-By Stevie Gunter (Guest Blogger)

My name is Stevie Gunter (they/them) and I’m Black, gendervoid, and an Archivist Librarian at Denver Public Library’s Blair-Caldwell African American Research Library. These identities help to contextualize my work, as I consider the uses of fluidity and refusal of naming in the archives. My work is informed by transnational feminism, which critically engages with settler colonialism, imperialism, neoliberalism, and heteronormative gender constructs. I’ve been digitizing and creating metadata for 14 collections at Blair-Caldwell since December 2020. This project is funded by a grant from the Institute of Museum and Library Services, Museum Grants for African American History and Culture.

I earned my Master’s in Library and Information Science from the University of Denver in 2020. I had been working on a documentary project, Seeking Grace: Black Women Finding Self, which gave me the opportunity to become familiar with the cultural memory and movements of Black people living west of the Mississippi River. Despite not being raised in Denver, my perspective of this region has been shaped by Black feminist research practices. This project appealed to my experience, knowledge, and research interests. I’ve also fostered a desire to steward Black narratives which exist in the foggy margins of the mainstream image. Having previously worked with analog formats in D.U.’s Special Collections and Archives, I was also drawn to the wide range of “hats” I would wear in executing this work. I get to digitize 14 of the most heavily used collections, work with a talented staff to develop a digital exhibition, and collaborate with local educators to create teaching kits, informing how Black history is taught.

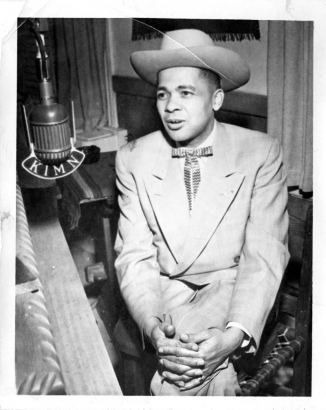

This position gives me the opportunity to dig deeply into the details of each collection, which also provides opportunities to creatively think about their use in other contexts. I approach the work not only as a skilled archivist, but as a storyteller. When photographs of Leroy Smith and his family are found in the Lincoln Hills collection, or when the speeches of Arie Parks Taylor mentions locations that Rachel B. Noel and others had activated around in moments of tension and movement, I ask questions of the archives. How did these people relate to their sense of place and placemaking, their impact on their communities and how they changed, how did they witness each other, and where else will I find them?

The collections are presented as separate entities but this work brings into focus the fact that, before their experiences were collected, they were our neighbors. With archival literacy and education being key components to this position, I’m constantly considering how to put these collections in conversation with one another and today’s public. These histories are very much alive and it’s fun to showcase that knowing that’s what people seek when visiting Blair-Caldwell.

Documenting cultural heritage artifacts has become increasingly relevant during the limited access we’ve experienced at public libraries due to the COVID-19 pandemic. It’s also important to have stories of resistance,celebration, and joy to be grounded in, especially in the wake of the collective trauma stemming from viral, recorded testimony of police violence against queer and BIPOC people in the United States in recent years. The items of each collection, especially when taken as a constellation altogether, gives the community the opportunity to see how Denver’s history is Black history. These archives show how this city and the surrounding region has been shaped by Black people finding a way under an intersection of numerous oppressions, including erasure from our region’s memory.

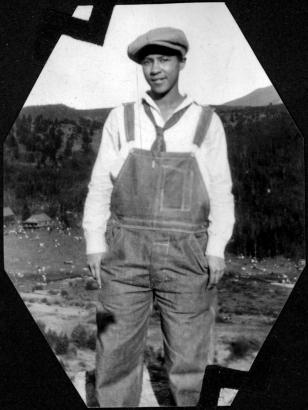

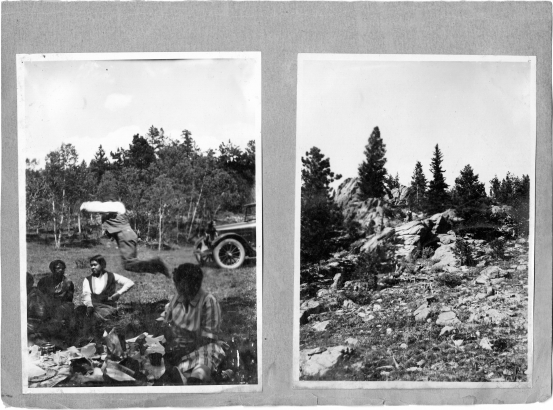

Several months into this position, I have two categories of favorite materials. The first includes proof of Black people thriving during Colorado’s Ku Klux Klan era. The Lincoln Hills collection documents Black land ownership and enjoyment of outdoors that, as a Denver newcomer, was a joy to discover for myself. Colorado is popularly characterized as a place where people who love to be outdoors can find community, but rarely do we see Black people as a part of that image. This collection is incredible because most of the individuals who endorsed the Lincoln Hills Company at its height in the 1920s-40s were Black business men and women, and many of the latter actually owned land.

The second category is that of activists and politicians who were persistent in working for liberation. Arie Parks Taylor was a powerhouse of a legislator who was vocal about her values and care for not only her constituents, but marginalized Denverites in general. She was the first Black woman elected to the Colorado House of Representatives in 1972. By 1974, she sponsored nearly 30 house bills as a State Representative which addressed justice in education, consumer affairs, taxes, healthcare, discrimination, campaign reform, and other issues. While not all were passed, and she gained a few rivals in other districts because of her progressive values, she continued to push for the kind of change that would help lay the foundation for Black feminist elected leadership in the state.

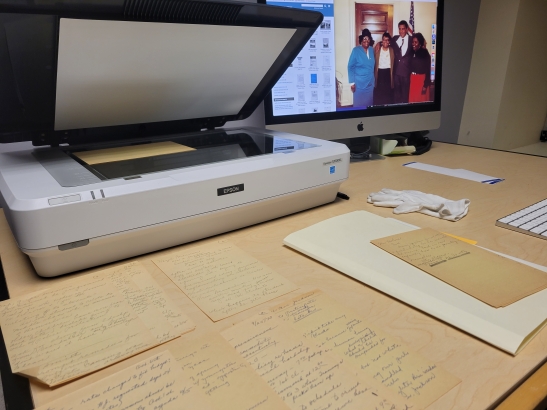

Special collections hold materials that are rare, often in delicate condition, which require intentional storage and security. These materials are usually accessed in person with staff supervision. Most of the formats and types of materials in our collections are easily digitizable with the right equipment, which can support access in many ways. On one hand, we want to make these items available to researchers who may not be able to visit in-person for a myriad of reasons. On the other hand, we want to ensure that the equipment we use can be accessible to our community in the future for continuing to record Denver’s unique history.

The IMLS grant that has created this opportunity for me is a part of a larger legacy of supporting the capacity and growth of professionals at African American knowledge institutions. There has been a steady positive trend in financial support for content digitization over the past decade. I get to learn from the expertise of my colleagues who have digitized some of Denver’s Black history in the past in order to troubleshoot issues that may come up as well as potential barriers to access. The scale of this project is immense, which has shed light on the ways in which we can organize collections from both an analog and digital standpoint moving forward. This creates the opportunity for researchers to efficiently find related materials across a wide array of boxes, in a digital interface.

As a Black archivist in a department that is primarily white, I believe my attunement to the lived experiences of Black people and Black memory work is legitimized in the roles I fulfill. A Black, queer archival practice to me means that stewarding the archives is care practice. We are meant to celebrate - not only document, digitize, and describe - Black life. Working at Blair-Caldwell with amazing Black staff drives my desire to skillfully embody the history of which I’m a part (and to recognize that as a legitimate archive as well). I’m thinking of my colleague, Terry Nelson, who has been a powerful resource in helping me identify individuals in photographs and detail the emotional and political impact of many of the subjects for which I’m creating metadata. Themes such as displacement, gentrification, and the legibility and uniqueness of Blair-Caldwell’s archives are daily conversations that characterize how I advocate for our role in the community. Centering these reflections while helping to carry out the work of digitization, access, and education makes this Black archival practice restorative.

My hopes for the future of my work is to make my job irrelevant. As archivists, we have to contend with the fact that a function of the archives is gatekeeping. I imagine our community recognizing, through future outreach and funding, that Blair-Caldwell is their space to record our histories in widely affirming ways. A part of that vision includes using technologies that are accessible and fun, and I think that begins in our digitization lab. If our visitors are equipped to build their personal archives while also contributing to our collections, that can promote equity through skill sharing and expand opportunities for traditionally excluded narratives to be recorded in ways that are based in participation and consent. In the meantime, I’m looking forward to building exhibits and teaching kits with different community members. These collaborations are just the beginning of the work needed to challenge the privileges and powers we have as educators and curators of our histories, and I’m excited to be working toward this goal in community with you all.

Comments

Absolutely brilliant! I'd

Absolutely brilliant! I'd love to connect and hear more about what you're working on.

Thank you, Philip! Stay tuned

Thank you, Philip! Stay tuned for further updates on this project, and feel free to get connected with the Blair-Caldwell branch for more details.

Add new comment