With recent developments concerning the novel coronavirus (Covid-19), the 1918 Flu Pandemic has popped up in articles and conversations. Why is a 102-year-old influenza pandemic on people's minds?

Read on to discover what lessons (and perspective) Denver's response to past flu outbreaks can provide in 2020.

LOOKING BACK AT 1968 & 1976

By late winter 1976, Colorado was experiencing its worst flu season since 1968.

Back in 1968, a virus known as Influenza A Subtype H3N2—later named "Hong Kong flu"—was responsible for the third influenza pandemic of the 20th century (just after 1918 and 1957). In Colorado, 50,317 cases and 955 deaths were counted by the end of 1968.

On March 12, 1976, the Denver Post revealed 24,183 cases of flu had been reported in Colorado. The death toll had reached 44 persons.

Sure, these weren't 1968 pandemic figures, but it was clear that the new A2 Victoria flu strain outbreak was severe.

For F. David Matthews, U.S. Secretary of Health, Education and Welfare, the real worry in 1976 was not A2 Victoria flu, but rather Swine flu (Influenza A Virus Subtype H1N1), which had killed a young soldier at Fort Dix, New Jersey, in February.

On March 15, 1976, Matthews wrote an ominous memo to James Thomas Lynn at the Office of Management and Budget:

There is evidence there will be a major flu epidemic this coming fall.

The indication is that we will see a return of the 1918 flu virus that is the most virulent form of flu. In 1918 a half million people died. The projections are that this virus will kill one million Americans in 1976.

[Spoiler alert: emergency legislation for the National Swine Flu Immunization Program was signed on April 15, 1976. The program, which aspired to vaccinate 80% Americans in a short period of time, encountered problems, many relating to the use of live virus vaccines, which caused adverse side effects in some individuals.]

1918 FLU PANDEMIC

Matthews' comparison of the 1976 Swine flu to 1918 Spanish flu—which is believed to have killed between 50 and 100 million people worldwide (670,000 in the U.S. alone)—was worrisome.

Between September 1918 and June 1919, 7,783 Coloradans died from influenza and its complications. Denver, with a population of around 250,000 at the time, was hit badly. Roughly 586 people per 100,000 died in the city, despite movement restrictions intended to stop the spread of the virus.

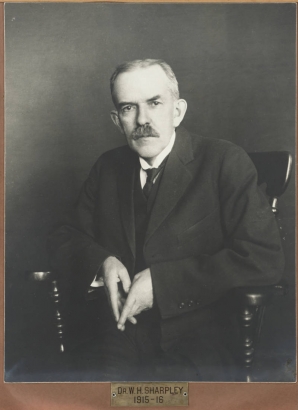

There were nineteen influenza-related deaths among Student Army Training Corps soldiers at the University of Colorado at Boulder in late September 1918, but Denver’s Manager of Health (and former Denver Mayor), Dr. William H. Sharpley, felt flu cases reported in his own city had been misdiagnosed. On October 3, 1918, the Rocky Mountain News declared Denver free of flu.

Two days later, the same newspaper reported 10 influenza-related deaths.

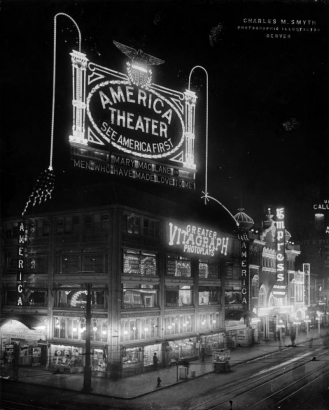

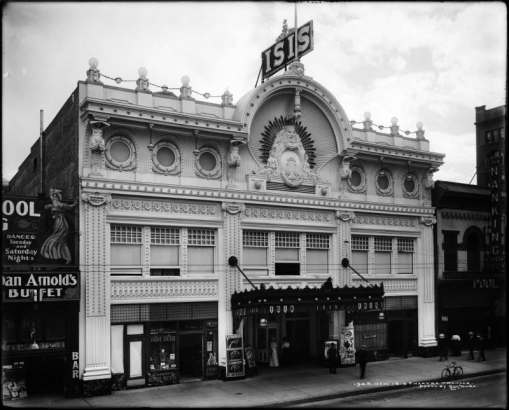

On October 5, Denver’s Board of Health ordered all schools, churches, theaters and places of amusement to close the following day. Indoor meetings were banned, and homeowners were told to stop burning leaves.

Shops, restaurants and other businesses were allowed to stay open and outdoor gatherings remained permitted.

On October 8, Dr. Sharpley proclaimed that “the plague is under control."

Meanwhile, he instructed Denver police to enforce spitting bans (while they discontinued brothel raids and arrests of vagrants for fear of bringing flu into the jail) and told the tramway to keep streetcar windows open. The city sanitation department now washed the downtown streets and sidewalks nightly.

Despite mandatory closures around Denver, there was still ample room for disease transmission. Outdoor meetings were still permitted (including a gathering of 40,000 people in Cheesman Park and a 10,000-person march to launch a Liberty Loan Drive). Streetcars remained crowded, and Denverites were still shopping and conducting business.

As death rates rose in October, Denver’s Board of Health went on to ban outdoor meetings, social gatherings in private homes and public funerals.

Nevertheless, death rates in Denver remained high until early November.

On November 11, Sharpley lifted the meeting ban. The day marked the end of World War I and thousands of citizens took to the streets in raucous celebration.

By mid-November, it seemed that life was returning to normal in Denver. Over the course of seven weeks, the city had seen 6,000 cases of influenza and 500 deaths. On November 21, Dr. Sharpley made a prediction that in another week, Denver’s death rate would return to normal.

He was wrong.

On November 22, 18 flu patients died and the closing ban was reinstated. Sharpley now required shoppers to wear gauze masks.

In Denver, the Spanish flu pandemic did not let up much over the course of December.

On January 3, 1919, the Denver Health Department released statistics for 1918. Some 12,718 influenza cases that resulted in 1,218 deaths were reported in Denver—a rate much higher than other cities of Denver's size.

The Influenza Pandemic of 1918 was a disaster for many reasons. The virus itself was a strong Type A H1N1 flu strain that caused bacterial pneumonia, for which there was no antibiotic treatment at the time.

Furthermore, there wasn't a central strategy to control the outbreak (the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention formed in 1946). Therefore, city and state health departments around the country grasped at straws to stave off the virus. Among the greatest challenges: delivering public health information quickly and enforcing orders effectively.

A more complete story of Denver's flu history can be found in the Western History and Genealogy Department within the following resources:

- Western History Subject Index (index to the local newspapers)

- Denver Municipal Facts (check out page 483 and 484 of the Denver Municipal Facts Index)

- Denver Public Library 1918 And 1919 Flu Obituary Index: Rocky Mountain News And Denver Post)

- Influenza Encyclopedia: Denver (online resource produced by the University of Michigan Center for the History of Medicine and Michigan Publishing)

- Rocky Mountain News Records (WH2129) - clipping and photograph files which focus on influenza outbreaks from roughly 1950-1990

Comments

One comparison that was left

One comparison that was left out of your numbers was that Colorado had 2.2 million people in 1968 versus 5.6 now. That means in comparison Colorado should have about 2500 deaths so far instead of the 11 to 1200.This is not meant to dismiss the toll in our state and country so far.

Is there an electronic list

Is there an electronic list available of all of the people in Denver by name who died from the flu in 1918?

Hi Bill,

Hi Bill,

Yes, those who died from influenza will have it indicated as "(flu)" next to their name in the 1915-1919 section of our Denver Obituary Project research tool.

Well done Katie. Sure is a

Well done Katie. Sure is a lot of similarities with our current virus.

My mother died in mid 1968

My mother died in mid 1968 from influenza flu symptoms, but the virus was unknown.

Add new comment