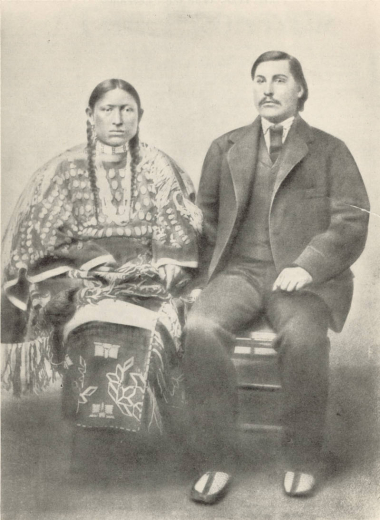

Cheyenne-American interpreter and historian who often found himself caught between his mother's Cheyenne world and his father's white American world.

George Bent was born July 7, 1843 at Bent’s Fort. He was the son of two of early Colorado’s most important people.

His father, William Bent, was a famous trader of fur and supplies. William and his brother built Bent’s Fort, one of the busiest trading posts in the West.

George’s mother, Owl Woman, was the daughter of a respected medicine man from the Cheyenne tribe. William Bent became an honorary chief of the Cheyenne after their marriage.

For many years Owl Woman and William Bent helped create peace and understanding between the Cheyenne and white settlers.

George Bent was raised according to Cheyenne customs, and went by his Cheyenne name Ho—my-ike (Beaver) until he was ten years old.

George grew up among dozens of different ethnicities and languages at Bent’s Fort. He could speak English, Cheyenne, French, Spanish, Arapaho, Kiowa, and Comanche fluently.

After Owl Woman died in 1847, George's father married her sister, Yellow Woman, according to Cheyenne custom. In 1853, George and his siblings were sent to a boarding school in Westport, Missouri that taught Native American children alongside white children. Their father wanted the children to have an education similar to other wealthy Americans.

George became friends with many young people from rich Southern families, but never really felt that he belonged to white American society. The school promoted the idea that white people, particularly Christians, were superior to other groups of people, including the Cheyenne.

In 1857, after completing his primary education, George was sent to St. Louis and placed in the care of Robert Campbell. Campbell was known for freeing his slave and taking numerous children of color under his wing. Under Campbell's care, George would begin attending Webster College.

George was seventeen when the Civil War started in 1861. In May of that year, Union troops were marching Confederate prisoners through the streets of St. Louis when shots were fired and the Union soldiers began firing into the crowd. Many were killed and the city was outraged. George and most of his friends at Webster College witnessed this and decided to join the Confederate army.

In 1862, George was captured by the Union army. He was required to swear an oath of allegiance to the Union and was then sent to a prisoner of war camp in St. Louis. He had only spent two days in the camp when Robert Campbell went to Union authorities and was able to get George released into the care of his brother, Robert. The two brothers rode together back to their home in Colorado. George had spent nearly a decade away.

Shortly after his return to Colorado, George became a member of Black Kettle’s Cheyenne tribe. Black Kettle was a famous chief who sought peace between Native Americans and white settlers.

George lived with his brother Charlie and Charlie’s mother Yellow Woman. Charlie had a reputation as a great warrior.

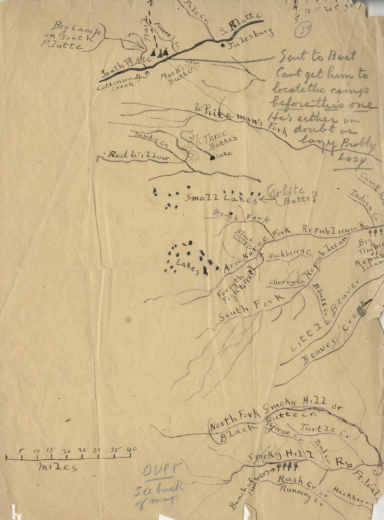

For many years, fights had broken out in Colorado over land the Native Americans owned, and that the United States wanted. Black Kettle wanted to put an end to the fighting. He gathered members of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes to negotiate peace with the United States.

George’s father William, an honorary Cheyenne chief, was an important part of these peace talks.

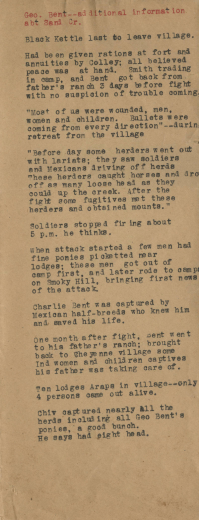

All the hopes for peace disappeared on November 29, 1864. That morning, the Colorado First Regiment attacked the mixed Cheyenne-Arapaho village at Sand Creek. The American soldiers had even forced George's brother Robert to lead them to the camp.

While some young men - including George and Charlie - were staying in the village during the peace talks, most occupants were women, children, and the elderly.

Anywhere between one hundred twenty and one hundred seventy Cheyenne and Arapaho were killed that day. The majority were unarmed.

George Bent became very angry after this betrayal by the United States. He renounced his ties to the US, and identified only with the Cheyenne tribe.

George and Charlie joined a band of Cheyenne warriors called the Dog Soldiers. The Dog Soldiers were the main force of Native American resistance against the United States.

The Dog Soldiers were known for their bravery. A Dog Soldier would tie himself to the ground during a fight, and could only be untied when the fight was won, or when all of his companions were safe.

After the Sand Creek Massacre, the Dog Soldiers went looking for revenge. They burned white villages, and cut off trading routes to and from Denver.

George was never a great fighter, but he participated in many Dog Soldier raids. At first George wanted to be part of the Dog Soldiers because they fought back after Sand Creek, but he started to worry that they were too violent.

In 1867, the United States attacked the Dog Soldiers in Summit Springs, Colorado. They killed most of the Dog Soldiers, including George's brother Charlie.

George agreed to act as an interpreter between the United States and the remaining Dog Soldiers after the battle. He hoped that talking would bring peace between the two groups.

The Americans were so impressed by George that they offered him a job as interpreter for the Indian Agent in charge of the Cheyenne and Arapaho tribes.

George began to take on other jobs for the United States Indian Agency as well. He never felt very happy working for the U.S. government. Many white people looked down on him for being half Cheyenne. The Native Americans did not fully trust George because he was half white.

When the Cheyenne and Arapaho were moved to reservations in Oklahoma, George moved with them. Many people disliked George after this. They thought George's translations tricked Native Americans out of their land.

George became very depressed. He saw that Cheyenne culture was disappearing. He wanted to make sure his people were remembered by history.

A famous anthropologist named George Grinnell also wanted to preserve the history of the Cheyenne.

He asked George for help translating while he interviewed tribal members. George was happy to help, and wanted to give even more information.

He wrote over four hundred letters to George Grinnell's assistant, George Hyde, about Cheyenne history and customs. He wanted to write a book about the Cheyenne before they were forgotten.

George Bent died during the 1918 Flu Pandemic. Before he died, he was able to see George Grinnell publish a book called The Fighting Cheyennes (1915), which he wrote with George Bent's help. In 1930, George Hyde sold the manuscript he had written from George Bent's letters to the Denver Public Library.

Many years later, the manuscript was published as a book called Life of George Bent Written from His Letters. These are two of the most important books about Cheyenne history.

George Bent's letters and translations helped make sure that the Cheyenne had their story told to history. Much of what we know about the Cheyenne during the 1800s is because of George Bent.

While he wasn't always successful, George followed in his parents footsteps to try to create peace between the United States and Native Americans.

oath of allegiance – when someone swears loyalty to a country

betrayal – to break trust or a contract

renounce – to formally abandon something

resistance – refusing to accept something or follow an order

interpreter – someone who translates between two or more languages

Indian Agent – a person who represented the United States government to Native American tribes

anthropologist – a person who studies human culture and societies

1918 Flu Pandemic – a very serious strain of the flu that spread throughout the world between 1918 and 1920. Around 500 million people died.

manuscript - a handwritten book or document

It was very hard for George Bent to feel like he belonged to either white or Cheyenne culture. Do you think people who are more than one race feel the same way today? Why or why not?

Why do you think people did not trust George Bent? Were they right not to trust him?

The Cheyenne once lived throughout Colorado, but they were not the only Native American tribe in the state. What tribe or tribes lived where you do today?

- If you don't know the answer, how would you find out?

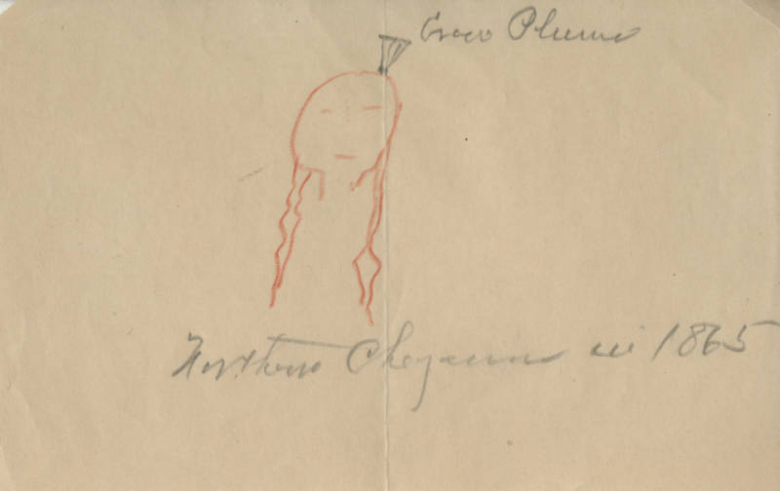

George Bent Manuscript Collection (Contains primary sources including drawings, maps, and the letters between George Bent and George Hyde. Also includes the original manuscript copy of Life of George Bent Written from His Letters. The George Bent collection can be seen in person on the 5th floor of the DPL Central Branch).

Biography Clipping Files (Newspaper, magazine, and journal articles about George Bent that can be seen in person on the 5th floor of the DPL Central Branch).

Books about George Bent at the Denver Public Library:

- Life of George Bent Written from His Letters (The history of the Cheyenne people, as well as the story of George's life with the Cheyenne including the Sand Creek Massacre).

- Halfbreed: The Remarkable True Story of George Bent (An adult-level book that is the first full biography written about George Bent).

- Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography (George Bent is listed in Volume I. The Encyclopedia of Frontier Biography can be viewed in person on the 5th floor of the DPL Central Branch).

Story of George Bent and the Sand Creek Massacre at the Kansas Historical Society

Interview about George Bent on Colorado Public Radio by the authors of Halfbreed: The Remarkable True Story of George Bent

Cheyenne Indian Fact Sheet for Kids

Cheyenne and the Bents were a

Cheyenne and the Bents were a great people.

He was a great man

He was a great man

George Bent was a Great

George Bent was a Great person fighter and interpreter.

I am half a world away, in

I am half a world away, in northern New South Wales, Australia, and I found this page during research for a novel. Thank you for the information herein; it has been helpful to me.

George Bent must have been a fascinating character. I would have liked to sit and talk with him, to listen to his experiences. To be caught between two worlds as he was must be a very difficult thing.

This article is full of

This article is full of errors. It even has the date of the Sand Creek massacre wrong.

Thank you for noticing the

Thank you for noticing the incorrect date. We have done some fact-checking and have added some clarifying details.I believe the date was likely a typo. Thank you for catching that for us.

cool :)

cool :)

good

good

thank you for the article and

thank you for the article and resources, the family goes back to 1638 sudbury N.E.

lots of interesting people

I have George Bents letters

I have George Bents letters he writes about the time he was little around 1839-1913.

Add new comment