Portia Lubchenco was one of the first female chiefs of staff of any hospital in Colorado. "Doctor Portia" survived the Russian Revolution and helped modernize hospitals and medicine throughout Colorado.

Portia Mary McKnight was born August 6, 1887, outside of Charleston, South Carolina. Her father Peter ran a successful cotton plantation, while her mother Lula looked after Portia and her eight siblings. From an early age, Portia was known for her intelligence. After Portia finished high school, she told her family she wanted to study to become a doctor. Her mother and father told her medicine was no job for a woman.

Portia decided to study business and education at South Carolina Co-Educational College. She was an excellent student, and received an offer to become a teacher soon after graduation. Portia accepted, though she did not forget her dream of becoming a doctor someday.

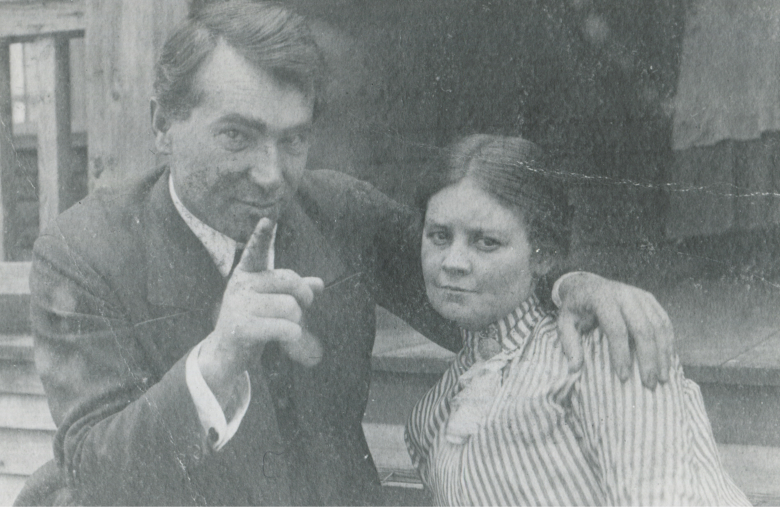

In 1907, Portia met Alexis Lubchenco, a Kyïv-born agronomist who came to South Carolina to study American plantations. Alexis stayed on the McKnight plantation while learning how Portia’s father ran his cotton business.

Portia and Alexis became friends. Portia shared her dream of becoming a doctor someday, but told Alexis her family would never approve. Her parents always thought Portia’s main goal should be to find a rich husband.

Alexis told Portia that in Russia, it was not unusual for women to become doctors. In fact, his own sister was a doctor in Russia. Alexis encouraged Portia to follow her dream and apply to medical school.

Portia first applied to the South Carolina Medical College. The director of the school informed Portia that they were not willing to accept a female medical student.

Portia did not want to give up. She approached the medical school at North Carolina State University with her application. They agreed to accept Portia as a student. She became the first woman to enroll at the medical school at North Carolina State.

After he finished his studies in South Carolina, Alexis returned to Russia to accept a job as Professor of Science at the University of Moscow. He and Portia kept in touch with frequent letters throughout her four years of medical school.

In 1912, Portia shared the news that she was going to be the first woman to graduate from the North Carolina State Medical College, and her excellent grades meant she would graduate second in her class. Alexis promised to return to the United States for her medical school graduation, and told her he had purchased a ticket on the new steamship Titanic.

On April 15, 1912, just days before her graduation, Portia read in the news that the Titanic hit an iceberg and sank, killing almost everyone on board. Portia checked the news daily with the lists of deaths, looking for her friend Alexis’s name.

Imagine Portia’s shock when on the day of her graduation, she looked into the audience as she received her diploma and saw Alexis Lubchenco sitting with her family. Alexis told Portia that he had been delayed, and just barely missed boarding the Titanic. He had to take another steamship the next day, avoiding the disaster.

Portia and Alexis saw this as a sign. Although Portia had been accepted to a competitive internship at the Massachusetts General Hospital, she turned the offer down. Instead, she and Alexis married shortly after her graduation, and she returned with him to Russia.

Portia, who had never traveled beyond the southern United States, adapted quickly to Russian life. She learned the language and customs, and soon Dr. Portia Lubchenco became a well-known specialist in delivering babies. Portia and Alexis had three children in Russia. They spent most of the year in Moscow, and lived in Turkmenistan during the summer, where Alexis owned a large cotton plantation.

But Portia’s happy days in Russia were numbered. Almost every member of Alexis’s family was a “white revolutionary.” This meant they wanted to overthrow the existing Russian government, and replace it with a modern republic. Alexis was caught at a secret meeting of white revolutionaries and thrown in prison for three months.

The white revolutionaries managed to overthrow the imperial Russian government, and replaced the Czar with an elected president. The republic did not last long. A more radical group of revolutionaries, called “red revolutionaries” or Bolsheviks, defeated the white revolutionaries and began communist rule under Vladimir Lenin in 1917.

This was a very dangerous time to be in Moscow. Not only was there civil war between the Bolsheviks and the white revolutionaries, but World War I meant the Germans had invaded Russia, and there was heavy fighting in Moscow.

Portia was terrified that her husband, a close friend of the defeated Russian president, would be executed by the Bolsheviks. She tried to convince the American passport ambassador to issue immediate passports to herself and her family to return to the United States. He promised her there was nothing to worry about and that she did not need passports issued as quickly as she wanted.

When Portia returned to ask him if he could change his mind, she found that he was shot to death, and the American passport office was destroyed. That same night, the Lubchencos were awakened by Bolshevik “inspectors” who ransacked their home. This was the last straw.

Portia and Alexis hurriedly gathered their children and a few belongings, and fled east through Siberia into China. Portia knew if they tried to escape through Europe, they would be found by the Bolsheviks and killed.

Since the Lubchencos were able to bring very little with them, they soon ran out of money. Portia traded her medical skills in exchange for train tickets throughout Siberia and China. From China, they managed to get a ship to the United States. The Lubchencos returned to South Carolina, where Portia’s family helped Alexis begin a new cotton plantation.

The plantation was a success, and Portia soon had a booming medical business as well. She rode a horse and buggy throughout South Carolina to deliver babies and tend to the sick. She was a well-respected and beloved doctor. In South Carolina, Portia had two more children. She and Alexis had a very happy marriage.

Portia knew it was important to keep up with advancements in medicine. She enrolled in extra medical classes at Duke University, the University of South Carolina, Johns Hopkins University, the University of Virginia, and the University of Chicago so she could become an expert in new treatments. Portia was well known for her skills using modern medicine.

In 1931, a boll weevil invasion destroyed most of the crops in South Carolina, including Alexis’s cotton plantation. The widespread poverty of the Great Depression and the crop failures meant Portia’s patients could not pay their medical bills. Portia and Alexis worried their family would become bankrupt.

Portia’s brother, Jim, had moved to Colorado and set up a successful medical practice in the town of Haxtun. Jim invited his sister to join him as his partner. Portia accepted, and the Lubchencos made the journey to Colorado. Alexis was unable to keep farming cotton in the dry Colorado climate, so he accepted a job as laboratory technician in Portia and Jim’s medical office.

“Doctor Portia” as she was called, became incredibly successful in Colorado. She opened her own office in Sterling in 1936, and traveled throughout Northeast Colorado to deliver babies and heal patients. Portia helped renovate and modernize the Good Samaritan Hospital in Sterling, and became the hospital’s first Chief of Staff. She was known for her sharp sense of humor, keen intelligence, and true care for her patients. Portia and Alexis’s five children grew up to become prominent members of the Colorado community. Two sons and a daughter followed in their mother's footsteps and became doctors. One son became an engineer, while one daughter became a teacher.

Alexis died in 1941. Fifty-four year old Portia was heartbroken and never remarried, although she lived until ninety one. After Alexis’s death, Portia threw herself into her work even more than before.

In 1954, Portia was named Colorado Mother of the Year, not only for raising five exceptional children, but for her extensive medical work with mothers and children. Although Portia received many medical awards during her career, she always thought her “Mother of the Year” award was one of her best achievements. Portia also won the prestigious Colorado Medical Society award in 1962. Portia was honored for her work to help more mothers and children survive childbirth, which could be very dangerous. Portia also became the very first woman to become a member of the South Carolina Hall of Science and Technology.

In 1964, after years of being asked to share her story, Portia published Doctor Portia. This autobiography was written with the help of journalist Anna Petteys, and told the story of Portia’s exciting life in Russia and medical work in the United States. Doctor Portia became a very popular book.

Portia formally retired in 1966. She decided to move to Denver to be closer to her children and twenty-one grandchildren. But retirement did not suit Portia. Even though she was elderly herself, she set up a small medical office in her Denver home, and opened a medical practice for older patients at a reduced rate. Eventually this became too much for Portia, and she retired a second time at the age of eighty-five. Portia died peacefully at the age of ninety-one in her Denver home.

Dr. Portia Lubchenco became one of Colorado’s most prominent doctors in a time when there were very few female doctors anywhere in the United States. She helped bring many modern medical practices to Colorado. “Doctor Portia” improved medical care for pregnant women, women going through childbirth, babies and the elderly. She was known for her intelligence and her deep concern for all her patients. Today, Portia Lubchenco is remembered for her work to modernize and improve Colorado hospitals.

agronomist - a scientist who studies crops, soil and farming

internship - a job given to a student or trainee to learn how to master a certain profession

Czar - the Emperor of Russia

Bolshevik - the Russian Communist Party

ransack - to tear apart a home, steal things and cause damage

boll weevil - a small beetle that eats the cotton plant

Great Depression - a long and severe economic downturn that lasted from 1929 through most of the 1930s after the collapse of the stock market

prestigious - something of high status that commands respect and admiration

autobiography - an account of a person's life written by that person

How do you think Portia Lubchenco's life would have been different if she stayed in Russia?

Portia thought it was important for people in rural areas like South Carolina and Northern Colorado to have access to hospitals and good doctors.

- Do you agree with Portia? Why or why not?

Portia was determined to get her medical degree even after being told that she could not do so. Think of a time when you wanted to do something but were told you could not do it. Were you able to do it anyway? What was that experience like?

Portia Lubchenco Manuscript Collection (primary sources including letters, degrees, photographs and other information about Portia and her family. Includes drafts of the book Doctor Portia. The Portia Lubchenco Manuscript Collection can be viewed in person on the 5th floor of the Denver Central Library.)

Biography Clipping Files (newspaper and journal articles about Portia Lubchenco that can be viewed in person on the 5th floor of the Denver Central Library).

Portia Lubchenco in the Denver Public Library Digital Collections

Manuscript Monday: Dr. Portia Lubchenco

Doctor Portia: Her First Fifty Years in Medicine (Portia Lubchenco's autobiography, co-written with Anna Petteys, which can be viewed in person on the 5th floor of the Denver Central Library)