On Tuesday morning, Stephen Gillette set out on his route through Rocky Mountain National Park an hour earlier than usual. Mechanical issues meant that two of the A-1 Trash Co.’s trucks had been unable to make their rounds the preceding day, so he had set off before dawn to put a dent in the backlog. Around 6:15 in the morning, shortly after pulling into the Lawn Lake trailhead lot, he heard a roaring sound which he initially mistook for a jet about to crash. He realized his mistake when he looked for the source of the sound, but instead of seeing a jet he saw “…a ponderosa pine, limbs, bark and all, the whole thing, just sailing up, above the other trees…”.

He quickly backed toward the entrance, pulling his truck across the road to prevent a Michigan tourist from entering the lot. He exited the cab, racing to the emergency phone located at the trailhead entrance. Fortunately, the phone worked that day (it didn’t always), and at 6:26 the Park Service dispatcher heard Gillette, yelling to be heard over the sound of the roar, saying “A lake, a dam – something’s flooding!” After identifying himself, he informed the dispatcher that he’d barricade the road while waiting for the rangers to arrive.

Two park rangers arrived shortly, and within minutes of each other. The three quickly set about locking the Fall River Road gate, and barricading Horseshoe Park Road. By the time those tasks were completed, they were standing in rushing, muddy water up to their knees. It was clear to the Park Service that they were dealing with an emergency, but they didn’t yet know what exactly the emergency was, nor how severe.

As it happened, the source of the problem was the Lawn Lake Dam. The dam was most likely constructed in 1903, and had been expanded in 1931 to increase its capacity. Over the years, the makeshift road which had been built to aid in the dam’s construction had all but eroded away. By 1975, inspectors were forced to hike six miles each way in order to view the earthen dam. In 1975, the inspector recommended a more thorough examination once the snow melted, and in both '77 and '78, the dam was categorized as being in “fair” condition, and possibly in need of repair. Due in part to its inaccessible nature, no comprehensive examinations were done, and no repairs were made.

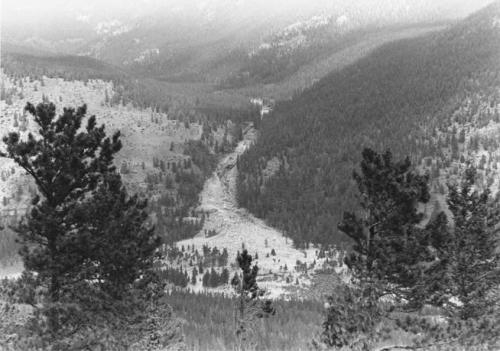

Shortly after 6 a.m. on July 15, 1982, the Lawn Lake Dam underwent a catastrophic failure, and for a brief period the Roaring River let the world know how it got its name. 30 million cubic feet of water tore through the landscape, ripping trees out by their roots, and sweeping tons of boulders and other debris along in its passing. Upon reaching the mouth of the valley at Horseshoe Park, where the torrent was able to spread out and slow for a bit, it left an alluvial fan covering over 40 acres.

That still wasn’t the end of it. Much of the water, mud and detritus rushed across the Horseshoe Park basin, merging with Fall River and backing up behind the Cascade Dam. Fortunately, this dam was able to withstand the added pressure, but the sheer volume meant that the dam was quickly overtopped, causing a secondary flood surge. Fortunately, much of the debris remained behind the dam, as this resultant swell poured through the town of Estes Park.

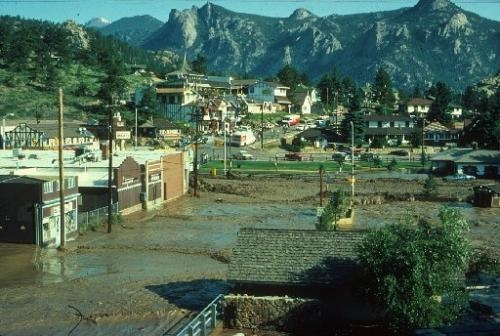

Floodwaters in the town reached between five and six feet in depth, and left two feet of thick mud in its wake as it hurtled through the town, joining the Big Thompson river on the far side. Elkhorn Avenue, Estes Park’s primary commercial strip, roughly paralleled Fall River, and sustained the bulk of the damage. When all was said and done, the flood did over 31 million dollars in damage to Estes Park alone, most of which wasn’t covered by insurance.

All things considered, it could have been significantly worse. Despite the event’s magnitude and force, only three people lost their lives; a lone hiker who had camped near the banks of the Roaring River (and who likely never knew what hit him), and a couple who returned to their campsite below the Cascade Dam, shortly before it overtopped. Given that the campground had been evacuated by the Park Service, it’s highly likely that the death toll would have been much higher if Stephen Gillette hadn’t set out on his route an hour earlier than usual that day.

For more information on this, or other historic Colorado floods, visit Western History and Genealogy. Don't forget to like our Facebook page to keep up to date with all our research news and events!

References

Comments

Chris, thank you for this

Chris, thank you for this short but informative story on the Lawn Lake Flood. When I heard the news in Vail, it reminded me of the Big Thompson Flood of 1976, the summer we moved from the midwest to Vail.

I remember all of the news on TV and reading accounts in the Denver Post and Rocky Mountain News.

Floods are an interest I have given our unusual weather patterns that can change in minutes.

Thanks for your interest, and

Thanks for your interest, and your comment, Mike. Colorado has certainly had no shortage of floods over the years.

I remember very well the…

I remember very well the flood of '76, and thought of it as I read Chris' story about the Long Lake flood. Similarities -- both floods roared through fairly narrow rivers (Fall River and the Big Thompson). Both scoured their canyons free of rocks, trees, and sadly, people. Differences -- The dam blew out on Lawn Lake, but Olympus Dam on Lake Estes held out. If Olympus Dam had blown out, town of Loveland would likely have been destroyed. The deaths from the Long Lake flood were sad, of course. Roughly 10 times the number of deaths from the Long Lake flood occurred in the Big Thompson flood. Both floods left permanent damage, a sad but useful learning experience to remind us of the overwhelming power of nature. One can still see the alluvial fan left from the Long Lake flood, and driving through the Big Thompson Canyon one can still see reminders of the '76 flood (and the later Big Thompson flood, of course). I would give almost anything to live in the mountains again -- but just not in a canyon.

We camped at Lawn Lake in the

We camped at Lawn Lake in the 60's to fish. There was a cabin the CCC built in the 30's in which we stayed. We fished 2 or 3 days. My brother and sister and I were guided by a family friend (Cecil Hinshaw) who also took us up Longs Peak via the cable route on the North Face now a technical route after the removal of the cables.

Was there that day, camping…

Was there that day, camping in the backwoods about 6 miles up from the public campground. The sound woke the three of us up - hangovers instantly gone. As it got closer the sound was deafening - you couldn't hear yourself scream if you wanted to. In the twilight the site was surreal as mature pine trees were bobbing through the air on what we quickly determined was a massive wall of muddy water. Water spray and splashes on our site sent us scurrying for higher ground. After its main pass, we spent hours watching tons of earth and 100' trees fall into the newly formed canyon edges. The canyon had to be a football field across with shear drop edges. We had a transistor radio but couldn't find any reports on what was happening. A few hours later a rescue group found us on the other side of the canyon and with their body gestures we figured out they wanted us to stay there! A couple more hours passed, the rescue group reached us, gathered us, and then scrambled us to an open site where helicopters transported us and our gear to the ranger station for interviews. Once in the air, the devastation was evident, especially over the public campground. Initially we were thinking of setting up tents closer to the 'creek' but decided to set a can of peaches in the water and camp higher up at the designated camping spot. It was a wise decision, we would have been goners like our can of peaches. As it was, our tents ended up to be about 20' from the newly formed canyon edge. Afterwards we were put up at a commercial campground outside the park. There were 7 or 8 other guys that were also 'rescued' from our area who were put up at the campground. Turns out all of us were from IL. Hopefully not bad juju. It was an unforgettable and solemn experience for three novice backpackers from Chicago.

Add new comment