On the afternoon of October 31, 1880, two Chinese men were attempting to enjoy a game of pool at a saloon on 16th and Wazee known as John’s Place when a group of men began accosting them. Despite several attempts to cool the situation down, and spirit the Chinese men to safety, the incident quickly spiraled into a full-blown race riot.

By the time the authorities got the situation under control, nearly every Chinese-owned business in the city had been burned down, dozens of Chinese were injured, and one man, Sing Lee, lay dead.

The Denver anti-Chinese riot of 1880 is one of the most shameful episodes in Denver’s history. Its toxic mixture of racism, alcohol, and misinformation led to the near complete demolishment of Denver’s once-thriving Chinatown.

Financially, the riot did approximately $53,000 worth of damage, about $1.3 million in today’s dollars. Despite attempts by the Chinese government to recover damages on behalf of its citizens (a courtesy the Chinese had extended to American missionaries who suffered financial losses during riots in China), none of the Chinese business owners received any sort of compensation for their losses. For the most part, Denver’s Chinese population fled the city and faded into history.

But who were the men (and they were mostly men) who traveled from China to Denver, only to see their dreams go up in flames? Though the story of the Denver anti-Chinese riot has been told regularly for the past 130 years, very few historians have bothered to learn much about who the Chinese of 1880 really were. Fortunately for contemporary researchers, Liping Zhu, author of The Road to Exclusion: The Denver Riot, 1880 Election and the Rise of the West, has delved into the topic in some detail.

Using U.S. Census records, Denver directories, historic newspapers, and plenty of long hours of research, Zhu paints a very compelling picture of the lives of Denver’s Chinese population on the eve of its destruction in 1880. Along the way, these people turn from faceless victims into living people who had lives and dreams, just like anybody else.

Chinese Workers on the the American Frontier

No one knows exactly when the first Chinese came to Colorado. Unconfirmed reports place the first arrival at around 1866. More credible sources, however, suggest that at least four Chinese miners came to Colorado from Wyoming Territory in 1869, and several were known to have been in Georgetown as early as 1870.

In 1870, Colorado Territorial Governor Edward McCook actually invited Chinese workers to come to Colorado to help alleviate labor shortages and work mining claims. Though McCook promised Chinese immigrants to Colorado the full protection of the law, he also referred to them as both an “inferior race” and “pagans.” Either way, McCook saw foreign-born labor as the answer to Colorado's labor shortage.

The Chinese who did make their way to Colorado were, in many ways, very different from the Territory’s European and native-born miners and settlers. For starters, most of them weren’t planning to stay in Colorado, or North America for that matter, for an extended period of time. Though their average stay was about six years, most Chinese laborers were working and saving with the intention of returning to China to live on their earnings. Zhu points out that the average Chinese worker could save about $30 a month and return home after six years with about $2,000 to, effectively, retire. That, of course, assumed that they both survived their journey to the U.S. and made it home with their savings intact — which was in no way guaranteed.

Unlike their native-born counterparts, who came to Colorado from the East, the vast majority of Chinese workers in Colorado came from points west, where they usually had already been working as miners or railroad workers. This meant that most of the Chinese working in Colorado had experienced life on the frontier to some significant extrent.

Almost everywhere they went in the Trans-Mississippi West, the Chinese distinguished themselves as extremely hard and motivated workers. Chinese miners were adept at squeezing out gold from claims that other miners had abandoned as spent. Zhu cites reports of Chinese miners using fires to thaw frozen ground so that placer mining could be turned into a year-round activity. This extreme work ethic was no doubt motivated by a desire to return home to life of relative ease compared with the hardships of the frontier.

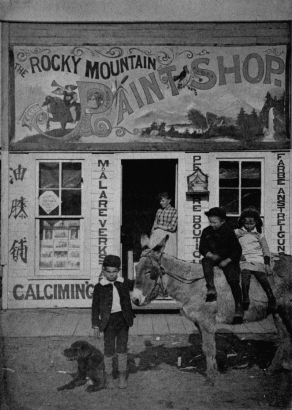

But it wasn't just in the gold fields where Chinese workers thrived. In both mining camps and in towns, including Denver, Chinese men found a lucrative niche running laundry services. At the time, laundry was considered “women’s work,” but women were in extremely short supply on the frontier. Chinese men stepped into this void and absolutely dominated the laundry trade in places like Denver. With its low overhead, it was a business that could be started almost anywhere by anyone willing to work hard.

The Chinese Population in Denver

Denver in 1880 had a relatively robust Chinese population of about 238, of which 225 were men. Almost all of these men worked in, or owned, laundry services. Of the relatively few Chinese women in Denver at the time, most worked as prostitutes, though a few were employed in other occupations.

For the most part, Denver’s Chinese population was accepted into daily life. Because Chinese laundries weren’t competing with Caucasian businesses and provided an essential service, they operated without much interference from their white neighbors.

In Road to Exclusion, Zhu notes that Denverites enjoyed Chinese New Year, which was celebrated with fireworks and a live-and-let-live attitude. Locals also took a keen interest in traditional Chinese funeral processions, which regularly snaked through Denver streets. A notable exception to Denver’s atmosphere of acceptance was the Rocky Mountain News (RMN), which routinely printed virulently anti-Chinese editorials leading up to, and after, the riot.

But the RMN was hardly alone in its thinking. Racism directed at Chinese immigrants was common during this period, as the riot of 1880 made all too clear. But it didn't take too much to ignite the flames of racial hatred, as the events of that fateful fall day made painfully clear. What started out as a minor pool hall beef exploded into an orgy of mayhem and violence that destroyed years of hard work, health, and happiness in mere moments.

Though much is made of efforts by Denver residents, police, and firefighters to protect their Chinese neighbors, these actions were dwarfed by the actions of a malicious mob that numbered in the thousands and was dead set on racially motivated mayhem.

Aftermath

When the riot finally died down, a Chinese man who is commonly referred to as Sing Lee, but was actually named Look Young, had been murdered, dozens were severely injured, and Denver’s Chinatown had been all but erased.

Almost immediately, about 100 of Denver’s Chinese residents left town. This included a group of women whose tickets were paid for by Denver madame Mattie Silks. Many more residents were left with nothing but burned down businesses and dashed dreams. This is to say nothing of the trauma that they would carry from the terrifying experiences of October 31, 1880.

Estimates of the total damage range from $20,000 on the low end to $53,000 on the higher side. The financial losses incurred by Chinese workers during the riot were almost certainly much higher, but since so many victims had fled Denver before the losses were tallied, the true extent of the riot will never be known.

Regardless, this was the number submitted by the Chinese government in an attempt to recoup its citizens’ losses. Though China had paid considerably more to the U.S. government when Americans suffered losses during riots in China, Denver’s Chinese business owners never received any compensation for their losses.

Justice, in the form of criminal indictments and convictions, was also in short supply. The rioters who unleashed murder and mayhem were barely held accountable and Lee’s murderers got away with short one-year prison sentences, although it’s unclear if they actually served those sentences.

The fate of Denver’s Chinese population after the riot is also largely unknown. It’s likely that many of these people simply started over in new places, as returning to China empty-handed probably wasn’t a viable option. Either way, Denver’s Chinatown never really returned and anti-Chinese sentiment won both the battle and the war.

Barely a year later, in 1882, the U.S. Government enacted the Chinese Exclusion Act, the only law that specifically barred members of a certain ethnic group from immigrating to the United States.

![A Chinese man poses on a wooden sidewalk near a business district possibly in Colorado. A nearby sign on a building reads: "[?]ng Lee [La]undry".](/sites/history/files/styles/blog_image/public/cdm_21625_0.jpg?itok=rCvC5oNw)

Comments

Very interesting article —

Very interesting article — and very sad to see such racism continuing in some places.

Thanks for posting, Mike.

Thanks for posting, Mike. There is a real element of "sameness" to the historical record that is very sad indeed.

Agree with your statement. I

Agree with your statement. I think to some extent , just being different to what one is accustomed to, being skin color, physical appearance, language, practice of religion, and envy of another’s success will bring about a challenge to one’s self value. Hate has been around since Cain killed his Brother. Not an easy problem to solve but must keep trying for the sake of everyone’s future !

Thank you, Wanda!

Thank you, Wanda!

A Chinese man known as John

A Chinese man known as John Touk was employed by Louis Dupuy as a gardener at Hotel de Paris. Touk occupied Room 1 of the Annex building and in addition to gardening, likely ran the hotel's laundry. He is listed in the 1885 Colorado census, and may have fled Denver to Georgetown, which had a small Chinese population (some of whom constructed parts of Hotel de Paris).

Hi Kevin - Thanks for posting

Hi Kevin - Thanks for posting! Zhu found that many Chinese-run laundries didn't appear in the directories at the time, but was able to suss them out from other sources. But it's a near certainty that a Chinese man was running the laundry almost everywhere it was offered as a service.

Excellent blog Brian! It's

Excellent blog Brian! It's well past time to shed light on the darker parts of Denver's history.

Thanks, Shelby! Zhu's work

Thanks, Shelby! Zhu's work really fills out this story in a way that hadn't really been done before. It's definitely worth a read.

I appreciate your coverage of

I appreciate your coverage of this event. I had just recently heard about it but didn't know the details or the events that happened after.

Thanks, Tiff! The riot itself

Thanks, Tiff! The riot itself burned out pretty quickly, but the aftermath had to have been around for a very long time. Thanks for reading and commenting!

Add new comment