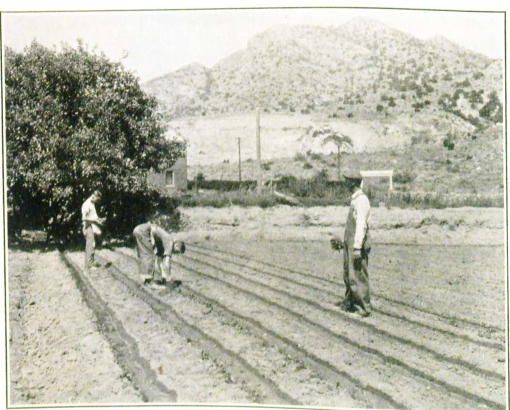

“On a fall day there is certainly no more picturesque sight in or near Denver than is to be found in this little known section of the city. Italian women, some quaint, some utterly charming, with their broad brimmed hats and bright colored work frocks, men with great sombreros – look though they were painted against the bright blue sky and the startlingly vivid green of the celery leaves…,” Municipal Facts, August-September-October, 1926.

This quote, which was paired with the photo on the top of this blog, describes a sight that was once a beloved harbinger of the holiday season in Denver: the harvesting of a massive celery crop.

Colorado, and more specifically the city of Denver as well as Jefferson, Arapahoe, and Adams counties, once produced bumper crops of a variety of celery called Pascal Celery, which was a nationally known staple of Thanksgiving and Christmas dinner tables.

But what made Pascal celery unique was the practice of burying the plants at harvest time to create a unique flavor that’s not found in store-bought celery today.

The practices of burying celery (known as “trenching”) and covering the stalks of the plants with newspaper (known as “blanching”) were especially popular among North Denver's large Italian immigrant community, though the techniques were used across the country.

But why would anyone harvest perfectly good celery only to immediately bury it in a trench full of dirt?

The Basics of Blanching and Trenching

Contemporary celery is crunchy and slightly bitter, but heirloom celery varieties were quite a bit more bitter and required an extra step to make them more palatable. That's where blanching (the practice of covering the bottom of celery plants with newspaper) and trenching (the practice of burying celery in organic matter) come into the picture.

Depriving the plants of light makes the stalks turn a bleached-out white, while adding a sweet flavor and a buttery texture. Anthony Spano of Spano's Produce says that trenching breaks down the stringy parts of the celery, which gives it its distinct texture and removes the bitter taste.

Trenching celery was, according to an October 17, 1938, Denver Post article, discovered by an Italian gardener named Pascal who covered some immature celery plants with dirt. Pascal discovered that burying the stalks of the plants while leaving the leaves exposed made the celery stalks taste sweeter. He started experimenting with the technique and took it public in 1889.

In Colorado, the Spano family (who still farm celery in Adams County to this day) are generally credited with being the first local farmers to harvest Pascal celery at their Adams County farm. Anthony Spano of Spano's Produce says that his family was likely one of the first, but that a large group of local Italian families all put the first celery in Denver ground around the same time.

Though blanched and trenched celery was both popular and profitable, it was incredibly labor-intensive to produce. Celery growing is, in fact, much more complicated than most people who aren't farmers might imagine.

Celery farming is a year-round process that starts with seeding on homemade hot beds in March or April. Once the seedlings sprout, they’re moved to the fields where they are individually inserted into the ground by a laborer who makes the hole for the plant with their fingers.

During the growing period, celery crops were notoriously delicate and could easily succumb to deadly fungi during Denver's brief wet season.

When harvest time arrived in the fall, farmers would designate a portion of their crop for blanching. This was the celery that would be sold at markets for Thanksgiving. Blanching involved wrapping the stalks of the plants in newspapers (one sheet of paper if the worker had a Denver Post and two for the tabloid-sized Rocky Mountain News).

The plants would remain covered for about four weeks, before being harvested and sent off to market.

Celery that was bound for the Christmas season was pulled from the ground and replanted in a 12-inch trench, leaving only the leaves exposed. Organic material such as manure was added to the trench to create natural heat, which helped decompose the celery, giving it its signature sweet taste.

(For an extremely detailed look at the entire celery growing process, check out Growing Pascal Celery in Arvada by Lawrence Lotito.)

Bushels of both trenched and blanched celery were a popular item every fall at Denver-area grocers in the 1930s and, according to Lotito, every year a bunch would be sent to the White House.

Why Does Celery Grow So Well in Denver?

So how did Denver become a celery world power?

The answer lies in the well-drained, gravelly bottomlands around the Platte River in Denver and Clear Creek in Jefferson County, as well as farmlands in other parts of the state. Since overwatering is a serious danger to celery crops, well-drained soil is a must.

It’s worth noting that areas of Adams County and the Platte Bottoms, where Italian truck farmers prospered, were once referred to as “the Poor Farm” because of their supposed value as farmland.

Celery had been planted in Colorado since the 1880s, but seemed to reach its peak in the years preceding World War II.

By 1934, Colorado Pascal Celery was being shipped to every state in the nation, and most of that product came from farms in Jefferson and Adams County.

That same year, a State Agricultural Bulletin titled Celery Production Colorado pointed out that Jefferson, Adams, and Pueblo counties each had 260 acres of celery fields. In 1933, the state produced about $6.5 million worth of celery in 2021 dollars.

But not all of Colorado's Pascal celery came from full-time, professional farming operations. Much of it came from very small plots that were tended by Italian families, who kept the celery for their own use or sold it at local markets such as the Denargo Market.

These are the same folks who created the "colorful scene in the Platte River bottoms in the fall of the year," which was described in Municipal Facts.

Whether the farm was big or small, celery was not a crop that could be handled by anyone short of an expert.

A Brighton celery farmer named F. F. Burton commented to Municipal Facts on the subject saying, “Celery is one of the more treacherous crops - in fact it may be the most treacherous crop. In order to grow celery you have to understand it. Let it get too chilly in the spring and it will go to seed. Give it too much water and it will rust.”

And that’s saying nothing of the incredible amount of manpower it took to bring a celery crop to harvest.

The Fall of Pascal Celery

The manpower required to bring in Pascal Celery also played a major role in the crop’s decline in prominence in the Denver area. By the time World War II rolled around, many of the men who once worked the celery fields were sent off to war, dealing a crushing blow to the business.

By the 1950s, demand for trenched and blanched celery had plummeted. A December 6, 1953, Denver Post article featured an interview with Adams County celery farmer Louis Pedota who explained that increased shipping costs, lower demand, and the rise of supermarket chains had seriously impacted his business.

Pedota said that in 1952 he’d sent 800 dozen bunches of celery to market, while in 1953 he only sent 100 dozen.

Though trenched and blanched celery is an obscure corner of the agricultural world, it has not been completely forgotten.

In Arvada, family farm operations such as Spano’s Produce harvest trenched celery every October for a small, but dedicated, group of local Italian Americans who crave the sweet, buttery taste of trenched Pascal celery on their holiday tables. But because our local climate is drier than it was in the 1930s, trenched celery is only available for Thanksgiving, as keeping it until Christmas is no longer viable.

Spano says he doesn't put as much celery in the trench as he once did because of reduced demand, but plans on keeping the tradition alive, "...as long as I'm around."

Comments

Excellent article Brian! I

Excellent article Brian! I have got to try this next year.

Just FYI my family farmed

Just FYI my family farmed just west of Spano's we raised celery long before they did. We were one of the largest growers of Pascal celery. Also made our own seed and also sold seed to Western Seed.

I still have the trench

I still have the trench cutter that we used when we raised celery in my yard. It usually took two tractors to pull the trench cutter as it cut out a swatch about ten inches wide and twelve inches deep. The cutter overall length is about six feet long. It was easier to pull it through sandy soil than heavy clay soil.

Brian--Great piece of

Brian--Great piece of research. I sent it to my aunt, June Spero, who wrote back a lengthy email, which I am going to share unedited with her permission---tantissimi auguri di un felicissimo anno nuovo!

"My grandmother Clara (Spano) Elliott aka Alioto, and my uncles Sonny and nanny were some of the "Spano" clan who started the "bleached" not blanched celery. They would trench the celery in the fall, and then when the celery was ready and the holiday prices were up, they would dig up the trenched celery, unwrap the newspaper. trim the root and prepare for sale to the brokers at Denargo market, or sell to the Green Brothers, who shipped throughout the US. Colorado "Pascal celery" was world , or at least US known. They covered the trench with straw, then manure, and then dirt, not straight manure on the trench. Often it was freezing when they trimmed the celery for market. They would have a half barrel in the field with a fire going, so they could warm their hands while working.

When the orders were done for the day, my uncles and their first cousins (who lived on adjacent farms) -- my grandmother's nephews, would all gather at my grandmother's house. They would enjoy her cimino (sesame) biscotti, coffee, and the celery would be washed and dipped in a bowl of olive oil and salt and pepper to eat with the cookies and coffee. This scene was repeated often from a week or two before Thanksgiving until after Christmas. I lived with my parents and grandparents so I was a witness to this rite. The one thing I remember is that my mother and grandmother were also out there in the cold trimming the celery along with the men!

My uncle won prizes at the state fair with bunches (12 stalks) that stood well over 3 feet high and weighed well over 150 lbs. It took 2 men to lift it onto a crate. We had film of it, but alas a fire at my brother's house burnt the film! You might be able to find the article in the Denver Post. I think early 50's, maybe '53. It was labor intensive, but for years people knew of pascal celery from CO and were willing to pay the price. What really also contributed to the death of the industry was contaminated seed from CA. My uncle would start the plants in the greenhouse and the transplant into the fields. He got bad seed that created root rot in the plants. The disease got into the soil and it was way too expensive to eradicate the disease, so the celery growing came to a halt!

Pascal celery was a large part of my formative years!

The articles are a great

The articles are a great testament of the hard work our families and relatives put into providing this wonderful celery.

My grandfather Sam Spano, was one of the brothers of Clara (Spano) Elliott. Needless to say, most of the farming brothers, sons and cousins of Clara and Sam took great pride in perpetuating the tradition of this cherished celery process, laborious as it is. They all set the cornerstone of building this strain of seed which would be rare to find today.

Most people could only imagine how wonderful it was. I too, like June Spero, remember as a child the magnificent smell of the celery and dipping into a dish of olive oil, salt and pepper. We continue to eat the celery hearts today that same way, even though it's not quite as special.

Thanks to Anthony Spano, and probably a rare few other small farmers, attempt to grow and nurture Pascal celery of recent years.

Thank you for this

Thank you for this information

Thank you to those who have shared their memories of this time.

Our family worked for the Denver Post during those years.

Our family stories included supplying the newspapers to the farmers who then used them to line the trenches for Pascal celery.

And in the Wheat Ridge area,

And in the Wheat Ridge area, there was H.B. Martensen, one of the early pioneers of that town. H.B. and his wife Lena immigrated from Denmark. After H.B. worked in other cities across the Eastern part of America, he settled around Lakewood and started a dairy business. Then he moved to Wheat Ridge where, in 1905, he established a successful celery "empire" which was taken over by his two sons Louis W., and Edward Martensen. The two sons developed celery noted for its tenderness and flavor, and which was sent to many parts of America. I believe that L.W. Martensen School in Wheat Ridge was named after one of the sons, Louis W. My thanks to the Wheat Ridge Historical Committee.

Wheat Ridge has a pretty

Wheat Ridge has a pretty amazing agricultural history. Thanks for sharing!

I've only been in Colorado

I've only been in Colorado since 1978, am a horticultural fiend and am a serious student of local history. It is SO cool to read of all of these recollections - all resulting from the wonderful newsletters from the DWH&G at the Denver Public Library. Hooray to all and congratulations for a mission well executed-

Wonderful information! My

Wonderful information! My hubby, a true Denver native, knew all about the Italian community and celery growing. Fun to be reminded of it all.

Add new comment