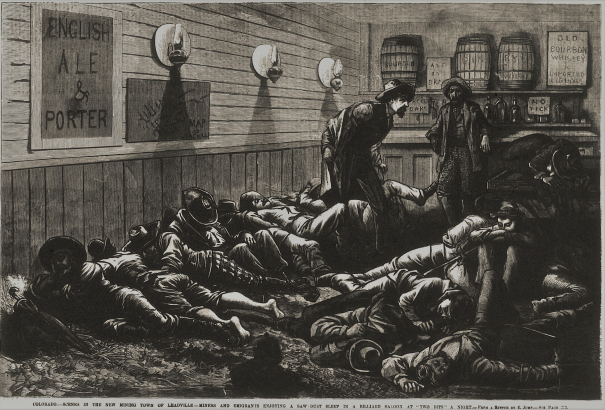

While the 1960s were, in many ways, a period of social revolutions, little reprieve came to those in need of housing. It didn't help that the massive flood of 1965 destroyed both traditional housing stock as well as encampments along the Platte Bottoms. At the same time, Larimer Street had developed a reputation as Denver’s skid row. Much of this stretch of downtown was populated by unemployed, underemployed, and retirement-age men. Alcoholism was rampant, and according to the Denver Post, many individual years saw thousands of arrests for drunkenness. Larimer was full of cheap hotels and flophouses where beds could be had for under a dollar. Many missions were also set up to help with addiction treatment and to serve as social alternatives to taverns. It was a world of unrelenting struggle that could have been ripped from the pages of Bukowski, or Zola for that matter.

Enter the 1960s solution to urban blight: the Denver Urban Renewal Authority (DURA). Funded by Housing and Urban Development along with a local bond, DURA oversaw the removal of much of the low-income housing in central downtown, as well as the largely Hispanic community of Auraria. While many homeowners were granted stipends to move and purchase comparable homes, this did little to aid the chronically unhoused. By 1969, some small strides had been made, including the establishment of the Wazee Center, meant to serve people seeking recovery from alcoholism, although many people continued to live along the river and even in abandoned boxcars.

The Wazee Center conducted studies of the men who utilized their services. A sampling of over 400 men appeared in the Denver Post on May 14, 1970, with some interesting results. The vast majority were white. Over half were divorced or separated from their spouses. Over 44% were military veterans. Two-thirds were over the age of 40. While the Wazee Center was able to serve 300 men per day, other businesses in Lower Downtown objected to having them as neighbors. The Center shut down in 1974, and DURA’s redevelopment of Skyline and Larimer Square continued to push the unhoused population toward 17th and Market Streets and further north along Larimer Street.

A new alcohol detox program began in 1974, but funding was cut the next year, reducing the number of beds from 134 to 24. Organizations such as the Men’s Assistance Center, the Salvation Army, and the Denver Rescue Mission attempted to fill in the gaps and shift more resources towards treatment needs, but efforts were seldom commensurate with the need. On November 4, 1977, the Denver Post ran an article highlighting a new focus by downtown law enforcement to “clear out winos.” Besides the usual round-up of those visibly intoxicated, police began focusing on “bootleggers” who would buy liquor during the day and sell it at inflated prices when liquor stores and taverns were closed. As one might imagine, and as pointed out by one detective who was interviewed, this did nothing to get at the root of the problem. The culture of the area had become so notorious that Tom Waits even mentions the corner of 17th and Wazee Streets in his 1975 song, “Nighthawks Postcard.”

By 1977, more attention was being paid to the impact of redlining in promoting detritus and eroding housing stock in poor communities of color. While redlining was officially ended by the Fair Housing Act of 1968, it was not until 1977 that the Community Reinvestment Act was passed in an effort to roll back decades of negative impacts caused by redlining. In Denver, the Lenders Mortgage Corporation was formed as a nonprofit with cooperation from seven lending institutions. As is the case with so many examples of systemic discrimination, undoing the damage has been difficult.

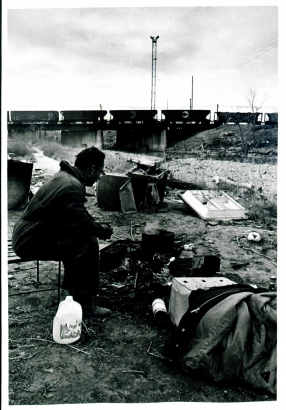

The 1980s brought a boom and bust in the oil markets that caused a new construction boom to end with a glut of abandoned buildings in downtown Denver. This ensured that, throughout the decade, Lower Downtown would continue to be known as Denver’s skid row. At the same time, the drop in tax revenue meant more reliance on the already struggling charities designed to serve people who were unhoused. A Rocky Mountain News article from December 24, 1989, followed Roy Chappell, a representative of the Salvation Army who would drive around trying to bring people out of the sub-zero temperatures and back to the shelter. He said that during the course of his four years at the job, he had brought in over 70 people who had been living under a single bridge over 8th Avenue and Speer Boulevard. Some had erected primitive plywood structures while others had less protection. Several of these people had to be transported to the hospital for treatment of frostbite.

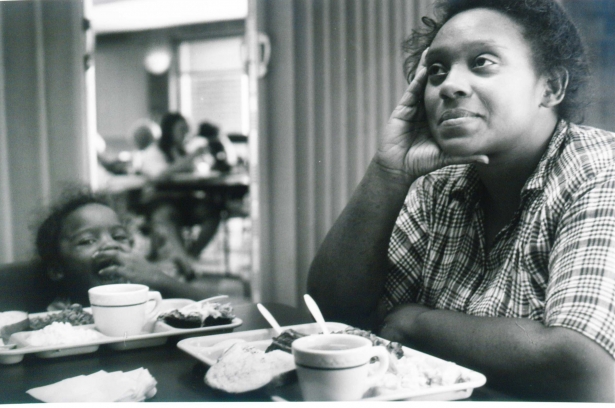

The 1990s brought no reprieve. A study released in 1991 showed the number of homeless families in the state had risen by 68% between 1988 and 1990. According to a Denver Post article from September 19,1991, the closure of Denver’s largest family shelter and major cuts to mental health programs both occurred within 1991. The same article quoted John Parvensky, director of the Colorado Coalition for the Homeless, who plainly stated,

“We're going in the wrong direction in dealing with this problem.”

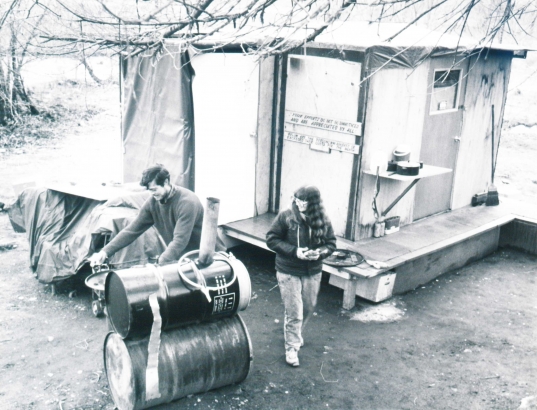

This theme echoes decade after decade in Denver. As downtown gentrification kicked off, more stories appeared in the press covering the construction of shacks and other makeshift housing along the banks of the Platte River. On April 26, 1992, the Rocky Mountain News even reported on an unhoused couple growing vegetables next to their plywood home along the river. It was a story that could have been written in 1870.

One of the more interesting 1990s communities was established along the Platte Bottoms under Park Avenue. It was named “Clintonville'' and had its own mayor, named Knuckles. The rules included “no violence, no drugs, no lies, and no stealing,” although alcohol was welcome. Residents were forced out in 1997 to make way for a new city park.

History, in this case, does not simply rhyme but continues to sing the same song. We don't yet know yet what the 21st century will see in terms of ending homelessness. That said, the early 21st-century boom in Denver's housing market is not a positive indicator.

If you want to learn more about how these issues impact people today and/or want to get involved, see the following links:

Colorado Coalition for the Homeless has an educational series.

Interfaith Alliance offers the opportunity for people to sign up for information on legislative action.

Denver's Office of Housing Stability serves as advocates.

Metro Denver Homeless Initiative offers the opportunity to join councils and committees to work on the issue.

Comments

Thank you for a very

Thank you for a very interesting article. I'm hoping there will soon be positive steps to address the issue.

Thank you for reading.

Thank you for reading. Hopefully, a glimpse into the past will help provide for steps that can be taken forward.

So appreciate this piece.

So appreciate this piece. Thank you.

Thank you so much for taking

Thank you so much for taking the time to read about this subject.

Thank you for this two-part

Thank you for this two-part article on homelessness in Denver history, which helps put current events in context. I do want to offer a correction to a photo caption in part one of the article. The photograph of a man reclining on a marble bench under a carved inscription reading "If thou desire rest desire not too much", is not the "Denver Post Building 1940s-1950s?" as stated in the caption. Rather, this bench and inscription are on the side of the Byron R. White Tenth Circuit U.S. Courthouse, formerly the U.S. Post Office Building, at 1823 Stout Street, Denver, completed in 1916. The bench and inscription can be seen there to this day. Here is a flickr link showing a recent photograph of it: https://www.flickr.com/photos/wallyg/6167434173.

Joseph, thank you so much for

Joseph, thank you so much for the correction. For some reason, the image in the Rocky Mountain News photo collection had "Denver Post Office Building" written on the back. I have updated the blog post and the image in the gallery. Good eye!

Ah, that solves the mystery.

Ah, that solves the mystery. It was in fact the "Denver Post Office Building" for many years, not the "Denver Post Building" (the newspaper's building). When it first opened in 1916, it was both the U.S. Post Office and Courthouse. The Post Office later expanded to take over virtually the entire building, and the U.S. courts moved a block over to a new building at 1929 Stout Street, erected in 1964. The Post Office building was reclaimed by the courts in 1994, after an extensive historic preservation effort essentially returned it to its 1916 appearance for use as the Byron R. White U.S. Courthouse for the Tenth Circuit Court of Appeals. https://www.gsa.gov/historic-buildings/byron-white-us-courthouse-denver-co

I'm beginning to think we

I'm beginning to think we might need to hire you, Joseph.

You mention Tom Waits--in the

You mention Tom Waits--in the '70s when he was in town performing at the Oxford Hotel (pre-renovation and kind of shabby) he used to hang out at the Terminal Bar, diagonal from the Oxford. It's now Jax Fish House.

I remember in the '80s when the Flour Mill Building was empty and a haven for homeless people. Now it's million-dollar condos. That's been the pattern downtown for some decades, accelerated in the last 10 years--the marginal parts of town where the homeless dwelt have been gentrified. Now there are no marginal parts of town and the homeless are shuffled around by the police from one "mainstream" area (e.g. Civic Center) to another. I know that the conditions of the flophouses of lower downtown in the '50s and '60s were bad, but at least the people weren't living on the street.

Thanks for the great insight

Thanks for the great insight into the patterns of housing that seem to run in circles. I am also jealous of anyone who got to see Waits perform in the 70s.

Add new comment