We’ve seen the images of Rosie the Riveter, but what about Rosie the Juror? In summer 1945, as the Second World War drew to a close, women in Colorado made their own history by entering the jury box for the first time. This was part of a long and widely-publicized campaign that hinged on ideas of chivalry, citizenship, and strategy.

While we may find ourselves grumbling about the duty of jury duty today, this was in fact a major step in the movement toward equal rights for American women. Until women served on juries, they remained caught in a catch-22. Female defendants were denied the opportunity to be assessed by a jury that might experience the world as they did; Susan Glaspell’s short story “A Jury of Her Peers'' illustrates how this might play out in fiction.

Meanwhile, female would-be-jurors were denied a fundamental right of citizenship, as Burnita Shelton Matthew’s argued in “The Woman Juror,” published in Women Lawyers’ Journal in January 1927. Matthew ends on the note “Jury service is an important part of the administration of justice, and women lawyers everywhere should give their active support to movements in [sic] behalf of women jurors.” Colorado would remain free of women jurors for another two decades.

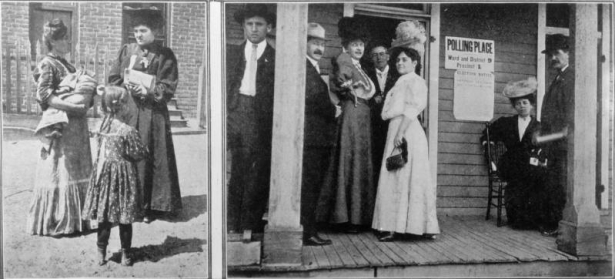

In many cases, jury duty was intimately tied to voting rights, which Colorado women won through a popular referendum in 1893. As an added benefit, women were formally eligible for jury service, though this rarely played out in reality. In a 1904 National Magazine article titled “Women in the Jury Box,” Ida Husted Harper wrote:

“In Colorado...the law for jurors has been construed by judges to apply the same to women as to men, but has been so adroitly managed that no women ever has been summoned.”

This was not specific to Colorado but rather was typical of the American West. Wyoming claims the title as the first location a woman ever actually served on a jury, with multiple women serving in 1870 and 1871. However, the precariousness of that right was on full display when a new judge took charge and reinterpreted the statute; Wyoming women became ineligible as jurors until 1949.

Similar occurrences happened in Washington and Idaho. Utah formally exempted female jurors from having to serve, but civic-minded women could choose to waive that exemption after 1898. In 1911, Washington finally broke the proverbial dam of allowing women voters to serve as jurors, shortly followed by other states where women were voting as well.

1913

But Colorado wasn’t part of this initial push. By 1913, the Colorado Federation of Women’s Clubs campaigned for a law specifically admitting female jurors. State senator Helen Ring Robinson also put forward a bill that would change the state constitution in three ways: allow three-fourths of a jury to return a verdict; admit female jurors, with the option of exemption should a woman not wish to serve; and allow for a thirteenth juror if any sitting juror fell ill during the course of a trial.

Robinson’s bill was killed in committee, failing by a single vote to move toward a constitutional amendment. The Rocky Mountain News noted that senators mysteriously “disappeared” during the vote, accusing them of ducking out to avoid voting.

Colorado Senator John Pearson highlighted the connection between the right to vote and the duty to serve on a jury, stating, “I was against woman’s suffrage...and I believe that it would not carry again in this state” (Rocky Mountain News, Feb. 1, 1913). When women’s jury service was put to a public referendum ballot vote in November 1914, it again was defeated by about 9,000 votes.

1936

By 1920, with the passage of the 19th Amendment to the U.S. Constitution granting woman suffrage, eleven states allowed for women on juries. With the right to vote, many states automatically added women to the pool of jurors as a matter of legislative language. Unfortunately, Colorado yet again did not fall into this category. When a 1936 amendment attempted once again to allow women to serve on juries, the Denver Post newspaper’s editorial team decried it on the usual grounds:

“It would be a serious mistake to take women from their homes, mothers from their children, and force them to do jury duty. The expense of providing duplicating accommodations for women jurors and men jurors would be a considerable additional financial burden upon counties least able to bear this.”

In their defense, this editorial opinion was in keeping with the Post’s admonition to “VOTE ‘AGAINST’ EVERYTHING YOU DO NOT UNDERSTAND OR CANNOT AFFORD.” Still, after two losses, the women’s judicial rights groups were still pushing for reform.

1944

On February 3, 1941, the Rocky Mountain News ran two articles illustrating that times were changing for women jurors in the state. The first, a “special correspondent” piece out of San Francisco (where women had been allowed on juries as early as 1918), included numerous quotes arguing for women’s fitness. In various judicial officers’ experience, women are “as qualified and competent as men,” “keen-minded, conscientious, and essentially fair,” and “show a great desire for justice, always are true to their oath of service and are not, as some persons seem to think, overly anxious to return indictments” (p. 3).

Later in that same issue, the News published an opinion piece bringing the issue closer to home. The Kramer-Pellet-Grimes resolution, then in the Colorado House for addition to the ballot, would refer a constitutional amendment to the people. Its passage would allow women on juries.

The question made it to the statewide ballot in 1944. Eudochia Bell Smith would write in They Ask Me Why that “it was one of the hardest fought bills ever passed by the Colorado Senate” (p.18).

But it was largely overshadowed by that year’s presidential contest between Franklin Roosevelt and Thomas Dewey, not to mention the continuing second World War. Compared to previous efforts to add women to juries, there was almost no mention of it in Colorado papers the week of the election. The Republican-leaning Denver Post didn’t even take a stand on the issue in their ballot recommendations. Perhaps the newspaper felt it was simply a done deal, as the legislature-referred constitutional amendment passed in a landslide. After decades of debate and struggle, Colorado women became eligible for jury duty.

Joining the Jury Box in 1945

In January 1945, Edna Ruske, Anna Bradley, and Carrie Royal made Colorado history as the first women jurors to hear a case; their service predated the traditional enabling act that would come out of a referred amendment. They formed the entire jury hearing a case involving the purchase of the Boulevard Hotel and the three women, all “housewives,” were praised as having “‘acted like gentlemen in every respect’" (Denver Post, 12 Jan 1945 p.24)

District Court jury service, including criminal trials and major civil trials, was opened to women in May of that year. Of the 6,800 Denver women invited to the jury pool, the vast majority (about 5,000) opted not to take the option of exemption from service. First drawn for the District Court jury pool was Sadie Brugger who, perhaps displaying some naivete amidst her excitement, told the Denver Post,

“I see no reason why women shouldn’t be just as good jurors as men. We’re governed by the same laws….What I’d like would be to sit on the jury in some of these divorce cases. It’s about time the women had a chance to get back at the men there.” (Denver Post, 27 May 1945 p1).

The next month, women were prolific on juries in courts, proving that, after decades of struggle and debate, change can finally happen swiftly and without much furor.

Once again echoing suffrage, though women were finally allowed on juries in Colorado, 1945 was not the end of the national fight. By the end of 1945, it was clear that the arc of history was bending toward progress, with more than half of all states allowing female jurors. Women in Mississippi (the last state to include women on juries), were ineligible as late as 1968. Even after that date, “opt-in” policies, exemptions, and peremptory challenges continued and continue to shape the make-up of juries and prevent the ideal “made up of one’s peers,” as promised in the Magna Carta (1215) and U.S. Constitution (ratified 1791).

A Note about Intersectionality and Women's Rights

It’s worth ending this article with a comment that applies to almost all writing about women’s rights: the information in this post mostly pertains to white women’s jury rights, as we were unable to find much on the history of women jurors of color (mostly Black women jurors) and even less on Black women jurors in Colorado. If you are interested in more general studies on jury service by Black women, the following may be of interest:

- Revising Constitutions: Race and Sex Discrimination in Jury Service, 1868-1979, a dissertation by Meredith Clark-Wiltz at the Ohio State University.

- “What's so Magic[al] About Black Women?" Peremptory Challenges at the Intersection of Race and Gender, by Jean Montoya, published in the Michigan Journal of Gender & Law

- RACE AND THE JURY: Illegal Discrimination in Jury Selection, by Equal Justice Initiative

Select Sources

- Western History Subject Index articles on "Women as Jurors"

- McCammon, Holly J. et al. “Becoming Full Citizens: The U.S. Women’s Jury Rights Campaigns, the Pace of Reform, and Strategic Adaptation.” American Journal of Sociology 113, no. 4 (2008): 1104–47.

- Marder, Nancy S., "The Changing Composition of the American Jury" (2013). 125th Anniversary Materials. 5.

Comments

Sarah,

Sarah,

A well written & enlightening (shocking) article. Thanks for that!

Thanks for reading, Peter! It

Thanks for reading, Peter! This history certainly caught me off guard.

Thoroughly researched and

Thoroughly researched and interestingly presented! I realize now that I had assumed that women began serving on juries at the same time they were granted suffrage. If I am ever in the position of being part of a trial, I am sure glad that I will be in front of a jury composed of all genders.

Same here, Megan! Thanks for

Same here, Megan! Thanks for reading and commenting.

Add new comment