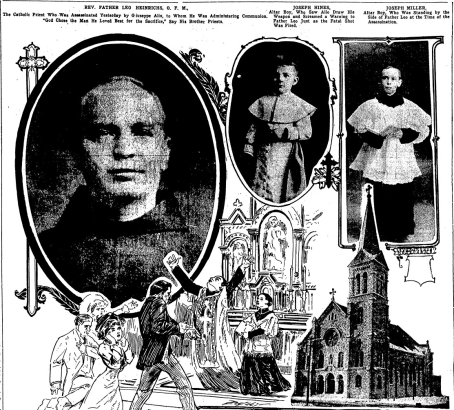

In the early morning of February 23, 1908, parishioners gathered at the Church of St. Elizabeth, which now stands on the Auraria Campus. At about 6:30 a.m., Franciscan Priest Father Leo Heinrichs finished consecrating the host while attendees approached the altar and kneeled at the railing.

Amongst those awaiting communion was a Sicilian anarchist named Giuseppe Alia. A moment after Father Leo placed the host on Alia’s tongue, Alia pulled out a revolver. An altar boy called out to the priest, but in an instant, a bullet was fired into Father Heinrichs’ chest. According to the account in the next day’s Denver Post, Heinrichs tried to put down the ciborium holding the remaining hosts to prevent them from touching the ground, but almost immediately fell to the ground himself, dead from a severed aorta.

Father Heinrich’s last words were, “Call Father Eusebius.” Eusebius was immediately summoned to take charge of the remaining congregants. As Alia attempted to flee the church, he was followed out by Daniel Cronin, a Denver police officer. Cronin wrested the gun from Alia and brought him to the police station. Local authorities wisely removed the assassin from Denver to Colorado Springs in order to avoid mob violence. Only 15 years earlier, another Italian had been broken out of the jail and lynched by a mob of thousands. Southern and Eastern Europeans were already looked upon with suspicion and the murder of a priest would only serve to ignite those pre-existing prejudices.

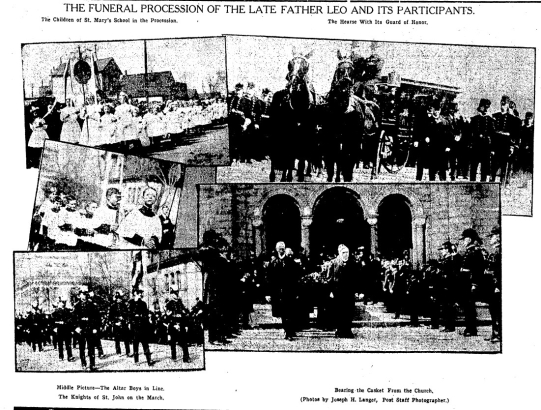

Bishop Matz ordered the diocese to reconsecrate the church, as was customary when a crime of violence had taken place in a house of worship. A requiem was planned by Heinrichs’ fellow monks, local Catholic clergy, and the Knights of Columbus. Seats were reserved for the governor, the mayor, and other dignitaries and community leaders. Father Heinrichs, now considered a martyr to the faith, would eventually be put forth as a candidate for sainthood. In the meantime, the already heightened fear of anarchists exploded across this country as well as Europe.

After the invention of dynamite in the 1860s by Alfred Nobel, the concept of “bomb-throwers” became much more of a real threat. In the 1880s, the politics of communists, anarchists, labor activists, anti-monarchists, anticlericals, and the like grew in their potential for violent action. This was certainly punctuated by the assassination of President William McKinley in 1901 by anarchist Leon Czolgosz. That is not to say that all adherents of these movements were inherently violent, but, like after 9/11, a broad swath of people were painted with an even broader brush of contempt and distrust.

As a result, in 1903, the United States passed what came to be known as the Anarchist Exclusion Act. It banned anyone coming into the country who maintained “disbelief in or opposition to all organized government.” Prominent American anarchist Emma Goldman was banned from speaking in public by the Chicago Police, and Denver labor leaders appeared pressured to renounce anarchists. At the time, and through the Red Scare to come, all such groups mentioned prior were often referred to simply as “reds.”

Besides political affiliations, the climate continued to grow hostile to immigrants from Southern and Eastern Europe. According to the March 6, 1908, Denver Post, people were even becoming hostile to Italian nuns. The Missionary Society of the Sacred Heart would often go through the neighborhood, asking residents for alms. After the murder, the nuns were turned away. The order claimed that one nun, Sister Anastasia, was struck dead by a broken heart after being denied aid and told, “An Italian has killed a priest.” It should be noted that the official cause of death was pneumonia, but prejudice was certainly on the rise against various ethnic groups. Such momentum continued to build and become more explicit with the rise of the Ku Klux Klan and the Red Scare in the 1920s.

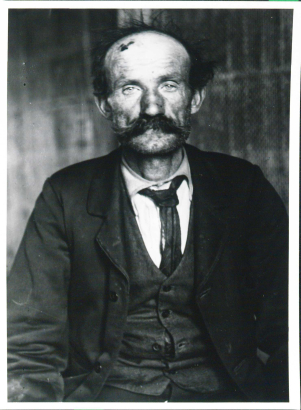

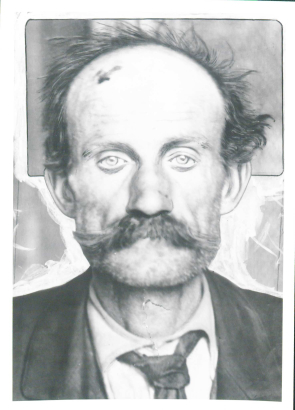

As tensions rose across the country, having Father Heinrichs’ assassin in custody did little to clarify the full scope of the plot. At first, Alia claimed that, back in Sicily, his wife had left him after being denounced for his anarchism by a priest he thought to have been Heinrichs. When Alia was told Heinrichs had never been to Italy, he began screaming about having killed the wrong man and told a somewhat different story of what happened in Italy. Alia claimed to have been part of a violent Easter protest in Avola, Italy, 12 years prior, to have been decried by the community, and to have fled eventually to Buenos Aires, Argentina, where other members of his small cohort had already gone. Supposedly, the group in Buenos Aires then sent him to New York in order to track down and kill the priest that had targeted anarchists and socialists back in Sicily.

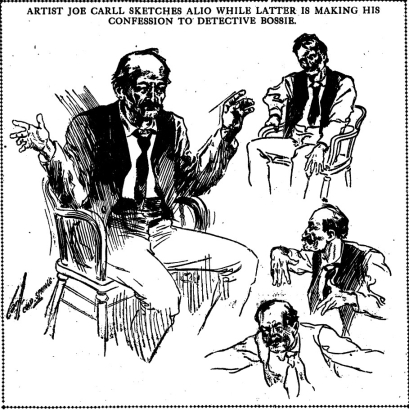

Alia further claimed that, by the time he reached Denver he had largely lost any sense of mission, but his anger was inflamed on the morning of February 23, 1908, after hearing the church bells ringing. While deeply upset about killing the wrong priest, he said he felt no guilt about having murdered a priest more generally. Importantly, he said he was not part of any group since reaching Denver. This is relevant since law enforcement across the country was trying to tie him to violent plots in places as far-flung as Wakefield, Massachusetts, and Chicago, Illinois. An interview with Alia covered in the February 28, 1908, Rocky Mountain News, conveyed yet a new story from the man facing trial for murder.

Alia’s new claim was that the previous confession to Detective Claude Bossie never happened, that he was a good Catholic, and that he never killed the priest. He then claimed that he only ran from the church because everyone else jumped up. Alia admitted to having spit out the Eucharist only because he had not taken confession beforehand. His defense attorney also decided to plead his innocence on the basis of insanity and requested intercession from the Italian consulate.

Baron G. Tosti, the Italian consul to Denver, met with Alia and told others that if the man was sane, he should hang, but also that,

“I am somewhat of a student of mental disorders myself and I feel that Alia’s mind is not quite clear.” Rocky Mountain News February 29, 1908

A few days later, four physicians were brought in to assess Alia’s sanity and were unanimous in declaring that he was sane. The Italian consul also accepted this ruling by the experts. On Monday, March 9, 1908, the trial began in the West Side Court at Kalamath and 14th Avenue in Denver. Hundreds of angry onlookers watched his procession from the jail to the courthouse.

The jurors were all men, none were Catholic, and, perhaps surprisingly for the time, many did not have a church affiliation. The newspapers published the jurors' photos, brief biographies, and home addresses. The trial included experts testifying to Alia’s sanity, altar boys reenacting the murder, and other witness testimony by parishioners.

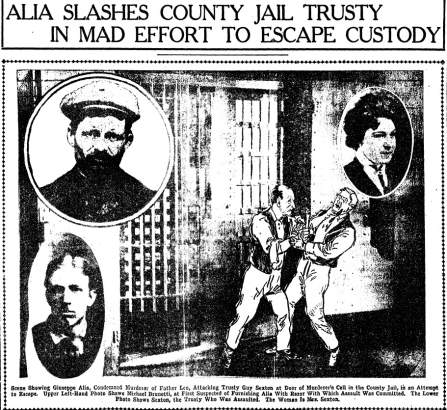

On March 12, the jury returned a guilty verdict. Two days later, Alia slashed the neck of a county jail trustee with a straight razor in a failed escape attempt. His cellmate, Michael Brunetti, was accused of providing Alia with the razor, and rumors began to fly regarding a larger organized plot by “reds.” Five days later, the jail accused Alia of being in possession of a blade removed from a pair of scissors. That same day, Alia’s lawyer filed a motion for a new trial.

On March 21, the judge denied the motion for a new trial and delivered a sentence of death by hanging. Upon hearing this, Alia began wailing and pounding his head on the floor. He was removed to the prison in Cañon City, where he would await execution for 16 weeks in a solitary confinement room adjoining the gallows. Alia was not told the day of his execution until that morning, July 15th. According to the Denver Post, he ate his last meal after several readings of a letter from his wife and two of his children. The meal was divided into five servings so he could eat, “with wife and babies.” Soon after, he was taken to the gallows room, hanged, and buried in a pine box in the prison cemetery. No hard evidence of Alia’s participation in an organized, national anarchist plot was ever presented.

Comments

You were telling me about

You were telling me about this. What an interesting story from beginning to end! Thanks for sharing it.

Glad you enjoyed it! Denver

Glad you enjoyed it! Denver is full of truly weird history.

please see my article in …

please see my article in Fearless Before the Lord: Giuseppe Alia and Religious and Political Radicalism" in "Journal for the Study of Radicalism", vol. 13, number 2, fall 2019, pp. 45-63

Thank you, Michele. If I can…

Thank you, Michele. A colleague was able to get me access to your article. I will add it to the file we have on Alia. I found the background information regarding Pachino and the Waldensians particularly fascinating.

What an intriguing story! I

What an intriguing story! I was totally unaware of this person and his crime. Thanks for writing it up.

Thanks so much, Cori! I too

Thanks so much, Cori! I too was shocked when my colleague, Laura, came across this story.

Why was the last sentence

Why was the last sentence necessary? A qualifier to reduce the gravity of the murder?

Rich, I don't see how the

Rich, I don't see how the statement minimized the crime. It serves to show that much of the panic surrounding a national plot was, as so often happens, unfounded. Police in Chicago, for example, were talking about arming priests at the time. Thanks for reading.

Fr Leo Heinrichs served as a

Fr Leo Heinrichs served as a visiting priest for a year or so in the 1890s in my parish of St Marys in Far Rockaway, Queens NY.

Sean, that would make sense

Sean, that would make sense since he had only arrrived in Denver from New York in 1907. Thanks so much for reading.

Add new comment