China has a national history going back thousands of years and remains a massive nation that takes up most of East Asia. Trade existed between Asia and Europe for at least 2,000 years, but the desire for Chinese goods and labor began to threaten Chinese independence more and more in the 19th century as the British engaged in wars over the opium trade and other powers like the United States sought to expand their trade networks and colonial outposts in the region. The presence of these Western powers also led to infighting within the Chinese government over seeking an uneasy peace with the foreigners or expelling them from the country by force. This increasing destabilization was part of the reason many sought to leave for opportunities elsewhere. Like others around the world at the time, the discovery of gold in places like California and Colorado led many to travel across the Pacific towards American shores, primarily from the Guangdong Province of China.

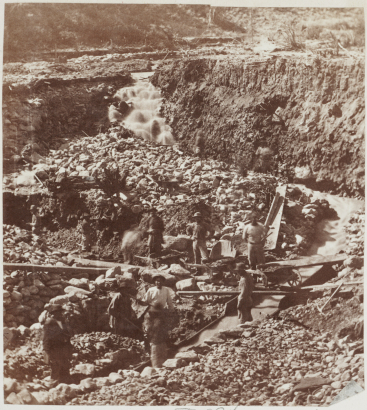

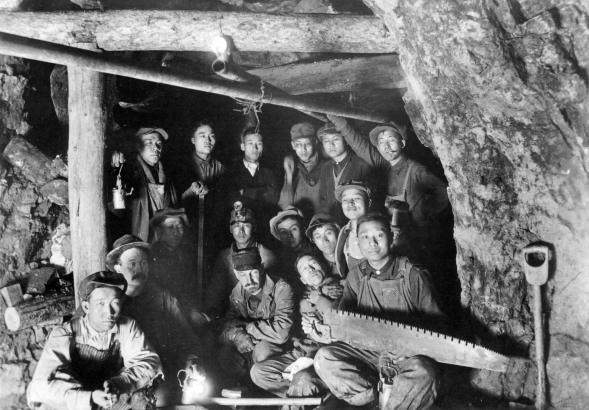

Many early Chinese immigrants ended up in places like the American South and even Cuba as replacements for enslaved Africans on plantations. While others were already working in large numbers in places like Idaho and Montana, the first report of the Chinese in Colorado was, according to historian William Wei, a man referred to simply as “John Chinaman” who appeared in Denver in June of 1869 as reported by the Colorado Tribune. A month later, the Rocky Mountain News reported the arrival of Hong Lee and said he took up a home in the Chinese quarter, which suggests there was already some established population of Chinese in Denver. Many today credit Chin Lin Sou as being among the first Chinese in Colorado. He worked many jobs building railroads across the West, eventually settling in Colorado in the 1870s to work for the Denver Pacific Railroad. By 1874, he was managing more than 300 Chinese miners and was a respected member of Central City at a time when many desired Chinese labor but hated having the Chinese in their white communities.

Considering how many of these Chinese workers lived in camps, were on the move, or were simply ignored by much of society, the best guess we have for the first Chinese residents of Colorado comes from the 1870 US census which lists seven residents who were born in China. They are Ali How, Yaa Yang, Shoe Fung, Henry Lee, Sam Lee, Wang Yong, and Whong Shang. Each one of them is listed as working in the laundry business. This was a common business for Chinese entrepreneurs at the time, and having a storefront in a town may explain why these few made it into the census. In February 1871, Denver’s Chinatown celebrated its first Chinese New Year with paper lanterns and firecrackers along Wazee Street. While many of these celebrations were reported with some affection in the newspapers, William Byers, editor of the Rocky Mountain News, launched an anti-Chinese crusade almost as soon as they arrived.

For the next decade, Byers would run regular stories from San Francisco amplifying the voice of Denis Kearney, an Irish labor leader who promoted the phrase, “The Chinese Must Go.” In March 1871, a citizens’ petition signed by over 100 Denverites was presented to the city council seeking to remove the Chinese from downtown Denver. Byers increasingly accused the Chinese of stealing the jobs of white men and corrupting society, while being unable to become true Americans due to them not being Christian. At the same time, groups like the Central Presbyterian Church were openly supportive of Chinese immigrants and their native-born children. Likewise, legislation in the Colorado General Assembly sought to ban marriage between whites, African Americans, and Chinese, but was defeated by the majority of representatives.

Unfortunately, the rhetoric in the Rocky Mountain News reached a fever pitch in late 1880. Part of this was due to an upcoming presidential election in November. People like Kearney and Byers were painting candidate James Garfield as pro-Chinese, and the News was running multiple stories per day in October about the evils of Chinese labor and their moral corruption of Denver society. This amplified prejudice led to the anti-Chinese riot on October 31, 1880 in which a mob of white citizens burned down much of Chinatown and murdered Chinese resident Look Young after beating him severely. While 1880 represented the peak of anti-Chinese sentiment in Colorado, the Rocky Mountain News also reported that year that there were only 500 total Chinese people living in the entire state. The day after the riot, the Rocky Mountain News announced in celebration, “Chinese gone!” Two years later, the US Congress passed the Chinese Exclusion Act, which severely restricted all immigration from China.

Even though many in the Chinese community in Denver decided to leave for larger cities like Chicago, people like Chin Lin Sou remained and worked to support other Chinese residents. His family lived at 2031 Market Street for years. He, and later, his sons were considered the de facto mayors of Chinatown. Many others around the state continued to work in mining. While Chinese and Italian miners had been pitted against each other in the so-called Como War in Park County, they eventually came together in the fight against the coal companies in the early 20th century. In 1914, a diverse group including Greek, Italian, Chinese, Japanese, African American, and Eastern European miners went on strike against the Colorado Fuel and Iron Company, which ended with the murder of several miners and their families. This was a major turning point in the union movement of miners fighting for fair pay and better working conditions.

Despite generations living and working in Colorado, the Chinese Exclusion Act continued to erode the diversity of Colorado. The once vibrant Chinese community in Denver had dwindled to 110 people in 1940. That same year, much of the infamous “Hop Alley” was torn down. Historian William Wei states that the majority of the remaining Chinese Americans belonged to a small number of families like the Fongs, Looks, and Chins. Roger Fong, born and raised in Denver, was spotlighted in the October 23, 1941 issue of the Rocky Mountain News for being one of a small number of Chinese Americans enlisted in the Army. He would serve as a Sergeant in the 42nd Engineers Regiment. Edward Chin, grandson of Chin Lin Sou, was also covered by the News for his service in World War II. By 1951, many of the turn-of-the-century buildings in Chinatown and the larger Lower Downtown were falling apart and being torn down, then replaced with warehouses and trucking offices. That year, Jimmy Chin was living in one such building that housed himself and several other elderly residents who remained in the Chinatown they had grown up in.

While the Chinese Exclusion Acts officially ended in 1943, strict quotas on the Chinese were not removed until 1965. The following year, China’s Communist Party Chairman Mao Zedong began the massive upheaval known as the Cultural Revolution, which led to many Chinese citizens immigrating to nations like the US. This led to a very different generation of Chinese Americans who had grown up in a very different China. One of the first of this generation in Colorado was Joe Luk, who left for America at age 18, attended college at the University of Nebraska, and moved to Colorado, where he opened Tao Tao restaurants in Boulder and Colorado Springs. He hoped to bring more traditional Cantonese dishes to Colorado.

“Americans have travelled in Korea, Vietnam, and Hong Kong and are more familiar with Chinese cuisine than they have been in the past. They come back to the United States and have a dish that they had overseas so now the Chinese restaurant business is being forced to become more authentic.” - Colorado Daily (University of Colorado, Boulder), May 8, 1974

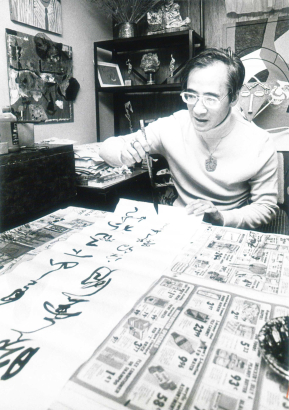

Sheng-Piao Kiang came to Colorado for university during the Chinese Civil War in the 1940s. When the communists took over China in 1949, he decided to stay and devote himself to creating and teaching art. He embraced sculpture, painting, and calligraphy and found interesting ways to merge Chinese and European art styles with American objects like Midwestern corn and sunflowers. He would spend decades teaching art to aspiring students. Other Chinese immigrants like Tommy Wong and John Locke worked through the Denver chapter of the national Hip Sing organization to help new arrivals learn English and find jobs. Their 1984 Chinese New Year celebration at Wong’s restaurant brought in a crowd of 500 people, including Denver Mayor Federico Peña.

In 1989, a massive student protest took place in Tiananmen Square in Beijing to bring about democratic reforms. Many students were killed by the government, and some of the student leaders ended up in the United States. One such leader, Yin Ping Zhang, ended up in hiding in Manitou Springs, Colorado. She hoped to attend medical school in Colorado, but not much is known about her after she went into hiding.

There is no doubt that the Chinese contributed greatly to the state of Colorado despite facing adversities and bigotry from all quarters. In 2022, cousins Linda Jew and Linda Lung were present for the formal apology by the city of Denver for the anti-Chinese riot of 1880. They are some of the descendants of the original residents of Denver’s Chinatown. While the struggles both in China and in the United States punctuate the Chinese-American experience, they have over time gained more respect and recognition in the many communities they enrich. Tensions between the US and China continue to fuel racist reactions toward Chinese Americans, but one can no longer doubt that this community is now an integral part of the American story and a source of strength going forward.

More Resources:

Asians in Colorado : a history of persecution and perseverance in the Centennial State / William Wei

The road to Chinese exclusion : the Denver riot, 1880 election, and rise of the West / Liping Zhu

Chin Lin Sou : Chinese-American leader / by Janet L. Taggart

Immigration from China (Library of Congress)

China’s Lost Women in the Far West by Lynne Yuan

The Forgotten History of the Purging of the Chinese from America

![A Chinese man poses on a wooden sidewalk near a business district possibly in Colorado. A nearby sign on a building reads: "[?]ng Lee [La]undry".](/sites/history/files/styles/blog_image/public/recollect_1037621.jpg?itok=LH76JArY)