For thousands of years, Venezuela was inhabited by tribes focused on hunting and fishing that were related to other tribes in the Caribbean like the Taino of Cuba and Puerto Rico. There were also native people practicing agriculture high up in the Andes mountains of Venezuela. The nation’s name was given by Christopher Columbus, who saw homes on stilts above the water and named it “little Venice”. The first Spanish settlement was established in Cumaná in 1523, but other colonial powers like the Germans, Dutch, French, and English also attempted to exploit the region’s resources. Under the leadership of revolutionary Simón Bolívar, Venezuela, Ecuador, and Panama freed themselves of Spanish rule and formed the nation of Gran Columbia. In 1830, Venezuela would break off as an independent nation. In 1928, after nearly a century of bloody struggles over slavery, voting rights, the power of the church, and foreign investors, Venezuela emerged as the top oil exporter in the world. This led to greater investment in infrastructure but also gave way to a series of dictatorships.

It would not be until 1969 that a government in power would give up power peacefully to the winners of a democratic election. A series of presidents, including Caldera and Pérez would begin nationalizing various industries like oil and minerals. Profits led to a boom and reinvestment in the country, but that came crashing down as oil prices continued to fall in the late 1970s, through the 1980s. In 1992, a coup was led by army officer Hugo Chávez. While the coup failed, Chávez would come to win the presidency in 1998 as more than half the population fell below the poverty line. Major Venezuelan immigration to the US began in the 1980s with the economic crisis and continued through the decades of Chávez’s rule as he became increasingly authoritarian and the economic situation failed to improve. He died in 2013 only to be replaced by his hand-picked successor, Nicolás Maduro. The Venezuelan born population of the U.S. would rise from 33,000 in 1980 to 770,000 in 2023 with the vast majority living in Florida.

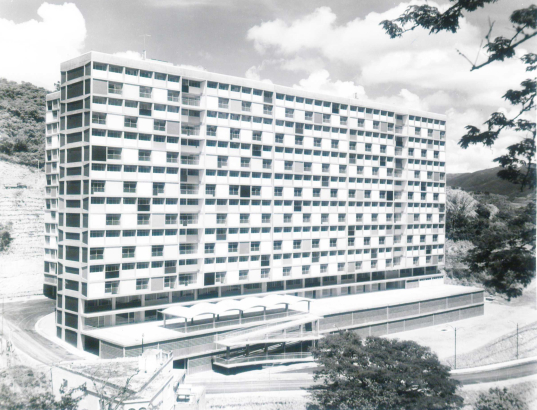

While Colorado has never been a primary destination for Venezuelan immigrants in the U.S., they have been living in Colorado since at least 1935. One of the first Venezuelans we found in Colorado was an engineer named Ralph Delgado. He lived and worked as an engineer in Fort Collins in 1935 prior to moving to Texas. By 1950, academics arrived here like Jerome Sotillo, who attended classes at Regis University, and John Hidalgo, who lived in Morrison while doing medical research for University of Colorado. Most Venezuelans would not arrive for many decades later, however a small minority continued leaving its mark on Colorado.

Juan Rodriguez was born in Cuba and raised in Venezuela. After earning a master’s degree from New York University in 1963, he took a job with IBM and moved to Colorado in 1966. In 1969, he teamed up with Palestinian immigrant Jesse Aweida to start up a new high-tech data storage company. The new company, Storage Technology, came to be known as StorageTek. When the company began dismantling its optical storage division, Rodriguez and a few other colleagues left to found a new computer-tape storage company called Exabyte. He held the position of chairman and CEO until his retirement in 1990.

“Juan is a dedicated family man, loyal to his friends and employees,” Hill said. “Many entrepreneurs can look at the world with a cold, cruel perspective - they can be pretty ruthless. That's the exact opposite of Paul.” - Rocky Mountain News May 14, 1991

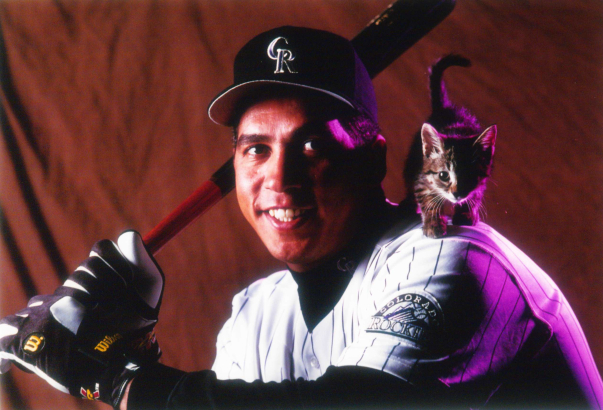

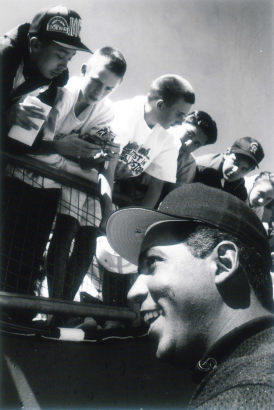

One of the common bonds between the U.S. and Venezuela that dates back at least a century is their mutual love of baseball, which led to a growing roster of Venezuelan players being recruited onto U.S. teams. One such player was Andres Galarraga. After seven years in the National League, Galarraga signed on to the Colorado Rockies in 1992. The next year, he became the first Venezuelan and first player on an expansion team to become the National League’s 1993 batting champion with a .370 average. During the off season, he enjoyed visiting his home in Caracas to connect with family and often wore a t-shirt with the Venezuelan flag under his uniform during games. He went on to play for several other baseball clubs, including another stint with the Rockies, until his retirement in 2015. The Rockies have since brought on other Venezuelan players such as Jonathan Herrera and Carlos Gonzalez.

In a society with diverse immigrant groups, food becomes a common language. That's true in Leadville, where Venezuelan entrepreneur Awedis Banojakedjian opened a popular carniceria that caters to the many Latino families who made their home in the historic mountain town. In Denver, baker Imael De Sousa even drew the attention of Bon Appétit Magazine with his “golfeados”. De Sousa was born in Portugal, raised in Venezuela, and studied culinary arts in Florida before opening Denver’s Reunion Bread Company in 2019. It was here that Bon Appétit discovered and applauded his unique version of a Venezuelan sticky bun.

“It was a shower of what I later found out was cotija cheese that secured this golfeado’s spot in my personal pastry pantheon,” [Amiel] Stanek wrote for the food magazine. - Denver Post September 15, 2019

In 2022, the combination of an increasingly authoritarian Maduro government and the impacts of U.S. sanctions on Venezuelan oil sent the humanitarian situation spiraling. This led to a large increase in Venezuelans escaping to other South American countries, Mexico, and the U.S. to apply for asylum. Busloads of people coming from border towns to Denver, often sent under false pretenses by the Texas government, coupled with serious cold weather led to a sudden need for emergency shelters. Organizations like the City of Denver, American Friends Service Committee, Casa de Paz, and various churches came together quickly to provide shelter. Before long, families were able to find jobs and/or move on to their families already living in Colorado and elsewhere in the country. One such family was Karelys Espinoza, Luis Rodriguez, and their son, Luis Jr. When Denverite interviewed them in early 2023, they were celebrating Luis Jr.’s second birthday in their new apartment thanks in part to the Colorado Housing Asylum Network (CHAN). Luis Sr. had escaped the Venezuelan military, where he was expected to attack protesters and anti-government dissidents. They feared having their children kidnapped by the government and sought refuge in the United States. The head of CHAN said of this new immigrant cohort:

“We are hearing their kids are just fantastically doing well in school. They're finding work, they're connecting with each other, they're helping each other, they're helping the people who are coming after them.” - Denverite May 10, 2023

While Denver has never been a primary hub for Venezuelan immigrants, the 2024 Trump campaign endeavored to demonize the entire community by claiming Venezuelan Tren de Aragua gang members had taken over an apartment complex and, at times, even claimed they had taken over the city of Aurora. According to Aurora police officials, there was little to no Tren de Aragua presence in the city. The apartment in question was owned by New York-based CBZ Management and had years of code violations over their poorly maintained properties. It was late 2024 when the city planned to shut down one of their properties. The company immediately hired a public relations firm who made the claim that the Venezuelan gang had taken over. The Trump campaign continued to refer to Aurora as a “war zone” even though crime had been on the decline since 2022. In the words of Will Dempster, representing the National Immigration Law Center,

“Our communities are not political pawns or scapegoats, and we take care of one another no matter where we were born, the color of our skin, or how much money we have. Anti-immigrant hatred has no place in Colorado.” - Colorado Newsline October 11, 2024

Many Venezuelans were granted temporary protected status, which enabled them to obtain work permits and start the legal process to request asylum. The administration attempted to remove this status in 2025, and, pending a final decision in the Supreme Court, the lower courts have ruled it an overreach by the Department of Homeland Security. However, fear has driven many Venezuelans and others starting new lives in the United States to flee or go underground.

Facing great challenges, many families and communities are still working to ensure people can remain and bring their hopes to fruition in their new home. Colorado Public Radio interviewed several families anonymously in late 2025 to relay their experiences. One man was managing a factory, raising his U.S.-born children, and studying for his master’s degree. Another woman and her husband fled Venezuela due to death threats. They saved money to buy a home in Denver and their child is now attending University of Colorado with a full scholarship thanks to their outstanding academic performance. Like many newcomers, the Venezuelan community has dealt with open bigotry and hostile government policies, but are also bolstered by the same strength required to leave one’s homeland and start life anew. Their strength and tenacity will continue to enrich Colorado and exemplify what it means to be an American.

Further reading:

Denverite Article on Venezuelan Immigrants

How false claims of a ’complete gang takeover’ drew Trump to Aurora

Add new comment