In 1869, New York tobacconist George Hull perpetrated one of the most infamous hoaxes in American history. What you may not know is that on the heels of his (mostly) successful ruse with the Cardiff Giant, Hull laid out plans for an even more elaborate deception; this one directly tied to Colorado. Though the Cardiff Giant had certainly been a triumph by some measure, it hadn’t succeeded in duping the scientific community as he had hoped. So, using the last of his depleted proceeds from the sale of the Cardiff Giant, Hull set up shop near Elkland, Pennsylvania.

Hull wanted to convince the scientific community that he had discovered the legendary “missing link,” and evidence of tool marks had been a dead giveaway that his first attempt had been carved. Hull was determined not to make the same mistake, so he diligently learned to make plaster molds, which he formed first on his son-in-law (until the cold and discomfort drove him to quit), and then on himself. He also developed, through trial and error, a custom mortar made of both organic and inorganic material, including ground bones and meat. When fired in a kiln, this mortar became suitably hardened, and took on a brownish tone which mimicked an appearance of antiquity.

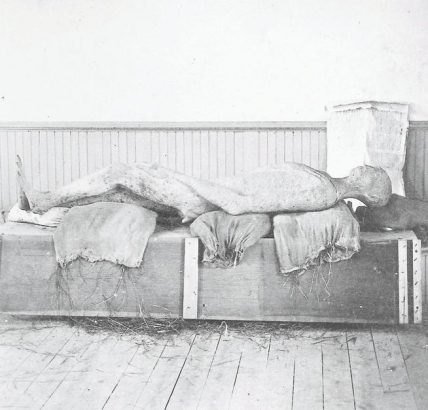

Hull purchased a human skeleton, which he placed within the framework of the assembled molds, and used the mortar to construct a facsimile of a petrified person (well, not really a “person,” per se). The effigy was a little under 7 1/2-feet tall, with extremely long (over 4-feet long) arms, almost comically oversized feet, and a curled 4-inch tail. The finished creation was beaten with needles embedded in lead to give the appearance of pores. In addition to creating this figure, Hull also crafted a number of “petrified” fruits, as well as a fish and a sea turtle.

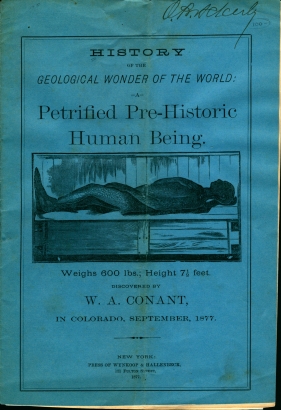

By the time he finished baking his creation, Hull was out of money. Remembering that P. T. Barnum had offered to purchase the Cardiff Giant, Hull reached out to see if Barnum would become an investor in his new scheme. Ultimately, Barnum fronted Hull two thousand dollars, in exchange for a whopping 75% stake in his newest undertaking. Barnum drew up a contract, dubbing their partnership “The Giant Company” and then introduced Hull to an associate, William Conant. Barnum sent the two to Colorado to do some location scouting. At this point, Hull began using an alias (most often "George Davis"), to avoid anyone making an association between the soon-to-be-made giant discovery, and the other recent giant discovery.

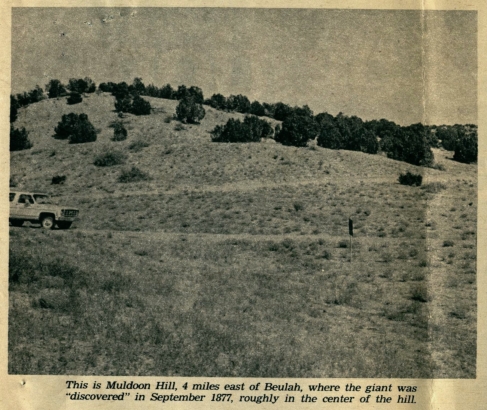

Ultimately, they decided that a small hill about five miles outside of Beulah, Colorado, would serve their purposes. Once they had settled on this location, they began working towards the next phase: the reveal. One of Conant’s sons, Fred, happened to be the editor of a Colorado Springs newspaper, The Colorado Mountaineer. Hull and Conant, Sr. employed the services of a local rock hound named Lewis Allen and arranged to have him “find” a number of the smaller “fossils” that Hull had created. Conant’s son then dutifully ran stories about these discoveries in his paper, seeding public perception with the notion that the region around Pueblo and Beulah was teeming with untapped archeological resources.

When the time came, the giant was shipped to Colorado Springs by rail (in a boxed marked “machinery”), and Conant, Hull and Allen surreptitiously buried it in the predetermined location. It was left for several months, both so people wouldn’t associate the large crate which had recently arrived with the sudden appearance of a petrified man, and also to let the site settle, so there wasn’t evidence of recent tampering. Hull took a back seat during the discovery and display of his creation, adopting the guise of a humble assistant to Mr. Conant, for fear that someone might recognize him for who he truly was. William Conant, and his (other) son, Will, “discovered” the figure on September 16, 1877.

With the help of Fred Conant’s paper, the news of this amazing discovery spread quickly. By a staggering coincidence, famous showman P. T. Barnum just happened to be in Denver giving a talk to a temperance organization when the discovery was made. He decided to swing down to Pueblo to check it out, since he happened to be in the neighborhood anyway, and stirred up even more public interest when he publicly offered to buy the curiosity for $20,000. Many were skeptical, while others were swayed…and, most importantly, many people were curious enough to shell out fifty cents to take a gander at the mysterious Petrified Man. The Colorado Chieftain dubbed the figure the Solid Muldoon, inspired by an Edward Harrigan's Irish ditty, which contained the line, “There goes Muldoon, he’s a solid man.”

And the solid man did go…for a while. Muldoon was paraded around Colorado and Nebraska before being ushered all the way back to New York, where oddities always drew a curious crowd. However, its lifespan was ultimately fairly short. Hull had overextended himself quite a bit during the manufacture of his humbug, his debts far exceeding the paltry two thousand that Barnum had fronted him. Hull had promised one man, E. J. Cox, half of his share in the proceeds once the Colorado Giant had been revealed. What Hull failed to mention was that by that point he only owned around 12% of his creation, having doled out parts of his portion to numerous people (either for their assistance, or their silence). When Cox discovered that he was looking at far too much of a pittance to make a dent in the amount he had shelled out (at least in the short term), Cox got rather upset, and went to the press, revealing everything he knew about the hoax, including the true identity of George Davis.

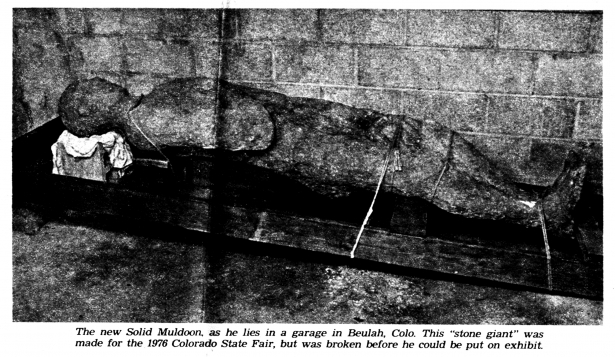

Unlike the Cardiff Giant, which still drew curious onlookers, interest dropped off almost immediately once the fraud was revealed. The Muldoon quickly faded from public attention, and nobody - not even the Beulah Historical Society - is sure what ultimately happened to the original. However, in 1976, as part of Colorado's centennial celebration, an artist recreated the figure, and the replica was buried near where the original “discovery” was made, on what is now known as Muldoon Hill, just outside Beulah. The grave marker shown at the top of the page marks its resting place.

For more intriguing stories about Colorado and the West, visit Western History and Genealogy, and like our Facebook page!

Sources:

From Mace's Hole, the Way it Was...

Howdy, Sucker! What P.T. Barnum did in Colorado

History of the Geological Wonder of the World

Comments

Thanks for such a great post,

Thanks for such a great post, Chris! For anyone wanting to visit this Solid Muldoon "Point of Interest", the site also offers a beautiful view of mountains surrounding Beulah Valley, where another nefarious figure in Beulah history used to hide his stolen cattle (Beulah was originally called Mace's Hole). Now that I work in preservation of collections, my guess is that the original Solid Muldoon just didn't hold up over time - I don't think of baked ground meat and dried fruit as preservation-quality materials!

Thanks for the comment, Becky

Thanks for the comment, Becky! I suspect that there's a reason that meat-based ceramics never caught on.

Your stereoviews were

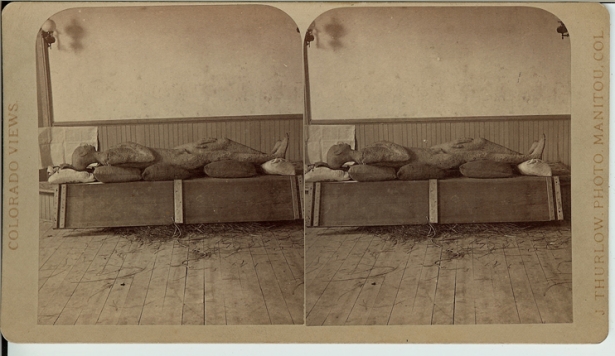

Your stereoviews were produced by James Thurlow, Manitou's first photographer (1874-78). He also produced a variation of that side view showing the prehensile tail, and a close-up of just the head, as well as a 4x7-inch non-stereo image of the better view shown above. Other period photographers also published copies of the stereoviews; I have one by Shipler and Williamson, who were active in Denver in 1877.

You had me at “Solid Muldoon”

You had me at “Solid Muldoon”.

Does anyone know where the…

Does anyone know where the original Solid Muldoon ended up? not the replica bored near Beulah? davebear@centuytel.net

Add new comment