Not far from today's Denver Central Library, across Civic Center Park at the corner of 15th Street and Cleveland Place, there once existed a large theater known alternately as the Metropolitan Theatre, 15th Street Theatre and finally the People’s Theatre. Though short-lived, the Metropolitan Theatre was located in what was known as the “uptown” or the eastern most edge of the central Denver business district. The surrounding neighborhoods were primarily residential and mixed use.

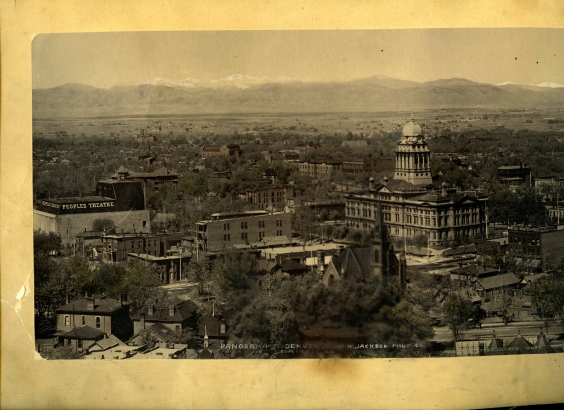

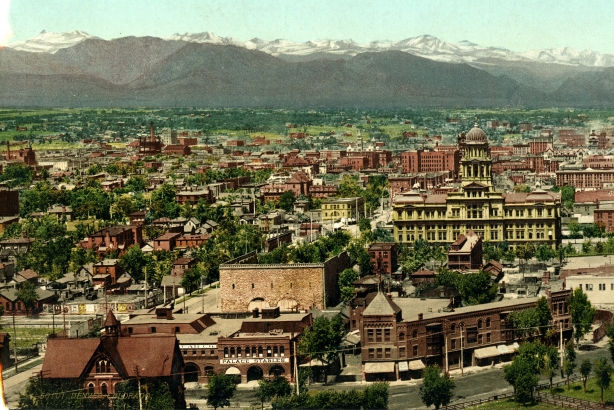

The roof and fly space of the People’s (Metropolitan) Theatre can be seen on the far left hand side of the above photograph. This photo was probably taken from the Steeple (Tower) of the Central Presbyterian Church located at Sherman Street and East 17th Avenue. It is the only known photograph of the theater while it was in operation.

Construction

Construction of the Metropolitan Theatre began in the spring of 1889. It was built by C. M. Fagen-Busch, the owner of a stone quarry. Approximately $95,000 (roughly $2.8 million today) was supplied by William Lockhardt Smith and several other investors from Philadelphia. Unfortunately, the theater operated for less than three years and its operation was marked by constant renovations, changes in ownership and lawsuits arising out of financial difficulties.

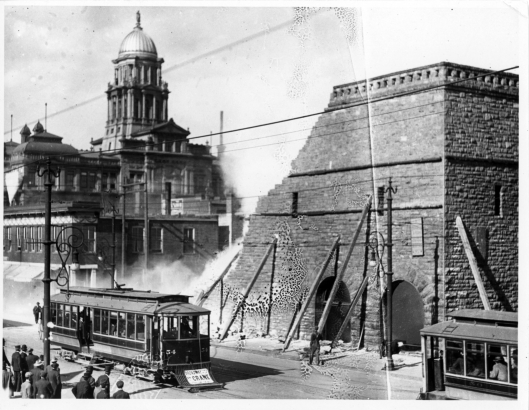

The building was constructed of white sandstone and measured 100 x 125 feet and was over three stories high. The main entrance, consisting of two twenty-four foot arches, was on Cleveland Place. Access to the gallery (2nd balcony) was through a ten-foot arch located on 15th Street. The above image clearly shows the burned out remains of the People’s Theatre. The front façade on Cleveland Place is characterized by two 24-foot high entrance arches. The image below shows the entrance to gallery seating located on 15th Street.

The Interior

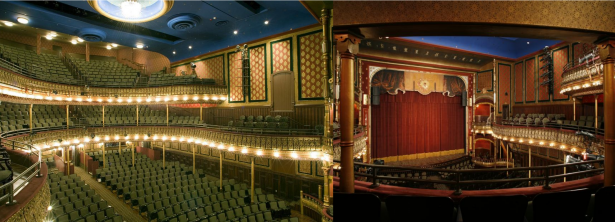

The stage, largest in the city at the time, was 100 feet wide by 45 feet deep. There were also 16 dressing rooms located under the stage. Seating in the theater numbered 2,384 (1000 more than the Tabor Opera House) and was configured on three levels: orchestra, balcony with a row of loge boxes, and the gallery. As was common for theaters of the era, some boxes were located next to the proscenium.

The above cross-section of the theater shows its interior layout. The stage and dressing rooms at the theater were located seven feet below street level. This arrangement allowed for easier access by patrons to the orchestra/main floor seating. Patrons could conveniently walk straight from the lobby into the orchestra section without first having to go up a set of stairs.

Newspapers at the time declared, “the architect who planned the structure had in his mind’s eye the most magnificent palace of amusement in the world… the new theater was constructed after the model of La Scala of Milan [and]… Denver’s new play house is wider than it is deep.” (Daily News Supplement, August 30, 1889, page 9).

Though we do not have any photographs of the Metropolitan Theatre interior, we can extrapolate what it might have looked like from similar theaters of the era. Mississippi State University’s Riley Center (Grand Opera House), located in Meridian, Mississippi, opened on December 17, 1890, and approximates the seating configuration, interior decoration, and general arrangement of the Metropolitan.

Operation

The Metropolitan Theatre opened to much fanfare on September 23, 1889 with King Cole II, a comic opera in 2 acts by Woolson Morse; lyrics by J. Cheever Goodwin. Despite its initial success, over the ensuing months attendance dropped off and the theater was threatened with liens and attachments and eventually closed. Much of this was due to the building not being completely finished at opening and, during a particularly cold fall and winter, it was hard to keep the theater warm and comfortable enough for the audience.

After some updates and repairs, the theater was renamed the 15th Street Theatre and reopened on January 10, 1890 with Mrs. George Knight in Over the Garden Wall. On Saturday, February 28, 1890, world-famous opera singer Adelina Patti (1843-1919) performed at the theater with the Royal Italian Opera Company in Martha.

Later that spring, H.A.W. Tabor leased the theater, eventually purchasing it in July 1890. Problems continued and the theater closed for extensive repairs. After the installation of steam heating, a new lighting system and other refurbishments totaling $5000, the 15th Street Theatre reopened on Monday, October 13, 1890 with Albert Salvini in A Child of Naples.

Yet, competition in the form of a new theater had arisen when the Broadway Theatre opened on August 18, 1890. The Broadway Theater was located across from the Brown Palace Hotel, at 1756 Broadway, and accessible through the Metropole Hotel. Although the 15th Street Theatre continued to be successful at presenting road shows and other entertainment, the competition from both the Broadway Theater and the Tabor Opera House cut into the theater’s business. By late summer 1891, the 15th Street Theatre was leased to J. A. Dixon and rechristened the People’s Theatre.

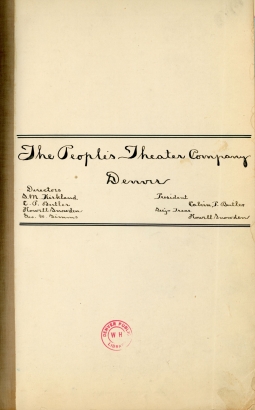

The theater was almost immediately then leased for five years to the the Wessells & Samm Stock Company on September 30, 1891. A stock company is a repertory company usually based in a single theater. The People's Theater Company was directed by George W. Wessells and his wife, Mildred N. Hall . The couple were both well-respected touring actors and the aunt and uncle of Antoinette Perry. From the middle of August 1891 to the following June, the People’s Theatre Company presented an almost uninterrupted season of favorite stock pieces.

Western History and Genealogy holds the account book for the People's Theater's last year of operation, detailing names of plays performed, attendance, receipts and disbursements for the stock company's performances. The account book covers the theater right up to its final performance.

Fire and Fate

After a performance by the People’s Theater Company on June 10, 1892, a fire broke out in the theater sometime after midnight. Within ten minutes the fire department arrived and were pouring four streams of water on the flames. Yet so much wood had been used in the construction of the building that the fire spread rapidly and only the stone walls were left standing by 12:30 a.m. With the burning of the People’s Theatre, Denver was left without an adequate stock company. The shell of the People’s Theatre can be seen in the photo above, with smoke still rising from the interior of the remains of the building.

H.A.W. Tabor, who carried $25,000 worth of insurance on the building, estimated the loss at $40,000. The scenery, consisting of forty full sets, was owned by Wessells & Samms, who carried no insurance. They estimated their losses for scenery and manuscripts at $15,000.

The fact that the walls of the theater remained standing after the fire proved an annoyance to the city. Tabor made no attempt to demolish them and even intimated that he might erect a new theater. After Tabor’s subsequent financial problems and death, the future of the walls of the theater remained in limbo for another 18 years until finally being taken down in 1910.

Timing is everything. Even though the Metropolitan Theatre began with high expectations, problems with management, the building and its construction eventually limited its ability to prosper. After finally resolving these problems and establishing a functioning theater with a stock company in residence, a fire broke out and sealed the fate for the theater forever.

Information for this blog post was largely derived from Colorado theatres, 1859-1859 by Benjamin Draper, A history of the Denver theatre during the post-pioneer period (1881-1901) by William Campton Bell and WHG clippings files for Denver Theaters.

~Posted on Behalf of Archivist/Librarian Martin Leuthauser~

Comments

Amazing article! We are

Amazing article! We are related to Harry Samm, of Wessels & Samm. Additionally the was manager of the Lyceum theater in Leadville! So glad this article was done and done well. Thank you!

BrittanySamm@outlook.com

Very cool, and thank you for

Very cool, and thank you for the additional information on Harry Samm. Glad you enjoyed the article.

What all was built after the

What all was built after the walls came down?

Good question, Judith! From

Good question, Judith! From Martin (the author of this fine piece):

The line about the competing

The line about the competing Broadway Theater makes me interested in hearing more about that theater. Can you do another blog about the Broadway Theater and what was built after, since it's not around anymore?

Thanks for letting us know,

Thanks for letting us know, Auggie! I'll talk to Martin and see if we can get a Broadway blog post underway. Glad you're interested.

We are related to Harry Samm…

We are related to Harry Samm, of Wessels & Samm. Additionally the was manager of the Lyceum theater in Leadville! So glad this article was done and done well. Thank you!

<a href="https://www.arktheatre.org/">ARK Theatre</a>

Add new comment