Daniel C. Burns, chairman of the Prohibition Party’s State Executive Committee defended the party's choice to nominate only female candidates in a letter to the editor published in the Rocky Mountain News on March 25, 1901:

You ask “Is it equal for a ticket to be composed of women only?” I answer no. It only tends towards equality. If all the tickets up for the next 100 years are composed solely of women the fair sex would only have a start towards equality and evening up of the past centuries that man has ruled alone and with a tyrannical hand.

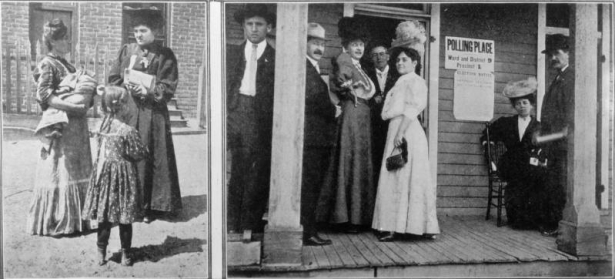

None of the women won their seat in the April 1901 Denver election, including Antoinette Hawley.

But it’s important to note that Hawley didn’t come in dead last, either. Garnering 456 votes, she edged out fourth place mayoral contender J. W. Martin, candidate for the Socialist Party, by 215 votes.

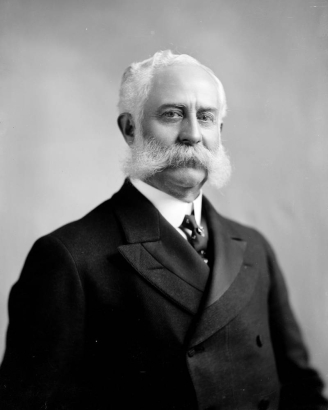

It was Republican Robert R. Wright, Jr., former owner of Skinner Bros. & Wright Bros. department store, who overtook the Democratic Party's candidate E. T. Wells and won the mayoral election.

(Denver didn't adopt run-off mayoral elections until 1952.)

WHO WAS SHE?

Antoinette Arnold Hawley's biography has largely been confined until now to a handful of paragraphs in temperance histories.

Hawley was best known for her leadership in the Women's Christian Temperance Union (WCTU) and writing the organization's "Crusade Glory Song." She was active in WCTU chapters in Minnesota, Iowa, Missouri, and Colorado. From 1899 to 1905, she reigned as president of the Colorado WCTU.

In addition to promoting temperance, the WCTU also played a significant role in advocating for women's rights. Many of the organization's leaders fought for women's right to vote and social reforms — which Hawley did as well, particularly in the final decade of her life.

As the Denver Post said of Hawley in her August 13, 1919 obituary:

For many years, no movement looking toward the betterment of human conditions and civic affairs lacked the enthusiastic support of Mrs. Hawley.

Antoinette Hawley, however, was more than just her WCTU involvement and her 1901 mayoral campaign. Using genealogy and newspaper databases, I was able cobble together a fuller story of the woman she was.

Early Life

Antoinette Arnold was born on January 23, 1843, in Rochester, New York. According to the 1865 New York state census, her mother, Sarah Maria Babcock Arnold (1812-1883), was a sick nurse; her father, Smith. H. Arnold (1792-1866), a patternmaker.

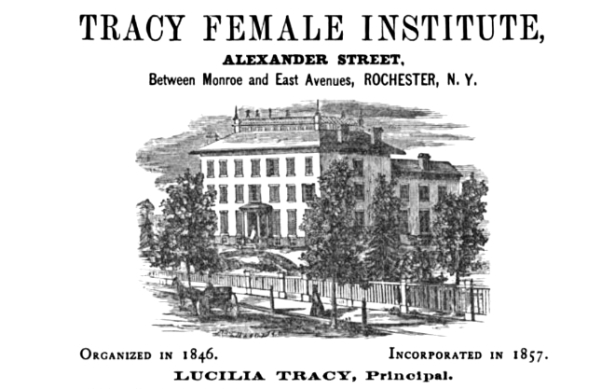

Antoinette was educated in private schools and graduated from Rochester's Tracy Institute in 1864. A year after graduation, she made her way to Michigan and taught school. The 1870 U.S. census shows her living in Bruce, Michigan.

Marriage

Antoinette married James A. Elgan in Sangamon County, Illinois, on April 21, 1874. The couple had two children together: Sylvia Sarah (born 1875) and Paul Brewster (born 1879).

The Elgan family moved from Pana, Illinois, to Minneapolis, Minnesota, around 1878. The 1878 city directory lists James Elgan as a carpenter; the April 22, 1878, issue of the Star Tribune documents Antoinette serving as corresponding secretary of the Women's Christian Temperance Union of Minneapolis. She was also active in the Hennepin Avenue Methodist Episcopal Church.

A Period of Profound Loss

On April 28, 1880, a fire destroyed the Elgan, Simms & Co. planing mill and sash factory in St. Paul, which was partially owned by James Elgan. Losses from the fire totaled $11,000 and the company dissolved within a few days.

But the Elgan family's troubles didn't end there.

Both Elgan children contracted diphtheria, and on May 5, daughter Sylvia died a few weeks before her fifth birthday.

Then on May 9, the Saint Paul Globe reported the following:

James Elgan, one of the firm of Elgian [sic], Sims [sic] & Alison, whose sash door and blind factory was recently burned in St. Paul, has suddenly left for parts unknown after having swindled a number of parties out of various sums ranging from $5 to $270. He leaves a family in Minneapolis.

An article entitled "Elgan's Escapade" appeared in the Star Tribune just a few days later and elaborated on what they deemed James Elgan's "series of deceits." It was revealed that during his two years in Minneapolis, James had managed to hide from colleagues and friends that he was married with two children. As such, it was believed that he had,

followed to Honolulu the wife of one of the employes [sic] of the late firm with which he was connected....

Then, on May 18, the couple's son, Paul, died from diphtheria just before his first birthday.

Antoinette had lost her daughter, son, and marriage — all within the span of two weeks.

"We turn, for peace, to nature and to God"

On July 10, 1880, the Minneapolis Journal published a poem written by Antoinette called "Afterward." The poem begins with the words

When, from our lives, slips every cherished good,

As from a baby's hand, the treasure'd sweet, —

When all our idols, gold or clay, or wood,

Break, crumble into ashes at our feet....

The poem describes the tremendous loss Antoinette had suffered, but also the solace she found in her religious faith.

Printed just a few pages from the poem was a notice of Antoinette's filing of a decree of divorce from James Elgan "upon the ground of adultery, desertion and cruel treatment." A divorce decree was granted in 1881. The February 1, 1881, issue of The Saint Paul Globe stated that "the decree was issued on the ground that the defendant had been living with Mrs. Jennie King the last year."

Biographical sketches of Antoinette would never reveal that she divorced from James Elgan, and instead stated she was widowed.

A New Start

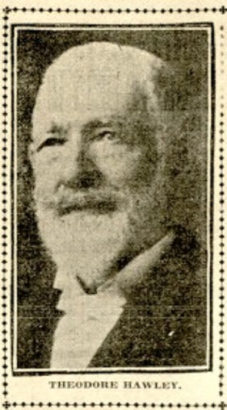

Antoinette went on to marry Theodore Hawley (1827-1911) in Romeo, Michigan, on October 24, 1883. He was an attorney in Fort Dodge, Iowa, who had served as an Iowa state senator from 1868 to 1871.

The couple resided in Iowa and Antoinette once again became involved with the WCTU. By January 1887, Antoinette was serving as vice president of the Iowa WCTU's 10th District.

Around 1889, Theodore established the law firm Hawley & Snell in Kansas City, Missouri, and the couple moved. Antoinette went on to serve as president of the Missouri WCTU's 12th District.

Colorado

The Hawleys moved to Denver in 1893. The following year, Antoinette was elected president of the Central chapter of the WCTU in Denver. In 1899, she was elected president of the Colorado WCTU — a post she held for five years.

Antoinette remained active in the WCTU after her term ended. Known for her eloquent writing, she for many years reported on Colorado in the organization’s national journal, The Union Signal. Antoinette was also a strong orator, and there are dozens of Colorado newspaper accounts of Antoinette’s speeches and lectures. While she was most active in the WCTU, she also participated in the Woman’s Club and the Daughters of the American Revolution (DAR).

Antoinette’s involvement in politics continued past the 1901 Denver election. She ran as the Prohibition Party candidate for Regent of the State University in 1906 and 1910, without success.

A Rebirth (of sorts)

In 1911, Antoinette's husband Theodore died. And so did Antoinette — or at least the Denver News thought so. The story spread quickly throughout the state, until Antoinette Hawley herself heard about her supposed demise.

Recognizing their serious error, the Denver News printed a statement on July 6, 1911:

Through an error in the transmission of names, The News published a report of the death of Mrs. Antoinette A. Hawley in its columns yesterday morning. It was Mrs. Jennie D. Hawley, wife of A. M. Hawley, who died.

Antoinette Hawley is reported to have said to the News editor,

Now, I don't insist on a retraction...but I would like a birth notice.

Women's Rights, Labor Rights

Hawley didn't slow down in her twilight years.

On March 20, 1911, she was one of the 200 women present at the state capitol when a bill ensuring that women and girls would not labor in factories and similar institutions for more than eight hours a day passed in the Colorado state senate.

After the Ludlow Massacre on April 20, 1914, Hawley joined "a mass meeting" held in the Colorado House of Representatives chamber and gave a speech in support of devising "ways and means of helping the women and children in distress in the strike district." (Denver Post, April 23, 1914).

In 1915, Hawley fell at Denver's First National Bank and fractured her hip. The Denver Post reported on April 3 that she was critically, and on April 5, that she would never walk again

When Colorado's state prohibition of alcohol went into effect on January 1, 1916, Hawley was alive and well. She resumed club involvement and speaking engagements, until on November 24, 1917, she was thrown to the pavement and severely injured while trying to board a Denver streetcar.

Despite her health struggles, she was one of the senders of the following telegram to Senator John F. Shafroth (Colorado-D) on March 31, 1918:

Democracy must be realized in deeds, not words. Twenty million women are waiting the action of the Senate for justice and freedom in our Nation. We regret the delay and believe that the immediate passage of the Federal suffrage amendment will speak for freedom throughout the world.

Antoinette Arnold Hawley died at the age of 76 on August 12, 1919, at a sanitarium in Boulder, Colorado. She is buried in Oakland Cemetery in Fort Dodge, Iowa.

Comments

For Katie Rudolph

For Katie Rudolph

Katie,

This blog on Antoinette Hawley is excellent. I would love for you to submit it to the Colorado Encyclopedia. It would be an important addition to the many articles on women that we have amassed.

Please get hold of the Encyclopedia to get guidelines at https://coloradoencyclopedia.org/

Regards, Rebecca

Add new comment