Pauline Robinson was the first African American librarian in Denver and fought for equal rights and better educational opportunities for children. This is a special biography brought to us from the staff of the Pauline Robinson Branch Library.

Pauline Short Robinson was born in Gay, Oklahoma, the middle child of eight siblings. Her father provided the family with over 100 books at their home and made homework a top priority. But it was Pauline’s grandfather who taught her how to read, even before she attended grade school. Pauline graduated from Douglass High School, located in Lawton, Oklahoma in 1933.

When Pauline came to Denver, she attended the Emily Griffith School graduating in 1935. She married in 1940 and changed her name to Pauline Short Robinson. Pauline earned a bachelor’s degree from the University of Denver and, after even more studies, she graduated in June 1942 with her education being funded by a full scholarship from Delta Sigma Theta, Inc. Ms. Short entered the University of Denver School of Librarianship. With a lot of hard work, she graduated as the first African American librarian in Denver in June 1943, with a Bachelor of Science in Library Science.

Pauline’s civil rights accomplishments began when she was a student at the University of Denver in 1942, where she created opportunities for black teachers to teach at any grade level in the Denver Public Schools. At that time black teachers were only allowed to teach kindergarten and first grade due to the segregation that was still in practice. Pauline was also instrumental in desegregating Lakeside Amusement Park through a lawsuit.

Mrs. Robinson’s library career began with her employment at the Community Vocational Center Library located in the Five Points neighborhood that she lived in. Five Points was a mostly black neighborhood. The community often didn’t receive the same city resources as other neighborhoods. This library wasn't part of the Denver Public Library (DPL) system and only received items that DPL was getting rid of. Regardless of the poor funding this library received, Robinson was able to create a welcoming environment that provided both relief and resources in education to the growing group of children in the community. Because the funding was so low, Robinson had to use her own money to buy books for the library and, at times, even put on bake sales to raise money to buy them.

Pauline left Denver and her job for a few years, but, when she returned to the Community Vocational Center Library, she found it in dire straits. Pauline had been supporting the African American community through her work at the library, but when she left, there was no one to fill her very active role. This meant less people were going to the library and funding dropped even more. DPL was going to shut down the branch, so Robinson and a few school principals lobbied for a new branch in the neighborhood. It was called the Cosmopolitan Branch Library, and Pauline Robinson was named the first African American librarian in 1945.

As a community leader, Pauline organized the first Negro History Week at New Hope Baptist Church, which later became Denver’s Black History Month. The first Negro History Week Celebration was held in 1947 at the Cosmopolitan Branch to a standing-room-only crowd. This event went on to become the Annual Negro History Program, held from 1948 until 1953. As chairwoman of the program, Pauline got the volunteers together, did all of the research, and wrote the historical script for a music series dramatizing the fight for civil rights. With choirs from various churches in the area participating, the first program was held on Thursday evening at New Hope Baptist Church and repeated on Friday evening at the University of Denver Chapel.

Another great accomplishment by Pauline was starting a Negro History Collection for Denver Public Library. She convinced local businesses to sponsor a bake sale at which more than 150 pies were sold, raising more than $40.00. This money was used to buy books directly, so that between 15 to 20 books could be brought in to start this special collection. Mrs. Robinson also asked local businesses to fund African American magazine subscriptions and local community members paid for various African American publications. Because these materials were introduced to DPL, it provided the opportunity for adults to use the library for all these new materials.

Pauline started the Reading Is Fundamental to Denver program, and for many years was the Chairwoman of the Vacation Reading and National Children’s Book Week celebration in Denver, which later became the DPL Summer of Adventure program. She knew that reading was so very important to the health and well-being of every child. And with so many children without books at home, this program provided books and goals to help them keep reading during the summer months. This program became one of the largest in the country. Over 30,000 children joined the program and some read as many as 75 books in just three months.

Pauline was named Coordinator of Children’s Services in 1964 and helped to build the current collection of children's books at DPL. Throughout her career, Robinson focused on finding people who lacked books and a supportive environment — the resources they needed to succeed. Pauline Robinson was the first to develop what were called Heritage Book Lists on minorities. The Children’s Services department prepared book lists on Mexican Heritage, African American Heritage, and Native American Heritage. This program helped to grow the amount of diversity in Denver Public Library’s book collection.

When Pauline moved to the Warren Branch Library in 1954, she took on the Vacation Reading Program. This program was designed to help foster educational growth in children.“From time to time a child came in with a parent to the library during school hours for me to monitor their reading improvement. Grade level was determined by listening to the child read aloud. Read Aloud books were then recommended to parents. Read aloud sessions were not to exceed 20 to 30 minutes at various intervals during the day. This repetition should not take place more than three or four times each day. I Can Read Books were recommended for the child to read aloud to his or her parent. On each occasion, the child’s reading improved until the proper reading level was reached.”

The Unlimited Education Opportunities program became today’s DPL Read Aloud Program, in which DPL librarians and other staff visit schools and read to children in classrooms. Mrs. Robinson had such an impact that the circulation of the Warren Branch went up by 20,000 books. Because of this and Pauline’s efforts to reach out to the community, the DPL received the Neil S. Scott Award on April 17, 1970.

Pauline was also one of the first librarians to make an effort to include teens and young adults in library programming. She held programs for them to hang out, showed them new books and information, and supported them in going to college and vocational schools. To assist in raising funds for the library Mrs. Robinson made a videotape for the 1990 Denver Public Library Bond Drive. Mr. Miller, President of the Library Commission, and Librarian Pauline Robinson went on Channel 6 in a library-sponsored series on South Africa.. Many TV appearances were made to promote Vacation Reading, National Children’s Book Week, and Children’s Services. Pauline also promoted the Read Aloud Program to pre-school children by going on the “Blinky the Clown” television program regularly.

Pauline served on the Denver Public Schools Council. This allowed her to bring together Denver Public Schools and Denver Public Library so they could work together on programs like the Summer of Adventure. Most of those programs still exist to this day. She was also on the selection committees for the nation’s two most important children’s book awards.

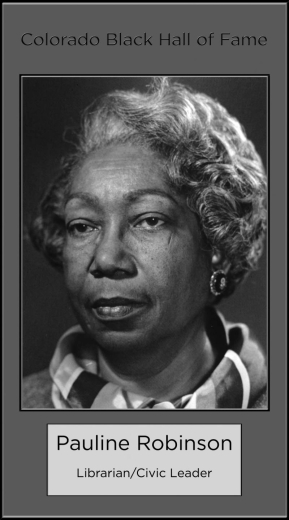

Pauline Robinson, Denver Public Library’s first African American librarian, was honored with entry into the Colorado Black Hall of Fame in 1973. She retired in early May 1979, after a serious car accident. DPL was looking to create another branch in the city and selected a site in northeast Park Hill. With much support from the community, DPL named the branch Pauline Robinson in Pauline’s honor. She was able to attend the groundbreaking in September 1995. The branch opened on March 29, 1996.

“‘It’s awesome… It’s overwhelming,’ repeated Pauline, who is rarely at a loss for words.‘The Collection is so much more extensive than I expected. But the best part,’ she added, ‘is that this has been given to me while I still can smell the flowers.’”

Pauline passed away on February 18, 1997; one year after the branch was opened. After her passing, in 2000, she was honored with her selection into the Colorado Women’s Hall of Fame.

segregation - racist rules that limit what People of Color (POC) could do in society and kept them separate from white people and opportunities

desegregation - giving people of color the access to the same resources that white people had

dire straits - a bad or difficult situation

lobbied - seeking change on an issue or policy

Why do you think Pauline thought she would be able to become a librarian in Denver when no other African American had done it?

Have you or someone in your family member ever done something that seemed impossible?

Are there ways in which you would like to serve people in your community like Pauline did?