It is said that there is no accounting for taste and that goes doubly for those delving into cannibalism. While you may be well-acquainted with the story of Alferd Packer, it is our pleasure to introduce to you a lesser known Colorado cannibal named Charles “Big Phil” Gardner.

Our tale begins on a winter evening in 1888 at the upscale Hotel Brunswick on 16th Street in Denver. Located between Lawrence and Larimer, men passed their evenings there in comfortable armchairs, smoking cigars and filling the hours with talk of business and nostalgia. This particular January evening, the hotel played host to an elderly, prodigal son in possession of a savory tale from Gold Rush-era Colorado.

The pale-looking man entered the smoky lounge and informed the gathering that he had not been back to Denver since leaving nearly forty years prior. He relayed an inventory of various famed acquaintances including John Poiselle, James Beckwourth and perhaps the most notorious of all, “Big Phil” aka Charles Gardner. He began to spin a yarn about a larger than life character who had broken a jailer’s back and crossed the frontier with a pair of disembodied legs.

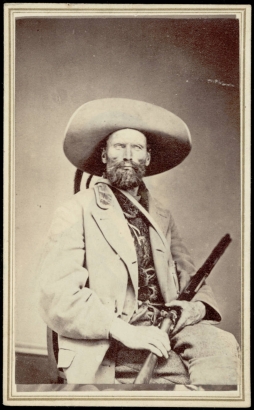

The elderly stranger described Big Phil as a six and a half feet tall man of 230 pounds and immense physical strength. Gardner was born in Philadelphia and was imprisoned for life after murdering someone during the 1844 riots in that city. Some claimed that he escaped after he broke his jailer’s back across his knee, while later accounts embellish to the point that he broke the jailer in half.

According to a January 3, 1887, article in the Rocky Mountain News, he attempted to meet up with a Mormon wagon train, but missed it by three days. While working to catch the train, he joined up with two army deserters near Fort Leavenworth. Having no money or provisions for the trip west, the trio decided to raid the home of a French Canadian trapper named La Chapelle. The three men broke into La Chapelle’s home at 3 a.m., demanding he reveal where his wealth was hidden. The Rocky Mountain News claims that Gardner cut the man’s ear off and threatened to stab him in the heart if he didn’t divulge the location of the money. The man turned over the $500, but died in the night anyway.

A group of vigilantes was then formed to seek out the desperados. Gardner managed to outpace his companions who were caught, killed and their bodies thrown into a fire. Gardner watched this ghastly scene from his hiding place until the vigilantes left. Having not eaten in some time, he crept towards the fire and took some roasted bits of his former companions to fuel his journey west. Thus Phil had his first cannibal feast. He eventually reached the Mormon train at Ash Hollow on the Platte River, where he was baptized a Latter-Day Saint.

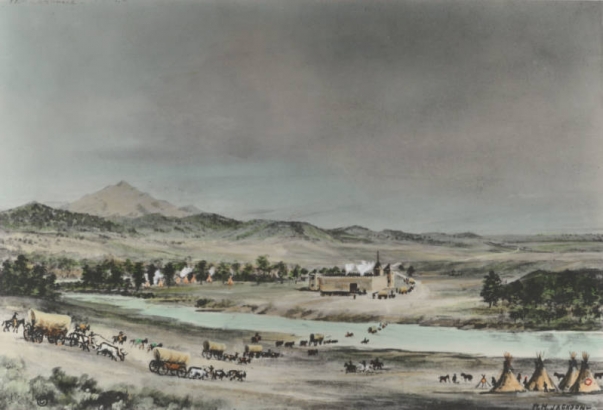

Our story picks up again with the recollections of famed Colorado pioneer and fellow Philadelphia native Edward Wynkoop, who met Gardner in the winter of 1858-1859, soon after Gardner began living in Colorado. Wynkoop found Gardner living with his two wives and several children in an Arapaho village on the South Platte River. Wynkoop recalled nothing but kindness and generosity from Gardner and recounted how he was welcomed into the lodge and given an abundance of food.

He did, however, also recount a story that Gardner told him about a job he took after arriving at Fort Laramie. General Harney sent him and a Native American guide to distribute dispatches to an army camp. Shortly after leaving the fort, the men found themselves in a terrible snowstorm. They lost their trail and their provisions and wandered for days. According to Gardner, he then caught his starving companion about to leap on him with a knife. A battle ensued and Gardner killed the man.

Gardner then ate his fill of the dead companion and packed out two legs for the journey. Upon arriving at his destination, he recounted the incident and displayed the legs stating, “And you see I have some provisions left.” Predictably, the legend grew and one apocryphal story even has him murdering and eating his Arapaho wife Klook to make it through a tough winter.

While Wynkoop found Big Phil to be a cordial and reliable friend for many years, William Byers told a different story. Byers, founder of the Rocky Mountain News, claimed that Gardner bragged about his cannibalism and had even informed him that he preferred feet and hands while considering the remainder of a corpse to be too gristly and tough. Like so many frontier stories, there is almost certainly truth at its core, but we will likely never be able to verify the facts around the edges. Likewise, there are many claims of Big Phil’s death, but none have been verified.

It was also claimed in a fraudulent memoir by “Capt. William F. Drannon” (nom de plume of one Mrs. Belle H. Drannon-Brown) that Gardner had ridden with Kit Carson. The saddest part of debunking this story (done by W. N. Bate in 1954) is the loss of a wonderful quote by Kit Carson telling Gardner, “if ever you and I are out together in the mountains and short of provisions, I will shoot you as I would a wolf.”

As we wind down the tale of “Big Phil” the cannibal, let’s return to the rapt audience in the sitting room of the Brunswick Hotel. When the elderly stranger from California finished his tale, the room fell silent. That silence was broken when General David J. Cook, Denver marshal and former general of the Colorado Militia spoke up.

General Cook declared, “I came across a case like that myself in ‘64.” During the course of many engagements during the Indian Wars, Cook’s men had found themselves without any meat for 30 days. When the hungry men came upon some “roasted Indians” lying beside some burned houses, Cook admitted that they had all eaten some and declared, “It was very good.”

Clearly, some inflation has been added to many of these stories, but equally clear is the relative commonality of this practice, especially in areas where nature is inhospitable. Likewise, while a serious taboo in most cultures, cannibalism also appears consistently throughout cultures and across time. While the earliest appearance of Big Phil occurs in an 1860 Rocky Mountain News article, his particular tale was neither the first such story nor will it be the last.

Comments

Hi, I'm not noticing

Hi, I'm not noticing citations other than a reference to the 1887 Rocky Mountain News article. Where are the Cook quotations and Byers story coming from? Thanks.

Excellent question. Most of

Excellent question! Most of the story comes from our wonderful clipping files. The Byers story comes from an extensive article written for Colorado Magazine by LeRoy Hafen in March of 1936. His section on Byers references notes that Byers attached to the Diary of George A. Jackson housed at the State Historical Society. The Cook quotation comes from an article in Field and Farm published on January 1, 1888. Thanks so much for your interest in this history and not being afraid to ask questions.

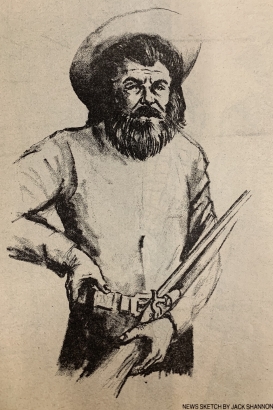

The drawing at the top says

The drawing at the top says it's from The Rocky Mountain News 1977. The Wild West Magazine I have says it's from 1877. Who is correct? The belt loops makes me think you're correct.

Well, Dave, you get the super

Well, Dave, you get the super-sleuth award of the day. I hadn't even noticed the belt loops. I just checked our clipping file on Phil and that image is from page 8 of the Rocky Mountain News August 29, 1977. The image also credits Jack Shannon who was a RMN artist and served as Denver Press Club president in 1979.

Thanks for the confirmation!

Thanks for the confirmation!

Thanks for being such an

Thanks for being such an engaged reader. We all appreciate it.

Add new comment