The following is the second part of the exploration of the legacy of Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound (the “part 2” in the title probably clued you in on that fact). If you missed out on the first part, I would encourage you to read it first.

In 1692, a young woman named Mary Tyler spurned the romantic advances of a man named Timothy Swan. In a twisted act of retribution for this dismissal (sadly consistent with the era and region), Mr. Swan had her arrested. Mary was loaded into an ox cart, and hauled off to Salem, Massachusetts to stand trial for (and ultimately be convicted of) making a covenant with the Devil, and casting a vicious spell on poor master Timothy. Mary spent the better part of the summer locked in a cell, but fortunately for her, 'witch hunting' had fallen a bit out of favor by that time, so her execution never went through. Mary was ultimately given a small stipend as recompense for being inconvenienced, and allowed to return to her home at Boxford House, where it is rumored her kindly, unassuming spirit still dwells to this day.

You may be wondering what, exactly, this has to do with Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound. In truth, not much other than the fact that Mary was a distant relative of Isaac Pinkham, Lydia’s husband, and it was such an odd bit of trivia, I felt the need to shoehorn it in somehow. Now that I’ve sated that urge, let’s move on.

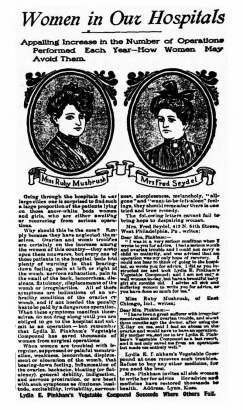

Customer testimonials played a large role in patent medicine advertising, and Lydia Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound certainly embraced this trend, if not actually leading the pack. You might be tempted to believe these were frequently fabricated, or intentionally fraudulent, but that’s not actually the case. Obtaining glowing recommendations from the public was fairly easy, as was garnering permission to reprint said correspondence. In fact, many of her ads (as the one above) boasted a $5000 reward if anyone could provide evidence that the testimonials were either invented, or printed without consent.

Getting your picture and letter printed in newspapers throughout the United States and Canada, even if associated with an advertisement, must have been the rough equivalent of having your tweet go viral. Including hyperbolic claims and emphatic language undoubtedly increased the odds that a letter would get chosen for publication. (It likely wouldn’t hurt to mention the name of the product at least twice, too.) That’s not to say that the correspondents were necessarily lying, merely that they understood that saying “your product helped a little” wasn’t likely to draw much attention. It’s also pertinent to note that in the majority of cases, the ailment was self-diagnosed, as was the cure.

For their part, manufacturers were more than willing to take any positive claims at face value, and would often incorporate said claims into future advertising, bolstering the ever-growing list of maladies their miracle product “cured.” This wasn’t quite as prevalent with Pinkham’s compound, largely because it was marketed exclusively to “women’s problems” rather than as a panacea. However, there were a number of assertions in this realm (such as curing cysts or even ovarian cancer) which were often taken to heart. Perhaps the most common, completely unsubstantiated statements had to do with fertility. Pledges that someone couldn’t get pregnant, then drank the tonic, then got pregnant were fairly commonplace, but undoubtedly fall under the purview of the post hoc, ergo propter hoc fallacy (X happened after Y, therefore Y is the cause of X). To be fair, it’s not exactly unheard of for alcohol to have played some role in a pregnancy or two.

I should be clear that many of the letters sent to the Pinkham Medicine Company were not intended for self-aggrandizement, nor even for public consumption. As was previously mentioned, Lydia encouraged people to write with any questions regarding women’s health issues, and while this was probably in part a tactic to drum up business, it also served a legitimate need. During the 1870s when communications were first solicited, an astonishing number of people—men and women alike—were oblivious to such basic biological truths as menopause. Lydia even wrote a two books (Yours for Health and Married Women and Those About to Be) covering most aspects of sexuality, reproduction and female physiology. Both books were given away for free, as Lydia firmly believed that healthy and informed women were vital to the strength of the nation.

Long after Lydia’s death, advertisements still encouraged women to write “Mrs. Pinkham” for advice. A 1902 issue of Ladies Home Journal (an outspoken opponent of patent medicines) published an article ‘exposing’ Lydia’s demise nearly 20 years earlier, offering a photograph of her engraved tombstone as evidence. The company quickly responded, stating they had never intended to be deceptive, and that the “Mrs. Pinkham” mentioned in their advertising was in fact Jennie Pinkham, Lydia’s daughter in law. Whatever the repercussions were, they didn’t impact the sales much. Pinkham’s Compound went international before the start of World War I, and in 1925 reported a whopping four million dollar gross income (the rough equivalent of 55 million today).

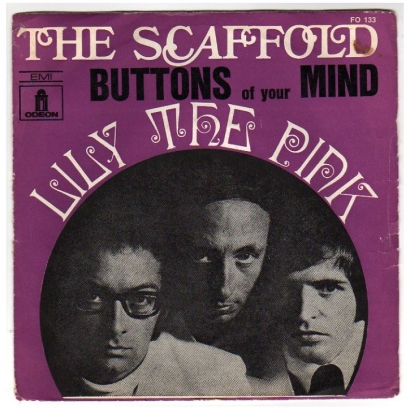

Though the popularity and prevalence of Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound waned as time went by, not coincidentally taking a sharp downward angle shortly after the FDA was formed, its influence certainly remained. During prohibition, the 40-proof tonic inspired a bawdy drinking song called The Ballad of Lydia Pinkham. Decades later, in 1968, the band The Scaffold released a slightly less lurid version of the song titled Lily the Pink… it became a chart-topping hit. (Incidentally, The Scaffold is probably best known for the fact that one of its members, Mike McGear, was actually Peter Michael McCartney—brother of the famous Paul. He’s the one on the right.)

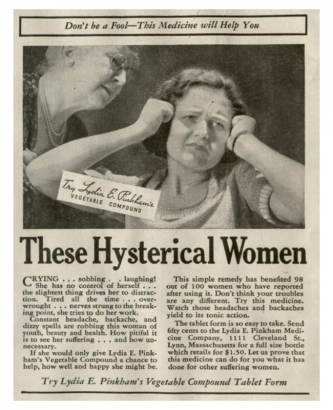

Often imitated but never replicated, Lydia E. Pinkham’s Vegetable Compound is arguably the most enduring relic of the patent medicine era. Ultimately the company was sold, the formula was altered, and the alcohol was eliminated, but the compound is still available today (though it’s now marketed as an Herbal Supplement, rather than Vegetable Compound). Something to keep in mind, perhaps, should you or someone you know succumb to nervous prostration. It’s kind of a shame the ad campaign, one of its most iconic elements, didn’t make it quite this far.

If you enjoyed this post, and would like to see more of this kind of thing, please like our Western History and Genealogy Facebook page. Thanks!

NOTE: Clicking on the images makes them significantly easier to read.

Add new comment