Warning: This blog includes examples of racist language.

As far as who the first Japanese person in Colorado was, it was most likely a Harvard and Rutgers educated engineer who worked for the Union Pacific Railroad in Wyoming and became a prominent civil engineer for the city of Bradford, Pennsylvania. His name was Tadaatsu Matsudaira and he and his family relocated to Colorado for his health in 1886. They established a home on Blake Street and he worked for the Colorado State Engineer’s Office overseeing inspections on mining operations.Unfortunately, he died young in 1888, likely from tuberculosis.

No more than a handful of Issei (first generation Japanese immigrants) made it to Colorado by 1900. The real influx began in the early 20th century. Most of the railroads had been completed, but a few worked on remaining projects like a branch that extended to Steamboat Springs and Craig. Other Japanese immigrants sought mining work, but pronounced racism kept them out of many mines. Something of a war even erupted at the Chandler Mine near Florence, Colorado. The mostly Italian workforce forced out the Japanese miners and threatened them to the point where the Victor Coal and Coke Company brought in train cars to carry them out of the area. According to the company,

“We did not want to employ the Japanese. We do not like them any better than the men themselves do, but we have tried every other possible source of labor.” North Park Union February 21, 1902

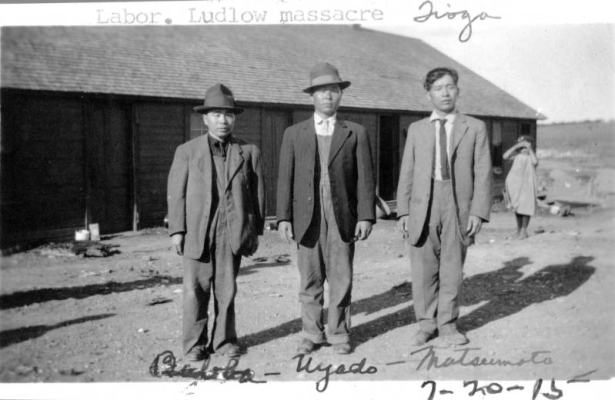

Japanese immigrants’ undesirable status led to them (along with many Mexican immigrants and migrant workers) being brought in as strikebreakers during the 1903-1904 strikes in the southern Colorado coalfields. This further alienated them from groups like the Western Federation of Miners and the United Mine Workers, who already prevented them from working in any metal mining across the state or in the northern coalfields. Despite the widespread discrimination against Japanese immigrants in the mining industry, they were among those coal miners who participated in the strike against Colorado Fuel and Iron during the infamous Ludlow Massacre.

By the time of the Ludlow Massacre, the Japanese population of Denver had grown to only 585, though Japanese business and social organizations were popping up in Denver and around the state. In 1916, the Buddhist temple was established in downtown Denver. Japanese immigrants established restaurants, hotels, and other businesses downtown, but they would find the same xenophobia that greeted Chinese immigrants decades earlier. In 1910, for example, stories ran in local papers critical of white women who married Japanese men. The police and juvenile court even banned white waitresses from working in Japanese restaurants. Similar to targeted minorities in the 21st century, the Japanese restaurants were accused of human trafficking.

“‘The Jap restaurants are the ruination of white girls,’ said an officer whose beat covers the majority of the 20 Jap restaurants in the city.” - Denver Post May 7, 1910

Unlike many other 20th century immigrant groups, Japanese immigrants did not all gravitate to the cities for work. Many came to work on or establish their own farms. Unlike many states with “alien land laws,” Colorado had no prohibitions on Japanese émigrés’ ownership of land. Japanese immigrants settled around Brighton, Rocky Ford, Grand Junction, Delta, and Weld County, among other locations. Others were victims of America’s concentration camps during World War II and stayed to farm in Colorado after the war. Many such families have become well-known across the state. There were the Tanakas in Boulder, the Noguchis of Sterling, the Tagawas of Brighton, and the Hirakatas of Rocky Ford. Lest anyone think that rural parts of the state were more welcoming, the following editorial regarding Japanese workers in the San Luis Valley would read like satire were it not so deadly serious.

“If the valley farmers and other citizens had the guts exhibited by the miners of Creede, they would have no trouble in losing this undesirable element before it lights. Creede has no foreign labor problem and never will because it’s ‘agin our principles.’ There are no macaroni stores here.” - The Creede Candle December 13, 1924

Despite the overwhelming bigotry visited upon the Issei , the Nisei and Sansei (second and third generation Japanese immigrants) became a much more accepted part of Colorado communities in the lead-up to World War II. In Fort Lupton, for example, the year 1940 would include the dedication of the Lupton Buddhist Church as well as a celebration at the Jaycee Hall in honor of the local Japanese baseball team. In Denver, there were approximately 300 Japanese American residents and a “Little Tokyo” thriving on Larimer between 18th and 23rd Streets. The following year, however, would see anti-Japanese hatred inflamed across the country, though Colorado and its governor would buck the norm.

In February 1942, President Franklin Roosevelt signed Executive Order 9066, which removed many Japanese American people from the West Coast to concentration camps established across the country. Japanese American residents were permitted to “voluntarily” relocate and many moved to Colorado where Governor Ralph Carr welcomed them and opposed the incarceration of Japanese American people. That same year, Carr had lost the US Senate race to former governor “Big Ed” Johnson who had called him a “Jap lover.” Carr did not waver.

On December 7, 1941, Daisy Osumi, who ran a jewelry store with her husband on Larimer wrote in her diary,

“Oh! What a day. Japan has declared war on us. It will sure be bad for us here in America.” - Daisy Osumi Diaries

Construction of Amache, a Japanese concentration camp near Granada, began in June 1942. By October of that same year, the population of the camp peaked at 7,567 men, women, and children. Japanese American Coloradans themselves were not incarcerated and many Coloradan Nisei served in the U.S. military during the war. Families like the Osumis worked to get those in concentration camps jobs and homes so that they could be released from places like Amache. In 1944, 22,000 of the more than 125,000 Japanese American people who had been incarcerated during the war were released from various concentration camps. Of those 22,000, 5,000 went to the Chicago area and 2,507 moved to Colorado, with 1,144 relocating to Denver. By late 1945, Denver’s Japanese population had jumped to a high of 5,000 people. The rural population jumped to over 6,000.

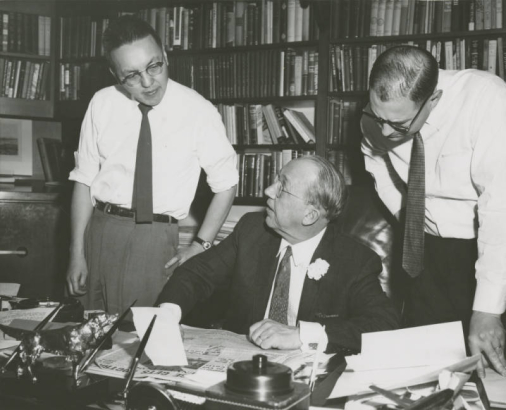

One of the new arrivals was Bill Hosokawa, a Seattle journalist who had been incarcerated with his family at Heart Mountain in Wyoming. Before Executive Order 9066, he had helped form the Japanese American Citizens League’s Emergency Defense Council to protect the rights of Japanese American people. After the war, he was looking for work and the Denver Post, which had been known for open racism against Japanese people, hired Palmer Hoyt, an editor who wanted to reform the paper. Hosokawa still had to contend with racism when he fought to buy a home in the Park Hill neighborhood, but was prolific as a writer and editor for the Denver Post, even serving as a correspondent during the Korean and Vietnam Wars. Hosokawa continued to speak out against racism and support the rights of immigrants late into his life and fought anti-Muslim bigotry after 9/11.

As the United States returned to peacetime, Japanese American people continued to establish themselves throughout Colorado communities. In 1947, Professor Frank Matsutama, friend of Jack London and master of Yawara-jutsu, a martial art, established a Denver training school for primarily police and firefighters. He ended up teaching law enforcement across the nation, including at the FBI. In 1949, Shyko Hiraga became the first Japanese American teacher in Denver Public Schools. In 1952, the McCarran-Walter Act made it easier for Japanese immigrants to become naturalized citizens. The following year, Denver held a formal ceremony in which forty Japanese American people took the oath to become U.S. citizens.

Denver has the fourth oldest group of Taiko drummers in the country. The group was started by Caroline Tagawa, Mark Miyoshi, and Joyce Nakata-Kim. Tagawa’s family settled in Colorado after her parents were incarcerated at Camp Amache. During the 1960s, San Francisco drumming master Seiji Tanaka came to Denver to help mentor the group during a workshop at Tri-State Buddhist Church. Denver Taiko was officially established as a community institution in 1976 and continues to perform to this day. In 1973, the annual Cherry Blossom Festival was established in Denver’s Sakura Square. The yearly celebration of music, food, and culture continues to draw people to Denver from around the state.

While we no longer have one of the larger Japanese populations among the U.S. states, the descendants of the early Issei and later Nisei still thrive in Colorado’s arts, agriculture, and business. Monuments have been erected to honor the earliest Japanese settlers, like Tadaatsu Matsudaira; defenders of immigrants, like Raph Carr; and to civil rights defenders, like Bill Hosokawa. The Japanese American culture persists as part of the character of our state and continues to prepare Coloradans for a diverse future together.

Further Reading:

Japanese of Colorado : a sociohistorical portrait / Russell Endo

Western History & Genealogy Clipping Files (Available upon request)

Helen and Misao Kawazoye Letter Written at Camp Amache

Comments

Thank you Alejandro, this was

Thank you Alejandro, this was an important and enjoyable read.

Thanks so much for reading,

Thanks so much for reading, Adison!

this is very interesting

this is very interesting

this is very interesting

this is very interesting

Add new comment