When Duke Ellington played the Casino Ballroom in 1936, his band was too large for the stage, so they set up on the floor and played late into the night. This is just one example of the many musicians that entertained Denverites for decades in the Five Points neighborhood, also known as the “Harlem of the West.”

Located north of Downtown Denver, Five Points was home to more than 90 percent of Denver’s African American population by 1920. A mix of development, growth, and new modes of transportation throughout Denver neighborhoods, in conjunction with segregation, influenced the demographics of Five Points. While outright segregation was against the law in Colorado, few white-owned businesses adhered. There may not have been “whites only” signs in the windows, but it was understood that Black people would not be served at many establishments. This meant Black musicians could not stay in the neighborhoods and hotels where they performed, so most not only stayed in Five Points but also played additional shows there.

With the rise of touring musicians throughout the country and Black entertainers among those, venues and hotels in Five Points started to pop up. Many of these establishments were located on Welton Street which was referred to as the “Welton Strip.”

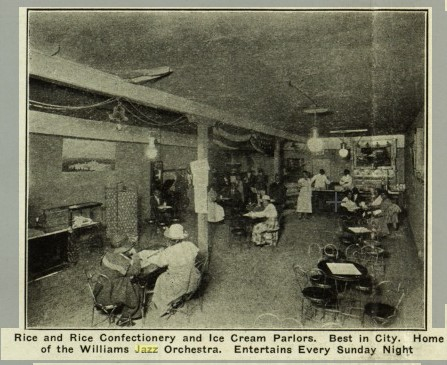

Live jazz music in Five Points started early and within unexpected venues like the Rice and Rice Confectionery and Ice Cream Parlor. Located at 2735 Welton, the ice cream parlor was one of the first businesses to hold live music, including the local Williams Jazz Orchestra which played every Sunday night.

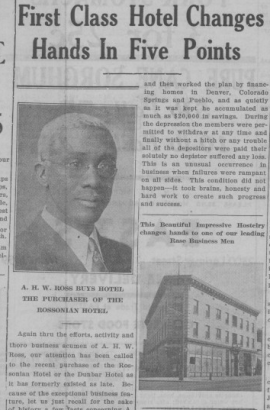

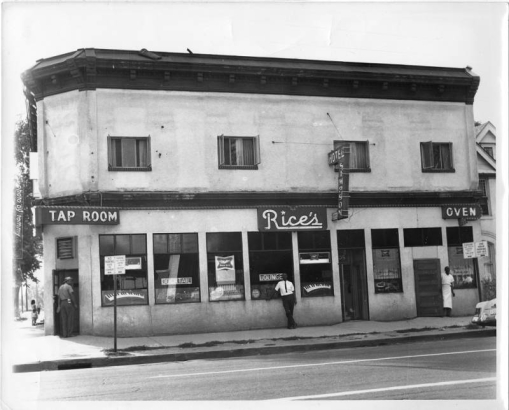

The Rossonian was the most notable venue on the strip at 2642 Welton Street. Built in 1912, the building was sold in 1929 to Alfred H.W. Ross, for whom its named, and ten other partners of the Metropolitan Real Estate and Investment Company. The Rossonian was a sleek hotel with a lounge. Nationally known figures performed at the Rossonian, including Duke Ellington, Ella Fitzgerald, and Billie Holiday. When folks wanted to listen to music, they went to the Rossonian; when they wanted to dance, they crossed Welton Street to the Casino Ballroom.

Owned by Ben Hooper, the Casino Ballroom could handle big crowds with its large dance floor and 40-foot bar. After returning home from World War II, and before opening the Casino Ballroom, Hooper ran the Ex-Servicemen's Club next door where he hosted concerts in the club’s basement. Affectionately known as “The Hole,” the club laid the foundation for many local jazzmen by pairing them with well-known traveling musicians in the famous Sunday night jam fests.

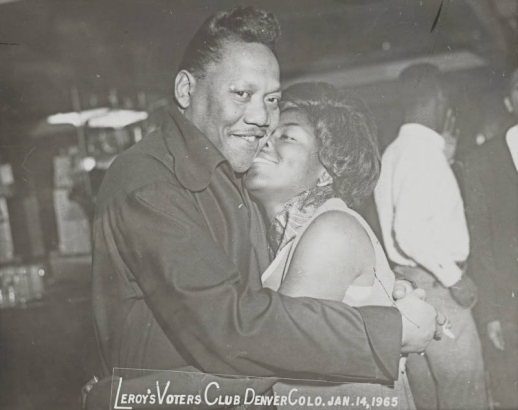

The Voter’s Club, at 2617 Welton Street was a nightclub next to Rhythm Records and both were run by Leroy Smith. The club hosted live music and prominent guests, but it was also where Smith would rally Blacks to vote in Denver, hence the club’s unique name.

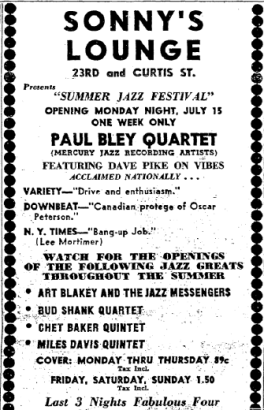

Sonny’s Lounge was not on the Welton strip, but at 23rd and Curtis it stood out as a big contender in the jazz club arena. In 1957, Sonny’s held the “Summer Jazz Festival” and brought in some of the biggest names for an entire week, including the “prince of cool” trumpeter Chet Baker and Miles Davis.

Outside of the Five Points neighborhood, other dancehalls including the Lakeside Ballroom and the Elitch Gardens Trocadero Ballroom attracted musicians too. But few rivaled the Rainbow Ballroom. Located just outside of Five Points on 5th and Lincoln, the Rainbow Ballroom had the largest dance floor west of the Mississippi. Leroy Smith was responsible for booking some of the biggest names in music at the time, including Count Basie, Lester Young, and Dizzy Gillespie.

Despite having the largest dance floor, the Rainbow Ballroom did not allow interracial dancing. An article featured in The Crisis, titled “Racial Situation in Denver,” explains:

When Negro orchestras visit the city, the Rainbow Ball Room is rented to the Negroes who serve as their sponsors. White patrons may attend as spectators, but must not dance…This is a stipulation in the contract of rental and is enforced by the police…Elitch Gardens, Denver’s leading place of entertainment, will admit Negroes, but they are not permitted to dance.

This was a stark difference from the clubs located in Five Points, which welcomed everyone to the dance floor. Just as white folks in New York traveled uptown to Harlem to dance, white Denverites went to Five Points for the best music and dancing.

Fast forward to the jazz scene in Denver today and you will still find a few niche spots where the community is as vibrant as it was 70 years ago. Though outside of Five Points, Dazzle and the Nocturne Jazz and Supper Club are the new staples, and the annual Five Points Jazz Fest draws in over 100,000 people a year.

Stay tuned for part two where we will explore the jazz musicians that launched their careers in Denver and Five Points. If you are interested in learning more, come visit the Western History reading room at the Central Library during regular business hours or check out the resources below. Note that the manuscript collections used for this blog are usually held at the Blair Caldwell African American Research Library, but due to construction, they are being held at the Central Library location until 2023.

Reference List:

- Colorado Historic Newspapers

- Colorado Statesman microfilm

- Denver Post Microfilm

- Digital Collections

- Goodstein, Phil. Curtis Park, Five Points, and beyond: the heart of historic East Denver

- Leroy Smith Papers

- Rocky Mountain News Microfilm

- Watkins, Mark Hanna. “Racial Situation in Denver.” The Crisis v. 52, no. 5 (May 1945): 139-140.

Comments

Great article! The picture of

Great article! The picture of the Rainbow Ballroom really sets the scene, and it is a lively one!

Add new comment