Why does Denver hold its mayoral elections in the spring instead of pairing it with the general elections that are normally held in November? That’s a question plenty of Denver voters will be asking as they choose the Mile High City’s 46th Mayor on April 4.

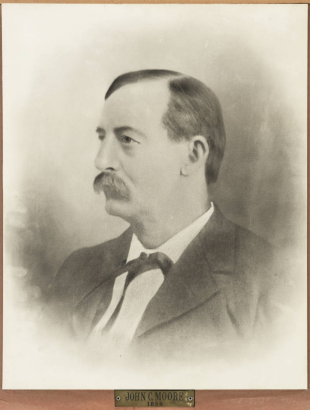

Denver’s history of April mayoral elections dates back to a cycle of elections that actually began in December of 1859 when John C. Moore was elected as Denver’s first mayor. Moore came into office under the authority of an entity which itself had no actual authority, the Jefferson Territory (J.T.). This attempt at carving out what is now Colorado from the Kansas Territory was intended to build a government that was closer to the Pike’s Peak gold regions. The effort turned into a complete failure and the J.T. was recognized by no one outside of its made-up borders.

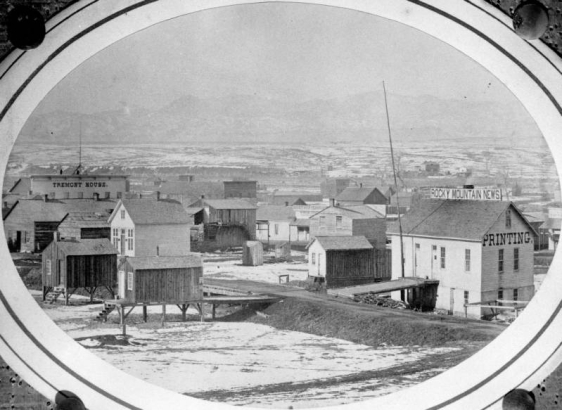

December 1859 is also, not coincidentally, the same time that the settlers of Cherry Creek consolidated the towns of Denver, Auraria and Highlands into a single municipal government. They spelled out their plans to form a municipal government in a document that was enacted by “...the Provisional Government of the Territory of Jefferson.” (Smiley, 632). That J.T. was not then recognized, nor would ever be recognized, by the government of the United States did not matter to anyone involved.

That document set an election for December 1859, and that “the regular annual election should be held on the first Monday of October in each year thereafter.”

Moore’s first term was set to last until October 1860, but the political representatives of the J.T. were simply not cut out for that kind of work. By mid-year, they’d lost their mojo and were “weak and inefficient” according to Jerome Smiley’s description in History of Denver. Moore was so disengaged that in the fall of 1860, Denver residents took matters into their own hands forming a new city government called “The People’s Government of the City of Denver”.

They consolidated their plan in a document titled, Constitution: people’s government of the city of Denver (C342.788 C713c 1860). Section 17 of that document reads,

All elective officers of this government shall be filled by election of the people, on the first Monday in October A.D. 1860, and semi-annually on the first Monday of April and first Monday of October thereafter, and they shall hold their respective offices until their successors are elected and qualified.

The People’s Constitution also called for immediate elections of city officers such as judges and city council representatives who would serve a term lasting until the spring of 1861. The office of mayor is conspicuously absent from the list of elected officers. It seems as though Moore, at least on paper, remained mayor.

Moore proved himself to be completely unfit for office sometime in 1861 when he fled Denver to join the insurgents of the so-called Confederate States of America. He fought against the U.S. Army with the Missouri State Guards and fled to Mexico to fight with the troops of Maximillian after the war. The disgraced former mayor eventually returned to Colorado, living in Pueblo for a time before retiring to Missouri.

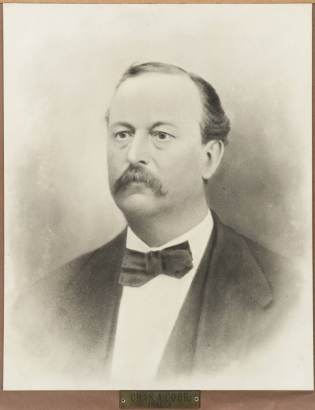

In April 1861, Denver elected a stagecoach executive named Charles Cook as mayor for what would prove to be an interesting and transformative time for the city. That’s because in February 1861 the Colorado Territory (C.T.) was created by President James Buchanan.

The Legislative Assembly of the Colorado Territory met for the first time in November 1861 and made Denver a legally recognized entity. In doing so, they adopted, almost word for word, the plans laid out in the People’s Constitution and approved an election for Denver that was held on November 18, 1861.

Cook was reelected in April 1862, and Denver’s run of springtime mayoral elections has been mostly uninterrupted since then. The cycle went off-kilter in October 1877 when Baxter Stiles replaced the highly unpopular Dr. R.G. Buckingham in the same election in which women’s suffrage was on the ballot.

Springtime elections returned in April 1883 after the terms of Stiles (October 1877-October 1878); Richard Sopris (October 1878-November 1881); and Robert Morris (November 1881-April 1883). After that, Denver’s mayors bloomed exclusively in the springtime with the exception of four-term officeholder Bill McNichols, who stepped in for outgoing mayor Tom Currigan, who left office in December 1968 to work for Continental Airlines because the pay was better. McNichols, who was frugal enough to live on a city salary, remained in office until 1983.

The story of Denver’s springtime elections is convoluted and much of the documentation of the early elections was lost in floods and fires that occurred in 1863, 1864, 1875, and 1885, to name but a few.

It’s also worth noting that springtime elections are still held in a number of U.S. cities including Colorado Springs; Dover, Delaware; Jacksonville, Florida; and Springfield, Illinois.

So why have springtime elections in the first place? The historical record is not particularly clear on this point. Given that many residents of the settlements along Cherry Creek would return to Kansas Territory for the winter to resupply, it’s possible that fall elections simply weren’t viable. Regardless, the entirely unsatisfying answer to this question seems to be, "Because that's the way we've always done it."

Sources Cited:

Denver Mayor’s Speeches, Inaugural and State of the City, 1859-2019

Colorado Chronology, Roger Dudley, 2020.

Colorado Historic Newspaper Collection

United States mayoral elections, 2023, Ballotopedia

![African Americans Omar Blair, representing the Denver Urban Renewal Authority and the Rev. Cecil W. Howard, of the Shorter Community AME Church, along with Denver Mayor William H. McNichols hold shovels at the ground breaking for the Denver Urban Renewal Authority Whittier project in the Whittier neighborhood of Denver, Colorado. A sign reads, "(?) R-4 15,824 Square feet, Building Sit[e] [o]ffered by Denver [Urba]n Renewal Author[ity]."](/sites/history/files/styles/blog_image/public/cdm_62939_0.jpg?itok=scbtliDg)

Comments

Your "homebound" service is

Your "homebound" service is remarkable to me, because I am relatively new to the city, and getting around in it is very difficult for me. Moreover, I do not have an automobile; Thus I appreciate very much, all you do!

Add new comment