In the not too distant past, I posted a blog exploring several aspects of old-time advertising. In addition to being great fun to research and discuss, it was also quite well-received. As such, I’m quite pleased to report that the topic will be a recurring theme in my blogging itinerary, but with a bit more of a focused approach rather than the sweeping and all-inclusive tack taken in the first entry. With that, let’s talk about some “female weaknesses,” shall we..?

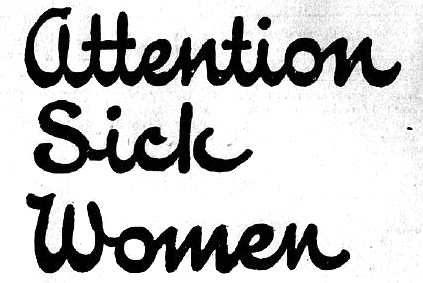

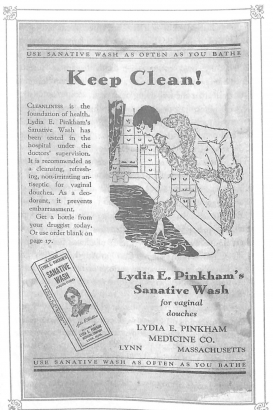

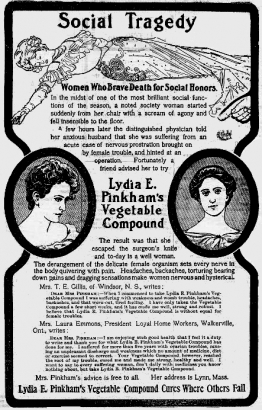

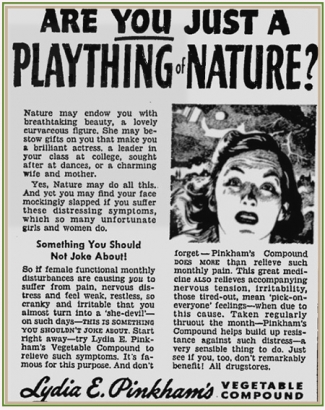

In the late 1800s, ads touting “guaranteed” cures for virtually every disease known to mankind (and a few that weren’t) were peppered throughout most newspapers. “Female ills” were one of the more common targets of advertising (alongside its male counterpart “exhausted vitality”), and if the ads were to be believed, most women of the day were little more than bedridden invalids owing to their delicate constitutions. (I’m eternally grateful that I live in an era where such infirmity has been largely left in the dust.) While many treatments for these ailments were proffered, with some attaining a degree of notoriety (or infamy), perhaps none were as ubiquitous or pervasive as Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound.

As with many other tonic purveyors of the patent medicine industry, the formula itself wasn’t actually patented (only the packaging), leaving them free to alter the composition of the compound if needed. One aspect of the treatment that did set it apart from many of its contemporaries, however, is that it didn’t begin as a money-making scheme. Lydia had been providing her medicinal compound to her friends and neighbors for years, free of charge. A real estate crash in 1873 left her husband (and by extension, her) in deep financial trouble, leading to her apparently reluctant decision to put her product on the open market. Whatever recalcitrance she may have initially held, it apparently quickly faded away.

The local market was quickly saturated, so Lydia and her husband Isaac mortgaged their home, and $1000 of those proceeds were hauled to New York City by their son Daniel to plunk down on advertising. It’s unlikely they had any notion of the empire they were founding. Lydia died in 1883, but by that time the business had taken on a life of its own, and was by all appearances an unstoppable juggernaut. To give you some idea of just how prevalent her advertising became, searching the keyword “Pinkham” on the Colorado Historic Newspaper site yields nearly 7000 results between 1880 and 1905 (and almost 27,000 if no date range is selected). Considering this is an (as yet) incomplete record comprised of papers exclusive to Colorado, and it doesn’t even include major publications like the Denver Post or Rocky Mountain News, you should garner some insight as to just how inescapable the ad campaign was.

Another thing which set the product apart from many of the other remedies on the market was that it was actually somewhat efficacious (or at least not harmful). That’s not to say that it treated or cured every ailment it wound up being associated with (based largely on testimonials… a subject for another time), but in terms of relieving discomfort associated menstrual cramps or menopause, there’s some evidence it was actually successful. The fact that it was roughly 20% alcohol probably didn’t hurt its sales, either—particularly during prohibition. Unlike some of their counterparts, the fact that they were able to show some redeeming medicinal value to their potion allowed them to keep selling it even during the reign of the Volstead Act.

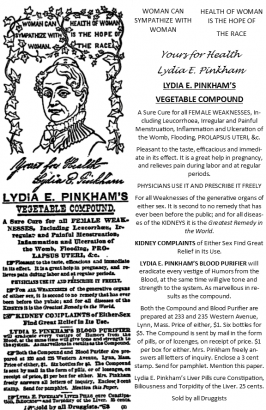

In addition to the vegetable compound, the company began branching out and providing other folk remedies, though none gained anywhere near the popularity of the original. In addition, Lydia encouraged people (particularly women) to write for advice on women’s issues, a practice which continued long after her death (though many seeking her advice were unaware of this fact). In a sense, she became a precursor to advice columnists like Ann Landers. She never charged for her advice, though it’s unlikely that she was reluctant to recommend a bottle or two of Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound where applicable. Because of this, she became far more than a mere figurehead for her company, but a strong voice for women’s rights (but these, too, are subjects for another time).

This still barely scratches the surface of Lydia Pinkham’s enduring legacy. There are many more aspects of her life and impact left to explore, some of which I’ve hinted at here. If you can’t wait for the next installment, feel free to pay a visit to the Western History and Genealogy department. We have a massive collection of newspapers on microfilm, guaranteed to have a wide selection of her ads scattered throughout. In addition, you might be interested in perusing Elbert Hubbard’s brief but informative Lydia E. Pinkham: Being a Sketch of her Life and Times, or Suzann Ledbetter’s more expansive Shady Ladies: Nineteen Surprising and Rebellious American Women.

*NOTE: Clicking on the images makes them significantly more legible.

Here's a link to part 2

Comments

I absolutely love this!!

I absolutely love this!!

Well, thank you so much!

Well, thank you so much!

This is so excellent I hope

This is so excellent I hope you won't mind if I suggest you replace "tact" in the first paragraph for the work "tack" which is what I am sure you mean. I know you will want it to be perfect.

Thank you, Mysterious

Thank you, Mysterious Stranger!

For the record, I never strive for perfection... I'm generally satisfied if I can surpass "adequate."

Brilliant! Love your

Brilliant! Love your articles.

Thank you much!

Thank you much!

Add new comment