Many Coloradans will mark Earth Day by getting out to enjoy the beautiful, natural places spread far and wide across our state. Some of these outdoor enthusiasts will take advantage of the Colorado Trail, a hiking path that spans 567 miles across Colorado’s central mountains, crossing eight mountain ranges from Denver to Durango. The Trail was constructed almost entirely by volunteer hands between 1974 and 2000. It has had a profound impact on how Coloradans and tourists alike enjoy the outdoors, allowing hikers, mountain bikers, horseback riders, and cross-country skiers increased access to the natural beauty of our mountains.

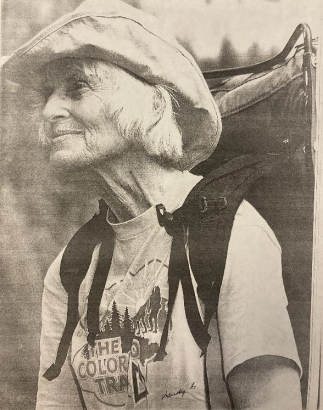

One charismatic woman was the Trail's primary driving force, and she saw the project through to completion over a course of twenty-five years. Gudrun “Gudy” Gaskill’s infectious enthusiasm for the outdoors helped in her negotiations with U.S. Forest Service officials and private property owners, and with mobilizing thousands of volunteers each summer. In addition to handling logistics – mapping, fundraising, planning, aka the “office work"– she also helped with the dirty work – digging, setting up camp, and getting up early to keep the trail-building crews motivated and fed.

Gaskill’s strength of character and persistence challenged norms for women of her generation. She also overturned expectations that older adults will slow down as they age. Gaskill’s story is intertwined with the Colorado Trail, and her work was a great gift to the people of Colorado. Her papers were recently donated to the Denver Public Library, and are now open to all researchers.

Gudy Gaskill, Outdoorswoman

Born in 1927 in the small town of Palatine, Illinois (now a suburb of Chicago), Gudrun Timmerhaus, known by many as “Gudy,” was drawn to sports at a young age. She participated in downhill and cross-country ski races at local Illinois ski hills, but really discovered her passion for the outdoors during childhood summers spent in Colorado. In her early teen years, the Timmerhaus family moved to Colorado for several summers, when their father served as a volunteer ranger naturalist at Rocky Mountain National Park. Each morning on his way into work, Mr. Timmerhaus would drop Gudy and her siblings off at a trailhead with water and a watch, and tell them to be back from their hike when he returned later that afternoon. This freedom to explore nature unattended surely contributed to her early love for the great outdoors.

As young Gudy Timmerhaus reached college age in 1944, she chose Western State College in Gunnison, partially drawn by a brochure advertising the school’s famed ski run, illuminated at night to extend the hours for skiing. While pursuing a degree in Education, she also met her future husband, David Gaskill. Their 1948 marriage was somewhat unusual for the time, as indicated in a 1989 Up the Creek interview with her,

“When we were married, before women’s lib, I was already mountain climbing, and he [Dave] gave me a written contract that I could do anything I wanted to do.”

Following graduation, the Gaskills set off across several years of adventures, pursuing work and graduate education in Kansas, Colorado, New Mexico, and California, before finally settling for good in Golden, Colorado. During that time, Gudy Gaskill completed a master’s degree in Industrial Recreation at the University of New Mexico, and they began their family of four children. Gaskill would eventually establish her own real estate business in 1974.

After returning to Colorado in the early 1950s, the Gaskills joined the Colorado Mountain Club (CMC), and Gudy quickly became an active leader of local hikes and international treks. She served on the Huts and Trails Committee, and in 1977 became the first woman president of the CMC.

To Build or Not to Build: Environmental Controversy & The Trail to Nowhere

It’s hard to imagine today, but the idea of the Colorado Trail was met with some controversy when it was first proposed. In the early 1970s, a U.S. Forest Service official called together various environmental organizations to propose building a public recreation trail across Colorado that would be similar in concept to the Appalachian Trail. Gaskill attended the meeting as a representative of the CMC. Not all attendees were as enthusiastic as Gaskill about a trail: some of the organizational representatives present opposed the project due to fears that increased public access would have a negative impact on the wilderness.

As Colorado has grown in population and begun experiencing overuse and abuse of popular hiking destinations, we see the environmental groups’ fears were not entirely unfounded. Building a trail that leads from cities directly into the wilderness gives inexperienced hikers easy access to the backcountry, resulting in a heightened potential for negative ecological impact.

Proponents of the trail idea, however, argued that increased exposure to Colorado’s mountains would build respect for nature – something that had been lacking in much of the state, where trash and abandoned mine tailings were not an uncommon sight at the time the trail was proposed. The trail proponents argued that increased natural recreation would enhance public support for environmental protections and programs. Gaskill’s son Steven summarized her thinking in a recent KUNC radio story,

“You know, if you want to save wilderness, No. 1 you have to have people that understand it and have seen it, so they'll fight for it….then she said, 'No. 2, if I build a trail, people will use the trail and that will be a corridor where people will see the wilderness, and the rest of the wilderness will stay wilderness.'”

As an added pro-building argument, proponents knew that a trail could bolster Colorado’s tourism, at a time when the ski industry was still in its early years of development. Another goal that certainly must have been top of mind for Gaskill, were the intangible benefits outdoor recreation provides for the health and psyches of humans.

Despite early debates, in 1974 the pro-Trail camp was successful in forming the Colorado Mountain Trails Foundation, launched with a $50,000 Gates Foundation grant. The organization mistakenly assumed they’d be able to stitch together roads shown on historic maps and complete the trail in time for Colorado’s Centennial celebration in 1976. Gaskill participated in drawing a new detailed route through Forest Service districts, stitching together existing, inactive, and nascent park trails with long neglected mining and logging roads.

The Colorado Mountain Trails Foundation quickly discovered, however, that, after decades of neglect, many of the trails on the map were trails in name only, while in actuality were entirely overgrown or washed out. Another challenge that arose was that the organization’s operational costs soon ate through the bulk of their grant funding. Needless to say, the Trail was not completed in time for the 1976 state centennial, nor for many years to come.

The trail clearing and construction work itself would take nearly two hard-working decades to complete, leading Denver Post critic Ed Quillen in 1984 to dub the project the “Trail to Nowhere”.

Shovels, Picks, Saws and….Pancakes? Building the Trail

As the Colorado Mountain Trails Foundation project began to founder, Gaskill stepped up to breathe life back into the project. Despite public concerns, budget challenges, and some media sniping, her persistence and devotion to the project continued. Over the years she negotiated with federal agencies and private property owners to gain support, including persuading reluctant district forest managers to facilitate the project. Without consistent and sustainable funding for trail construction, the new Colorado Trail Foundation staff realized it would have to be built entirely by volunteers.

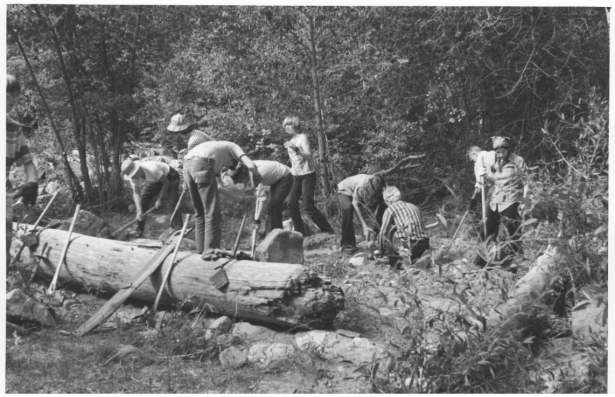

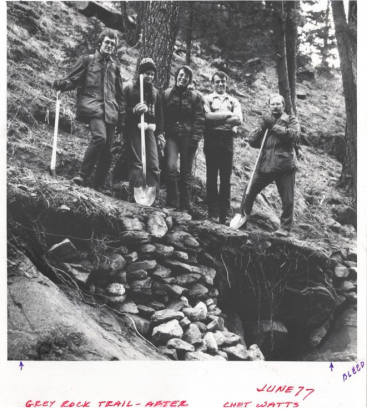

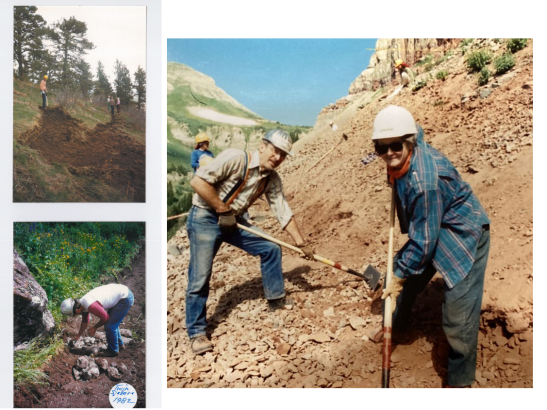

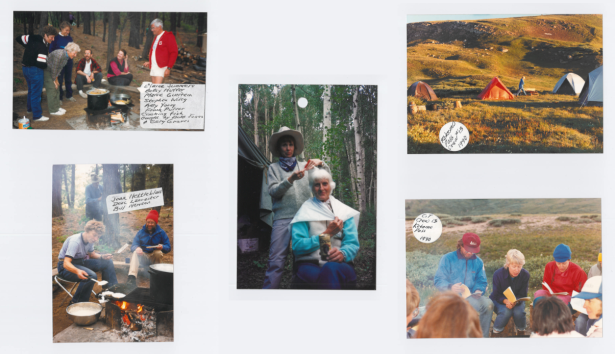

Summer after summer, Gaskill recruited new crews, largely by word of mouth, for weeklong projects camping and working in remote wilderness areas. The Colorado Mountain Club and Colorado Trail Foundation usually provided funding for food, and for many years tools were borrowed from various sources, or provided by volunteers themselves.

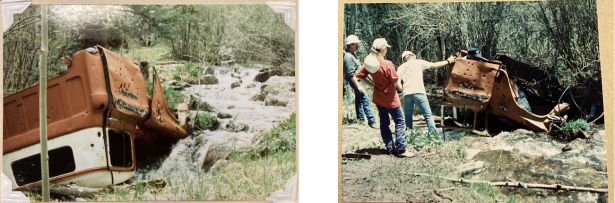

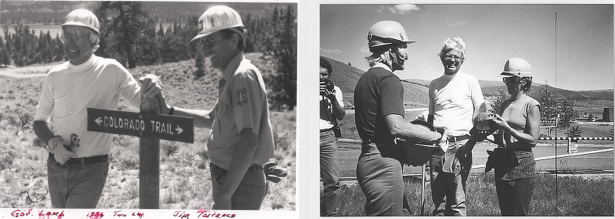

Project crews ranged in size from ten to twenty volunteers, and the number of crews each summer could vary anywhere between three to forty-five. These volunteers contributed their time and sweat equity to clearing and digging trails. They removed trees, stumps, and rocks; carted out garbage as large as the 1957 GMC truck they found abandoned in a mountain stream; and they built occasional benches and bridges over streams. A 1985 trail crew even included then-Governor Dick Lamm on a team working in the Twin Lakes area.

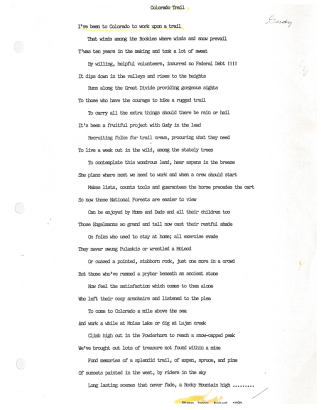

For the volunteers, this work was a labor of love. Many crew members built lifelong friendships through these weeklong “vacation” projects, and as is documented in the collection, many continued to correspond with Gaskill for years after their crew experiences. Trail work was hard physical labor, but volunteers managed to enjoy themselves as well. Each crew fostered their own culture, with poems, stories, jokes, on-trail birthday parties, and even a Colorado Trail song being shared over the years.

Coming together, segment by segment, the first 480 miles of the Trail (approximately 80% of the final distance) were finally dedicated on July 23, 1988. Following this success, for several years Gaskill and volunteers continued to replace road-based sections with off-road routes through more scenic areas. Gaskill also turned to ongoing maintenance of the trails, bridges, and shelters along the route. While the Colorado Trail continued to grow in pieces and be refined over time, Gaskill herself considered the project completed in 2000, when all trail signage was finally in place.

Gaskill’s decades of dedication to the Trail were acknowledged both locally and nationally, by President Ronald Reagan in his 1987 “Take Pride in America” campaign, and by President George Bush in his 1991 “One Thousand Points of Light” program (Gaskill was #204). In 1989, the City and County of Denver declared February 28, 1989, “Gudy Gaskill Day;” and in 2002, she was inducted into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame. Posthumously, the Colorado legislature and Governor John Hickenlooper declared March 20, 2017, “Gudy Gaskill Day” in Colorado.

In her earlier years, Gaskill’s life had challenged traditional gender roles common for her generation, and in her later years she also refused to be limited by stereotypes about age. Gaskill continued participating in winter sporting events into her seventies, placing in the Senior Winter Games and Rocky Mountain Senior Games for sports such as snowshoe, ice skating, and ski slalom. In a 2008 interview recorded by the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame when Gaskill was 80 years old, she proudly stated she had adventure packing down to an art, managing to successfully pack only eighteen pounds for a weeklong hiking trip. That seems like a worthwhile life goal to most backcountry hikers.

On July 14, 2016, Gudrun Gaskill died following a stroke. The legacy she left behind continues to inspire and enrich the lives of Coloradans and tourists, and will for generations to come. As tourism has turned into a multimillion dollar industry, and Colorado’s population has exploded, the Trail remains a peaceful refuge for many.

Happy Earth Day to those of you out on trail!

---------------------------------------------

Sources Cited:

- Gudrun "Gudy" Gaskill Papers, CONS277, Western History Collection, The Denver Public Library.

- Colorado Trail Foundation

- Gudrun "Gudy" Gaskill, Colorado Women's Hall of Fame

- Mother of the Colorado Trail Highlighted in New Archive, KUNC

Other related resources:

Comments

Wonderful article about an

Wonderful article about an inspiring, energetic, trailblazer, heroine!

Thanks for reading Vicky, and

Thanks for reading Vicky, and yes, I agree! Processing her papers, I was impressed at her choice to tackle life's challenges with a good attitude. Inspiration for us all!

Thanks for this article. I

Thanks for this article. I learned so much about Gudy and the Colorado Trail!

Thanks for reading, Dana!

Thanks for reading, Dana!

Add new comment