Colonization through World War I

From the earliest days of Colorado colonization, the need for labor and the raw numbers needed to achieve statehood were front of mind. Both the post-Civil War period and the turn of the century saw particular calls for farm workers coming from Colorado as well as other states. In 1899, for example, the Loveland Register noted that, despite access to rail travel and employment agencies, there were simply not enough workers to fill farmers’ needs. By 1916, the Federal Employment Bureau was working to place men and even entire families with farm owners, but continued to come up short. According to the Rocky Mountain News,

“Statistics recently compiled by the federal department of labor show a shortage of farm help thruout the country, and this shortage, it is stated, will be even more pronounced during the coming season.” Rocky Mountain News February 25, 1916

In 1917, reliance on migratory labor continued to increase. The Chinese Consolidated Benevolent Association was offering the US government 500,000 Chinese laborers that would be deported back to China as soon as the country no longer needed their wartime labor. The plan never saw fruition and farms continued to rely on migrant labor from within the US and south of the border. At this time, Weld County alone was announcing its desperate need for 5,000 workers due to a prolific crop. After the war and into the 1920s, the shortage continued as many laborers moved to better-paying jobs in the cities. 1920 marked the first year that most Americans would be identified as urbanites. The following year, the Greeley farmer’s association announced they were cutting wages. By 1927, farm workers were reported to be receiving the lowest wages in the nation.

“Farm hands who work for wages alone and board themselves receive about $48.47 a month. The farmer who boards his help allows approximately $14 a month for this expense, the data showed.” The Great Divide April 20, 1927

Tenant Farming and the Great Depression

The Great Depression and Dust Bowl that followed in 1934 led to many small farmers losing their land to corporate owners that could buy them up from the banks. In 1931, a study of beet farms, farmers, sugar beet companies, and laborers was conducted by the Third Catholic Conference on Industrial Problems. The report found that 70% of the farmers were tenants on leased land. The sugar companies had annual contracts with the growers for a fixed price per ton. In 1931, the companies decided to cut the price per ton by 21%, which, according to the report, was mostly arbitrary and due to the fact that the large numbers of unemployed workers would lead desperate families to work for pennies. An estimated 32,000 Russians, Mexicans, and other Latinos would be impacted.

“No family can exist on the wages paid to beet field labor this year. To expect them to do so is cruel and inhuman.” - Industrial relations in the beet fields of Colorado, 1931

And so the dilemma of where to find labor willing to toil for such insufficient wages continued to grow.

Colorado's Border Closure and the War Years

On Saturday, April 18, 1936, Governor Johnson made an official declaration of martial law. He ordered the Colorado National Guard to patrol the state's entire 360-mile southern border. Governor Johnson invoked the evergreen image of a "threatened invasion of alien and indigent labor." At the same time, he empowered the military to determine if those crossing the border did so with obvious financial means. Americans who were verified to be wealthy enough for purposes of commerce or tourism were to be allowed in. Lines of cars were backed up at the border with New Mexico to be questioned by Colorado National Guardsmen. For ten days, Colorado was closed to immigrant workers and the poor alike. The Depression saw massive deportation efforts and people focused their economic anxieties on the foreign born workforce.

By 1942, things had changed dramatically and the federal government established a formal agreement with Mexico to bring in more agricultural workers. This came to be known as the Bracero Program. The May 2, 1943 edition of Denver Post even reported that the US State Department was celebrating the 15,000 agricultural workers already in the US to harvest crops while much of the country was engaged in World War II. Colorado asked for 10,000 Mexican workers that same year.

“These workers have a high patriotic motive. They are Spanish type Mexicans, highly intelligent and experienced in agriculture. They are leaving families at home to come up here for several months to help this nation’s war effort.” - Charles F. Brannan, Farm Security Administration, Bent County Democrat May 21, 1943

The following year, however, state representative Floyd E. Cobb complained that Mexican workers made the same amount of money as American farm workers. He was immediately met with condemnation from six Latino organizations within Colorado and apologized for the comments. By 1946, Colorado still needed additional workers but had ended up on a Mexican government blacklist of eight states for treating Mexican workers unfairly. It should also be noted that throughout much of the war, incarcerated Japanese Americans and German POWs were used for farm labor in Colorado.

The Post-War Period and Operation Wetback

While the Depression was over by the 1950s, there was a small recession being experienced in the early 1950s due in part to inflation related to the Korean War. Immigrant labor again served as a convenient scapegoat for the nation’s ills. In 1953, President Eisenhower initiated Operation Wetback, which became one of the biggest mass deportation efforts in US history. It wasn't until April of 1954 that Border Patrol was able to capture their first “wetback smuggler” since the program began. Jose Cabrera was sentenced to two years in prison for bringing in labor for farms in Longmont. Many of the 1 million people deported were done so by what resembled military force. Many were treated with brutality, and more than 1,000 US citizens were also deported based on skin tone, accent, or surname. While many farmers continued to rely on migrant labor and the US had just admitted the need for these workers a few years prior, the Rocky Mountain News was now reporting on the situation hyperbolically as a “tense wetback situation” that “could explode at any time” (Rocky Mountain News October 11, 1953). The program ran out of funds and ended in 1954.

In 1957, the regional director of the US Office of Manpower Administration, John E. Gross announced that Colorado ranked sixth in Mexican labor with an estimated 8,269 farm workers for an average pay of 65 to 70 cents per hour. However, he also stated that

“Domestic workers always have had the priority for jobs, but we're having more difficulty finding enough of them.” - Rocky Mountain News March 24, 1957

The same article also points out that some 8,000 Texans also come to Colorado as seasonal farm workers. How Texan Latinos were differentiated from Mexican laborers was not specified.

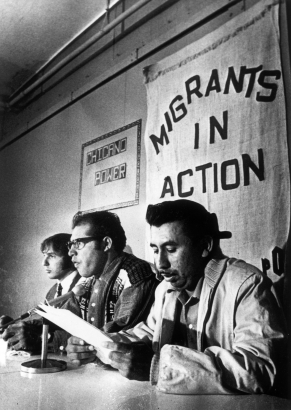

Beginning of Unionization and Attempts at Reform

In the 1960s, Colorado was again in desperate need of farm labor, particularly on sugar beet farms. Despite the need, immigration agents in Denver began arresting those suspected of being smuggled across the border to detention centers in El Paso, Texas, including 23 in September of 1961. According to the February 27, 1964 Rocky Mountain News, 12,000 of the 20,000 workers needed annually in the state were imported laborers. In response, state employment director Bernard Teets suggested bringing in African American farm labor from cotton farms in Louisiana and Mississippi.

A 1974 report produced by the Colorado Migrant Council stated that 9,000-10,000 undocumented workers were laboring in Colorado agriculture alone. More importantly, the report states that a total of up to 78,757 agricultural workers in Colorado qualified for services from the Colorado Migrant Council due to the median income of all these workers being below poverty. The 1970s were a decade that included many migrant camp closures due to unsanitary conditions, including the Fort Lupton camp and the Mizokami Brothers farm in the San Luis Valley. It was also a period in which groups like the United Farm Workers sought to unionize farm labor and demand better pay and working conditions.

A Growing Awareness of the Plight of Migrant Children

Children, which made up more than 25% of migrant workers nationwide, remained the primary victims of poor living conditions. A study of these children conducted by Dr. H. Peter Chase at University of Colorado showed,

“Twenty percent had stunted growth; 8 percent showed signs of rickets; 11 percent had impetigo; 16 percent had enlarged livers indicating overall caloric undernutrition; 39 percent had dental caries, and 9 percent were deficient in protein, 10 percent in folic acid, and 55 percent in vitamin A.” - Denver Post Empire August 7, 1977

During the 1980s, there was a growth in state and federal programs to help keep the children of migrants in school rather than working alongside their parents. In 1985, an estimated 26,000 to 34,000 migrants were coming to Colorado for work each year, with many of those in Larimer and Weld Counties. Local public schools established special programs to try and help keep children out of the fields and in schools. While the majority continued to work in the fields, one can not underestimate the impact it made in the lives of those who broke the cycle of poverty due to lack of education.

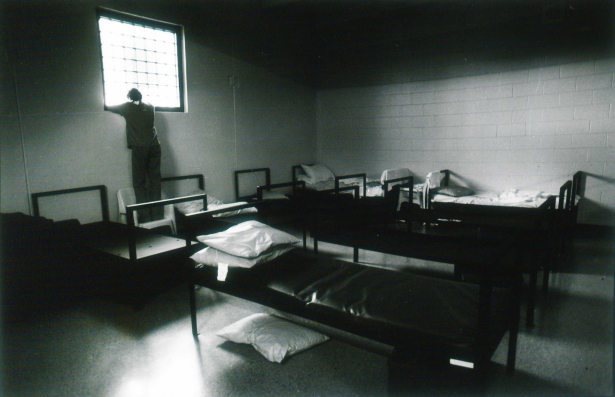

In the 1990s, federal, state, and local funds continued to help migrant children gain access to year-round schooling, but the 43,000 to 46,000 migrant workers were experiencing a new problem regarding housing. While many had lived in dangerous and substandard housing for decades, even those rural shacks were being erased or falling down. Families were beginning to move into cramped urban quarters that they could afford on wages of $75 per day. While some county housing authorities attempted to supply affordable options, groups like the Colorado Rural Housing Development Corp. (CRHDC) felt the state was failing to ameliorate the conditions of this much-needed labor pool. As a result, some of these workers began relocating to states like Washington and Oregon where investments in housing were being made. A writer at the Denver Post posed the question, “Why doesn't Colorado do more to assure decent housing for those who play a vital role in the state’s agricultural economy?”

“I guess we are spending all our money on building new prisons.” Mark Welch of CRHDC, Denver Post, August 29, 1993

History Rhymes in the 21st Century

The twenty-first century gave way to new waves of animosity against immigration on the whole. The October 23, 2006 edition of the Denver Post noted the rising importance of immigration in the upcoming election. They noted a growing call from Latino and African American religious leaders for comprehensive reforms. The Post also pointed to a growing schism amongst Evangelicals between white and Latino churchgoers.

In April 2007, ICE raided a San Luis Valley potato farm and interviewed 70 workers. This led to the arrest of 17 Mexicans and two Guatemalans. They did release two women on humanitarian grounds, which, according to the Denver Post, can include medical issues or being a sole caregiver to children. Immigrant rights groups around the states held vigils and continued the long-standing call for immigration reforms.

“This is a disturbing indictment of the nation’s priorities as many immigrant families await federal legislation that might potentially allow them to adjust their immigration status in the United States.” - Julien Ross of Colorado Immigrant Rights Coalition, Denver Post April 18, 2007

In the years that followed, there has been no consensus between the two political parties on immigration reform and farms continued to experience labor shortages. While the rhetoric around migrant laborers heated up with each successive federal campaign, the recent militarization of ICE and the Supreme Court’s temporary ruling that ICE can use race and accent as a pretext for detaining someone has changed the landscape. The fear and dangers once reserved to those largely ignored by society while they maintained our food supply has migrated into the homes of many American citizens, regardless of their race or ethnicity. Some of the most shameful chapters in our history have begun to repeat themselves.

For more information:

Colorado Migrant Council Annual Report (1974?)

Industrial relations in the beet fields of Colorado

Mexican Farm Labor and the Agricultural Economy of the United States by Mary E. Mendoza

Migrant farm labor : the problem and some efforts to meet it. 1940

Add new comment