Arranging affordable, quality child care has been a challenge for working families in America for more than a century. While the COVID-19 pandemic brought the dilemma of juggling child care and work to the forefront of media attention, this problem is hardly a new concern for parents. In fact, just a few minutes of research into our newspaper index and clipping files produces ample stories that reference the struggle as far back as the earliest decades of the 20th century. In the 1910s, to address this need, several Denver organizations founded child care centers. Among these new nurseries (as they were then called) was the city’s first racially integrated day care: the George Washington Carver Day Nursery in the Five Points Neighborhood.

In 1916, reports circulated of the deaths of two white children who were left unattended at home while their parents worked. In response, the women of the Negro Woman’s Club Association of Denver (NWCA) saw the necessity of providing a reliable, safe, and affordable option for children during the day. Up to that point, the club’s headquarters at 2357 Clarkson had served as a meeting place for the various artistic and cultural clubs that comprised the NWCA. The building also served as a rooming house for working women, with Mrs. Mildred Westbrook (wife of Dr. Joseph Westbrook) as the first matron in charge. Many of the home’s residents are listed in city directories as working as maids and cooks for Denver institutions like Mercy Hospital, the high-end St. James Hotel, and O.P. Baur’s Confectionary, as well as for private families. Several of these women boarders had difficulty finding affordable child care for their children, which served as further impetus for the NWCA to act.

Opening in March 1916 as the “Negro Women’s Club Association Day Nursery,” the NWCA’s childcare program offered daytime care on weekdays for children ranging from infants to school age. For a daily rate of $0.10 per child per week ($0.25 for 3), the school provided supervision, enrichment activities, a daily lunch and snacks, a playground, and regular doctor’s visits onsite.

Over the years, their students put on holiday plays and fashion shows, and benefited from an intentional play-based curriculum that focused on building independence and life skills in addition to art, singing, and the ABCs. In their first year, the Club Association building housed 16 women and cared for 3,128 children.

In the first half of the 20th century, at a time when racial segregation predominated and was enforced by practices like real estate redlining, the NWCA’s insistence on serving all children regardless of race or creed was revolutionary. The neighborhood of Five Points was highly diverse, with significant Hispanic American and Asian American communities, in addition to the African American community for which the neighborhood is best known. Thus the new nursery also provided their charges with an early education in the benefits of diversity.

The school and home were able to offer their services at a low cost because NWCA-affiliated clubs provided financial support through their monthly dues, personal donations, and fundraisers. The school became a recipient of the Community Chest, then the United Way Fund, and in 1948 changed its name to the one by which it still operates, the “George Washington Carver Day Nursery.”

Eventually educating and caring for children from 2 1/2 to 12 years old, the school became an integral part of the Five Points and later Whittier and City Park West neighborhoods. Many influential members of the area’s African American community served on the board and provided additional financial support to the school.

The first nursery director, the aforementioned Mildred Westbrook, set the nursery’s tone of loving care; one story recounts her taking children home with her overnight during a blizzard, when their parents were unable to reach the school in time for closing.

Continuing the school’s development, much of its educational philosophy can be attributed to the second director, Erma L. Ford. A working mother with three children of her own, Ms. Ford obtained a bachelor of arts degree in Elementary Education. She initially worked as a Denver Public Schools kindergarten teacher, then served as Carver’s executive director from 1947 through her retirement in 1980.

In the early 1960s, having outgrown its space, the Carver Board of Directors launched a fundraising campaign that eventually brought in more than $50,000. On March 20, 1966, after fifty years serving Denver families on Clarkson, the school moved to a new location at 2270 Humboldt Street, where it remains in operation today. The ribbon cutting event is well-documented in the Burnis McCloud and Clarence and Fairfax Holmes Papers.

Over the past century, press and community messages about the school were primarily congratulatory. Governor Richard Lamm declared October 20, 1978, "George Washington Carver Day Nursery Day," in honor of the “more than thirty thousand” students Carver had lovingly served to that point.

In contrast, media coverage at different periods also displayed bias against people of color, the working class, and single parents. These articles, while generally praising in tone, were misguided in their assumptions, referring to the school as serving unfortunate children “from broken homes,” and as working to “ease the welfare department load.”

A further challenge the school faced was a February 1980 fire set by arsonists who were never caught. The fire caused significant damage to the building’s interior, forcing parents of half of the then 114 enrolled children to find alternative care. Much as the Carver school served the needs of Denver parents, the community responded in kind. Nearby New Hope Baptist Church offered classroom space while the school building was repaired, and a fundraiser and large anonymous donations brought in $40,000 to help with the school’s recovery.

The George Washington Carver Day Nursery has been in operation for 105 years and counting. The school was founded at a time when working families were statistically less common than they are today, and support for working parents was scarce. Carver operated through the Depression and the post-WWII years, when society heaped judgment on working women and single parents. Through these eras, and facing racial bias and even arson, the school provided a crucial service for families. Carver allowed parents to maintain financial independence and pursue careers, while the school protected, educated, and helped raise tens of thousands of Denver’s children.

For more information on the school or its founders with the Negro Woman’s Club Association, we welcome you to visit the library and see the George Washington Carver Day Nursery Records collection.

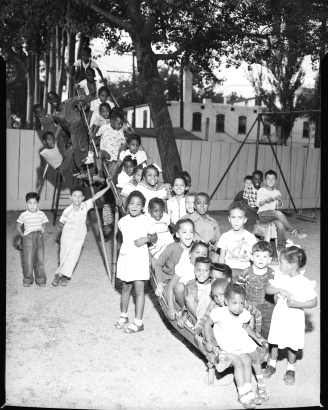

We are currently digitizing images from and related to the school, and would welcome identifications of some of the people featured. These images will be found in our digital collection, in a George Washington Carver photo gallery, and in the physical collection.

Comments

I read a book about him when…

I read a book about him when i was 7 and remember how he was taught to read by a white woman developed 1600 ways to use peanuts and 1100 ways to use soybeans rotating crops in order to stop using fertilizer he was an amazing man i rest my case

Hello everyone, I am Sam…

Hello everyone, I am Sam Harrison from LA, Connecticut. I want to recommend Mr Brian Stone and his team who has had to deal with these internet swindlers, I lost my entire savings after investing in a cryptocurrency platform, I was told I would gain huge profits from my investment not knowing they were setting me up for a huge scam. If you have had a similar experience, I strongly recommend you contact brienstone02@gmail.com or WhatsApp him +1 (336)257-8835. as they were able to recover all my money in 48 hours. They are the best when it comes to recovering stolen money from these online swindlers. Reach them direct: brienstone02@gmail.com or via their Telegram: t.me/brainStones

Add new comment