to remain uncredited. For the historic photos, you’ll find that if you click on them, the pop-up this produces includes an info link directly to the image in our digital collection. Thanks for reading!

What a fun experiment! It is

What a fun experiment! It is always tricky to figure out those old recipes. We make vinegar pie at the Littleton Museum as part of our foodways program on our 1860s living history farm. It is really very delicious and the recipe we use does not call for meringue on top. The consistency is similar to a chess pie, and if you try this again, cook it at a higher heat-425 degrees. We cook ours in a dutch oven using coals from the hearth so we don't use exact temperatures and we leave the pie in the dutch oven adding more coals as necessary until the pie tests done. You are supposed to use apple cider vinegar as that would have been most common in the 19th century and easily made if you grew your own apples and pressed them in the fall. I encourage you to try this recipe again.

Suellen, thank you for the

Suellen, thank you for the encouragement. Your version of the pie sounds much more enjoyable, as does the experience on the farm! Glad to hear my guess about apple cider vinegar was correct. I'll try another round (and will come visit the museum)!

In the book Sourdough

In the book Sourdough Biscuits and Pioneer Pies by Gail L. Jenner, p. 70, there is a recipe for Vinegar Pie. It is similar, but uses 1/4 of sugar and 1/4 cup of molasses to a ratio of just 2 Tablespoons of vinegar in the filling. The author does not date the recipe, but says that it comes from a collection dating to the late 1800s. If you are interested in trying again it might be a more palatable result.

Thank you, Matthew! Yes, I

Thank you, Matthew! Yes, I will certainly give this one a try. Have you made it yourself? If so, how was it?

I remember my mother talking

I remember my mother talking about a "hot oven" or "slow oven" etc. So I checked Wikipedia and sure enough there is a table of temperatures along with those kinds of descriptions. It says a "hot oven" is 400-450 F, so Suellen's 425 degrees fits right in there. And definitely apple cider vinegar. https://en.wikipedia.org/wiki/Oven_temperatures

Thank you for sharing, Linda!

Thank you for sharing, Linda! I love this description from the wiki page, "Cooks estimated the temperature of an oven by counting the number of minutes it took to turn a piece of white paper golden brown...."

So fascinating how folks "made do" in the absence of regular measurements.

Add new comment