When dawn broke over Denver on December 1, 1913, almost no one knew that they were squarely in the jaws of the worst snowstorm the city had ever seen. Over the course of the next five days, the Blizzard of 1913 would dump 45.7 inches of wet, heavy snow on a city that was completely unprepared for the icy onslaught.

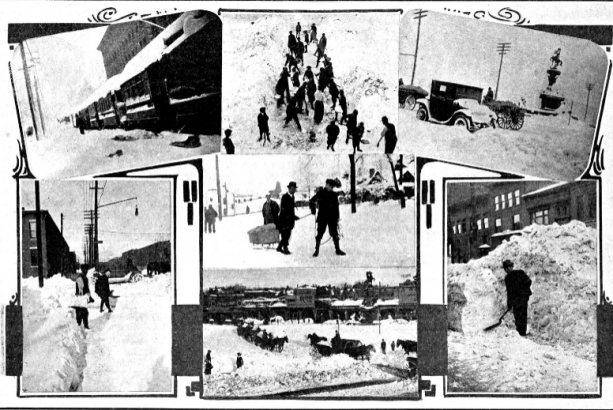

Though Denver was caught flat-footed, its citizens and city government bounced back with a clean-up effort that started on December 1 and continued for a full month. When it was finished, literally billions of pounds of snow had been removed and the Mile High City emerged relatively unscathed.

The Calm (and Cold) Before the Storm

The fall and winter of 1913 were somewhat unusual from the get-go. Denver had experienced its first measurable snow of the season on September 11. According to the National Weather Service, the average first snowfall in Denver occurs around October 18, and the earliest snowfall was recorded in 1964 when flurries came down on September 3. Though the first part of the cold season was unusually brisk and snowy, November 1913 was extremely dry and warm.

That warming trend was actually still in effect when the first flakes of the big storm started falling on December 1, and the temperature hovered at around 32 degrees. All that warm air created a wet, heavy snow that felt more like a spring snow than the dry, powdery snow that normally falls in fall and winter. And, as we'll see, it created a major issue for desperate Denverites who shoveled with intensity as they hoped to stay ahead of collapsing roofs.

For the first couple of days, the storm wasn't all that bad. On Monday, December 1, 4.2 inches dropped, followed by 1.4 inches on Tuesday and 2.4 inches on Wednesday. It was a lot of snow but nothing that couldn't be managed. Most importantly, the Denver streetcar system remained operational, though the Denver Tramway Company threw every available piece of snow removal equipment it had at rapidly accumulating snow. The company also hired hundreds of laborers to manually remove snow from its lines.

Sensing that the unexpected snowfall was going to get worse, Mayor J.M. Perkins called on the citizens of Denver to keep the sidewalks clear and to help out city workers as much as possible. But it was a losing battle because, by Thursday, December 4, the Blizzard of 1913 was just getting started.

The Worst is Yet to Come

According to a report in Denver Municipal Facts, Denver's entire streetcar system was stopped, literally, in its tracks by Thursday afternoon. That's not so surprising given the fact that more than 20 inches of snow fell that day. But hundreds of downtown workers (mostly men, as women workers were sent home early that day) found themselves stranded in the snowbound city. These marooned men stuffed themselves into every available hotel and rooming house in the city. Several auditoriums and local department stores were called on to open their doors to the overflow.

By all accounts, the atmosphere remained mostly positive. Denver Municipal Facts reported that no arrests occurred at any of makeshift shelters and that a jovial, party atmosphere ruled the day.

During the storm, the army of hired laborers employed in removing the ever-growing piles of snow had swelled to nearly 4,000. This mini job boom put cash in the pockets of many low-income workers and reduced demand from local charities for food assistance.

Fortunately, Denver's other utilities, including phone systems, the electrical grid, and the water system worked without major problems. Finding an open phone line during the storm was difficult as thousands of stranded Denverites phoned home or searched for loved ones who hadn't returned from work.

Denver Digs Out

By Saturday, the precipitation had stopped and Denverites found themselves encased in snow and ice. Snowbound trains piled up at Union Station and streetcars remained trapped by deep drifts. Even in areas where drifts had not accumulated, the snow was more than four feet deep.

City employees took to horseback to make emergency coal deliveries to households that were running low on the precious material. Coal was in short supply that winter due to a coal miner strike in southern Colorado. But overall, things weren't that bad...except for the snow.

Throughout the storm, Mayor Perkins had deployed entire city agencies, including the Sanitation Department, all available street cleaners, and highway workers as snow removal teams. Much of the accumulated snow was shoveled into wagons and dumped at Civic Center Park. But the amount of snow they were dealing with was truly staggering.

According to Municipal Facts, workers removed roughly six billion cubic feet of snow, which weighed in at around 35 billion pounds. They estimated that all that snow would have filled approximately 880,000 rail cars. It wasn't until December 31 that City leaders declared the storm's clean-up complete.

We Could Sure Use the Moisture

People in Colorado are fond of saying, "We could sure use the moisture," each time it rains or snows — and that's probably because of how true that statement happens to be. While we're not certain that anyone used that phrase in 1913, it was definitely accurate that year. After a very dry fall, the December snowfall dropped huge amounts of moisture into Colorado's parched soil. All that water provided extra nourishment to the 1914 harvest, which turned out to be one of the best on record.

But the snow's impact wasn't just felt at the local market. Because so many buildings collapsed under the weight of moisture-heavy snow, Denver and other municipalities required new builds to be able to bear greater amounts of weight than they had in past times. Many of those building codes are still on the books today.

Though Denver prepared to face another massive storm, nothing like the Blizzard of 1913 has happened since. The next biggest storm occurred in March 2003, when 31.8 inches dropped on Denver — and that storm made the 23.8 inches from the Christmas Eve Blizzard of 1982 seem like nothing.

While it's possible that another 45-inch snowfall is waiting in the unwritten future, it's unlikely that Denver will experience anything like the Blizzard of 1913 again.

Add new comment