“There are those who aim to make merchandise of these beautiful specimens, to fence in these rare wonders, so as to charge visitors a fee, as is now done at Niagara Falls.” - Ferdinand Hayden’s prophetic warning to the US Congress and President Ulysses S. Grant - 1876

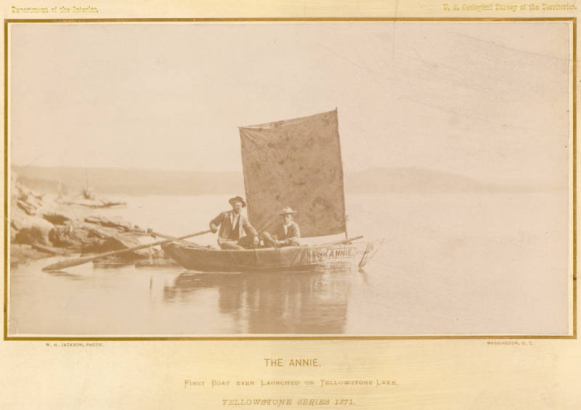

The first documented instance of a boat being launched on Yellowstone Lake was a small, rickety craft named “Annie.” The boat, which used a tent-fly as a makeshift sail, carried a couple representatives of the Hayden survey team, as part of the work of the U.S. Geological Survey of the Territories. In honor of the work Hayden and his team performed, a large swath of the park was named the “Hayden Valley.”

No such tribute exists for E.C. Waters and his contributions to Yellowstone. His legacy is limited to some waterlogged wood and rusted iron of his namesake, slowly decaying where it washed up on the shore of Stevenson Island.

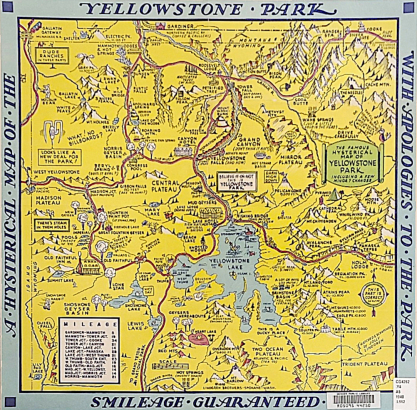

In March of 1872, when President Ulysses Grant signed the “Act of Dedication” formalizing the creation of Yellowstone National Park, few people grasped the significance of the event. It would be years before Yellowstone’s potential as a tourist destination would be recognized, and in the early years it was far too remote and inaccessible to draw much of a crowd. That would soon change, as multiple hotels were built within the park, and the Northern Pacific Railroad laid a route to Gardiner, Montana, just outside the park’s northern border.

In 1887, Ela Collins Waters (E.C.) was hired to run the Yellowstone Park Association (YPA). The YPA was an organization formed by Northern Pacific investors to manage hotels, and make the park more appealing to tourists. Waters was a civil war veteran, local politician, and an entrepreneur, and was the first person to turn a profit off of the park’s natural resources. He also had a reputation for being abrasive, cantankerous, and greedy, and those qualities would be on full display before his tenure at the park ended.

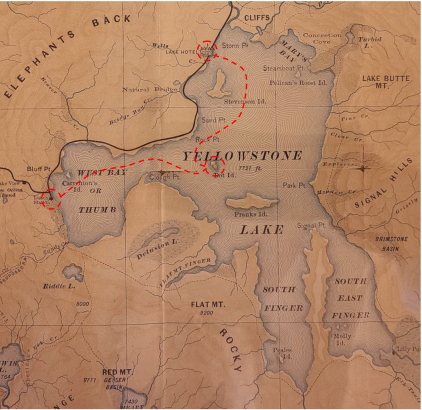

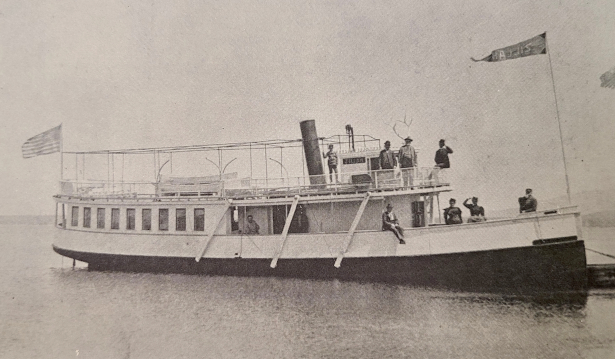

Even with the nearby rail station, travel to Yellowstone proper, as well as within the park, relied on long, usually uncomfortable stagecoach rides. Believing that people would be willing to shell out a little extra money for a more comfortable ride toward the end of the journey, Waters had a small steamboat shipped to the park by rail and wagon. The ship arrived from Lake Minnetonka, Minnesota, in three pieces. The ship had to be reassembled at the West Thumb bay dock of Yellowstone Lake. Waters managed to negotiate a good deal on the ship (officially named “Clyde,” but nicknamed “The Useless”), owing to the fact that it had been poorly constructed: it listed heavily to starboard, had a too-loud whistle described as an “ear-piercing shriek,” and its speed topped out at a measly 16 miles per hour.

Nevertheless, the ship was functional enough for Waters to found the Yellowstone Lake Boat Company in 1889. The ship, now christened “Zillah,” in honor of the railroad president’s daughter, shuttled travelers from West Thumb to the Lake Hotel on the northern shore of the lake. Sources disagree on the exact fare amount, but passengers were charged either $2.50 to $3.00 for the trip, reportedly with $0.50 per ticket being kicked back to the coach drivers, as a tacit “thank you” for the upsell. That works out to roughly $80 to $100 per ticket in today’s dollars, with the kickback amounting to around $17 per passenger. Given that the Zillah carried 125 passengers, even at the lower of the 2 reported ticket prices, and taking into account the money passed on to the coachmen, each boatload earned Waters around $250 (a bit over $8250 today).

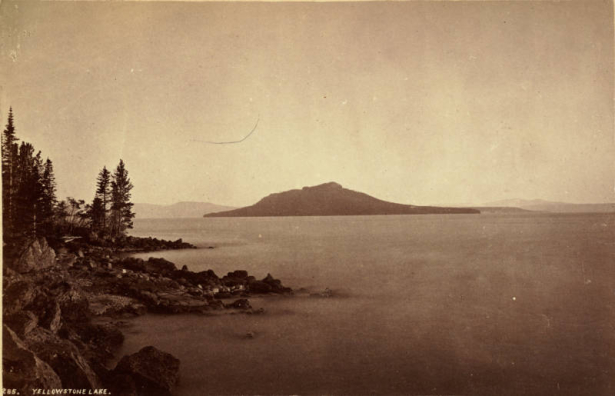

Unsatisfied with the apparent success of the shuttle service, Waters had bigger plans. One of the draws of Yellowstone (then, as now) was wildlife. Due to the fact that much of the park remained completely undeveloped, animal sightings weren’t as commonplace as they are today. Waters wanted to capitalize on the public’s desire to see wildlife, so in 1896 he constructed a makeshift zoo, or “game show,” on a small island between West Thumb and the hotel. The island was so small that the Hayden survey had named it “Dot Island,” as it was little more than a dot on the map.

The zoo was composed of animals already found within the park, primarily bison and elk. At the beginning of the zoo endeavor , the animals were treated well, and were removed from Dot Island and housed and fed onshore throughout winter months. As time passed, however, the zoo fell into disrepair, and the animals were neglected, leading some visitors to complain about them being malnourished to the point of starvation. In addition to the egregious treatment of the animals, Waters exploited the tourists as well.

Despite the fact that both the ferry service and the zoo had proven lucrative, Waters wanted more. The next logical step would be to acquire a larger vessel, so he could shuttle more passengers, and that was something he was keen to do. In the interim, however, he implemented a far more ethically questionable scheme. Upon boarding the Zillah at the West Thumb docks, the passengers were informed that they would be making a stop at Dot Island, and that they were welcome to see the “game show.” Once they had seen the animals, and were looking to re-board the ship, they would be informed that their tickets had only covered passage from the dock to the hotel, and that they were required to pay an additional fee for the visit to the zoo.

As might be expected, this scheme didn’t go over well. Waters had already been on the receiving end of quite a bit of animosity, owing to his abrasive personality, as well as his past behavior. Years earlier he had been arrested and briefly banned from the park for “soaping” a geyser (throwing soap in a geyser causes a chemical reaction that induces eruptions). His status was quickly reinstated due to his friendship with Russell Harrison, son of the future president Benjamin Harrison. He had also fought tooth and nail to remain the exclusive boat company allowed to operate within the park, despite many aspirational vendors feeling that competition would be beneficial.

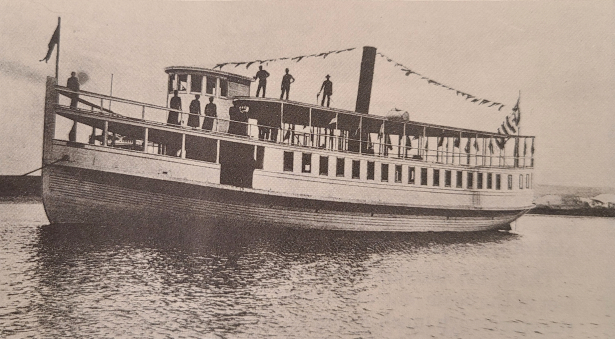

Exploiting park goers was the final straw. By 1905, the Zillah had fallen into disrepair, and potential passengers were concerned that it was no longer seaworthy (lakeworthy?). Waters had commissioned a significantly larger steamship capable of carrying 500 passengers, and had arranged for its delivery and assembly. As a testament to his own ego, Waters christened the new ship the “E.C. Waters.” His opponents within Park Administration, however, finally had some leverage over him with this request. They refused to grant him a license to use the new vessel, limiting the number of passengers allowed to no more than could fit on the Zillah (125). This limit outraged Waters, but he was impotent to force the issue. Throughout the dispute, the new vessel remained docked save for a few unoccupied trial runs. As further insult to Waters, in 1907 the Zillah was deemed unsafe, and was presumably scuttled (though the exact location of the remains is unknown).

Waters continued fighting for the right to operate his new ship at capacity, but the powers that be had had enough of him. In 1907 the park administration revoked his license to operate within Yellowstone at all, with the Yellowstone National Park Superintendent Samuel Young making the following declaration:

"E.C. Waters, president of the Yellowstone Lake Boat Company, having rendered himself obnoxious during the season of 1907, is, under the provisions of paragraph 11, Rules and Regulations of the Yellowstone National Park, debarred from the park and will not be allowed to return without permission in writing from the Secretary of the Interior or the superintendent of the park."

Needless to say, the requisite permission was never granted. The E.C. Waters ship was berthed on the lake in a cove at Stevenson Island, and in 1921, the abandoned ship was driven up on shore in a storm. The wreck was salvaged for parts (for example, the ship’s boiler was used to heat the Lake Hotel for nearly 50 years). All that remains at this point is the waterlogged wood and rusted iron of E.C. Waters’ namesake, slowly decaying where it washed up on the shore of Stevenson Island.

Visit the Special Collections and Archives for more, and join our fans on our Facebook page!

Sources used:

2- Selling Yellowstone: Capitalism and the Construction of Nature

3- Yellowstone: The Creation and Selling of an American Landscape 1870-1903

4- The Yellowstone Story: A History of Our First National Park vol.2

Comments

Nicely written and narrated!…

Nicely written and narrated!

Thank you!

Add new comment