Emily Griffith founded the Opportunity School in Denver, a unique school which offers job training and education "For All Those Who Wish To Learn".

Emily Griffith was born on February 10th, 1868 in Cincinnati, Ohio. Her father was a lawyer and her mother stayed home to raise Emily and her siblings.

The Griffiths were always very poor. Her father did not earn very much money because he would not take a case unless he thought the client was innocent. Eventually, Emily’s father quit his job to become a Presbyterian missionary. This made the Griffiths poorer than ever before.

Emily had to leave school after the eighth grade to help take care of her family. Emily’s parents and sister Ethel were often sick, and her sister Florence had a mental illness. This meant Emily had to do most of the work around the house. However, Emily kept a lifelong love of learning.

Her uncle ran a night school for adults, and inspired Emily to become a teacher herself. The motto of her uncle’s school was “For all those who wish to learn.” This saying stayed with Emily throughout her life.

When Emily was sixteen years old, the economy crashed and many people had to leave Cincinnati to find work. The Griffiths moved to Nebraska, hoping to make a living as farmers. However, they were not successful.

Her father and mother were too weak to work on a farm. Emily’s sister Florence developed epilepsy and needed many expensive doctor’s visits. As a result, sixteen-year-old Emily and her eighteen-year-old brother Charles were required to support their family.

Charles found a job at the post office, while Emily decided to pursue her dream of becoming a teacher.

The school board did not want to hire Emily at first because she was only sixteen and looked even younger. They worried she would not be able to control a one-room schoolhouse with students of all ages. They gave her a series of difficult tests before she could be allowed to teach. Emily passed them all easily.

Emily was put in charge of students between six and twenty-six years old. To save money, Emily spent time living with the families of her students. She would live with one family for a few weeks, then move on to another family.

Emily realized that most of the parents of her students could not read, write, or do basic math. Many people in Nebraska lived in poverty because the parents did not have the education to get high-paying jobs.

Many parents had dropped out of school when they were children to help with their family farms. Emily understood how hard this was because she also had to leave school early to support her family. Emily tutored the parents of her students when she stayed with them.

Since she only had an eighth grade education, Emily had to spend her nights studying to keep up with her older and more advanced students. She was able to teach herself many subjects.

In 1894, an unusually hard winter destroyed the few crops the Griffiths were able to grow. They knew they had to leave Nebraska or starve.

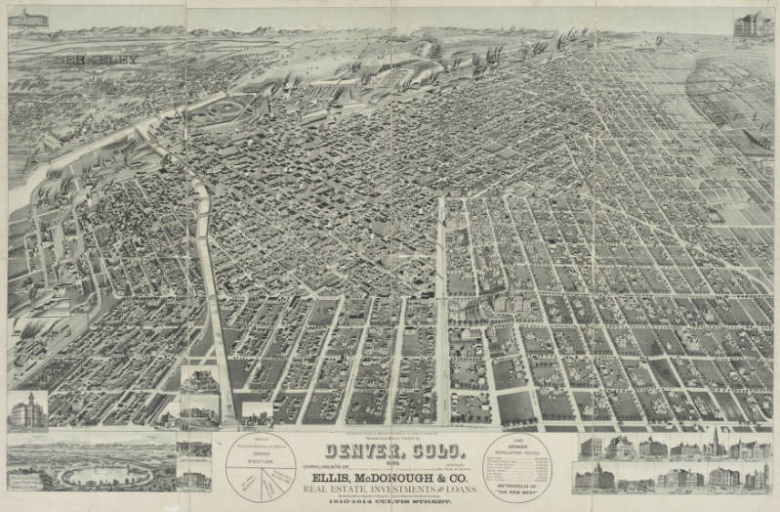

Emily convinced the Griffiths to move to Denver. She thought there would be many more opportunities for her family to make a living in Denver than on the plains.

Emily applied for a job as a teacher with the Denver Public Schools. On her application, Emily lied about her age and said she was fifteen years old. She was actually twenty-seven.

Emily did this because she did not want to be passed over for a job because she was an “old maid.” Although Emily had been proposed to several times, she always turned her suitors down. She did not want a husband to distract from her family or her work.

However, in the Victorian Era people believed the only reason someone would be unmarried was because something wrong with them. Emily did not want to be judged for not getting married, so she pretended to be a teenager. She always looked much younger than her age, so she was able to keep to this story for the rest of her life.

Emily had eleven years of experience teaching, but she could not use that to get a better job without revealing that she was not as young as she claimed. She had to work her way up from the bottom of the school system the way any new teacher would.

Emily started as a substitute teacher in elementary schools before earning a promotion to eighth grade teacher at the Twenty Fourth Street School in Denver's Five Points neighborhood.

Five Points was home to Denver's Hispanic, Jewish, Asian and African-American populations. Many new immigrants from around the world settled in the neighborhood as well.

Racist policies kept many Five Points residents from being able to earn good jobs or get a decent education. Emily saw that many of her students lived in extreme poverty.

Emily dedicated her spare time to giving free lessons to her students' parents and siblings. She helped immigrants learn English. She knew that the best way for people in Five Points to earn a better life for themselves was through education.

Emily's work did not go unnoticed by her community. In 1904, she became the Deputy State Superintendent of Schools. Many of her former students came to visit her office at the State Capitol when they needed help.

In 1909, Emily decided she missed teaching and returned to the classroom. However, the next year she was offered a position as Deputy State Superintendent of Instruction. The job would give her the ability to change the way students were taught throughout Colorado - a chance Emily could not resist.

However, Emily returned to her job at the Twenty-Fourth Street School in 1913 when she learned the school was failing under its new teachers.

She began teaching formal classes for adults at night. Her classes were practical - sewing, cooking, and English classes for immigrants. They were also extremely popular. Emily decided it was time to make her dream of a full-time school for adults a reality.

Emily met many important people while working for the state school board. She used those connections to build support for her new idea. She approached wealthy women for help, telling them it was a chance to do something good for those less fortunate. She convinced their businessman husbands that a school for adults would train skilled and productive workers.

However, some people questioned Emily's ability to run a school successfully. Even though Emily had practical experience as a teacher and school administrator, they claimed someone who had never even been to high school had no qualifications to start a school of her own.

By 1916, Emily managed to convince the school board that her idea would work. She was given an old, condemned school building. She and her supporters helped make the school safe for students to enter. Her school opened on September 9, 1916.

Emily took the motto of her uncle's school for her new school. A sign hung over the entrance to the school stating: "For All Those Who Wish to Learn." Emily named her new school the Opportunity School, because it would create opportunities for people who never had them before.

Everyone, including Emily, was shocked at how popular the Opportunity School was. Emily estimated the school would have two hundred students in its first year. Imagine her surprise when fourteen hundred students enrolled the first week!

Emily took her school's motto to heart. She did everything she could to make her school accessible to working adults. The Opportunity School was open thirteen hours a day, so students could come to class around their work schedules.

Her classes had no attendance requirements, as she knew her busy students might not always be able to make it to school. Students could learn on their own schedule, and complete classes in as much or as little time as they needed.

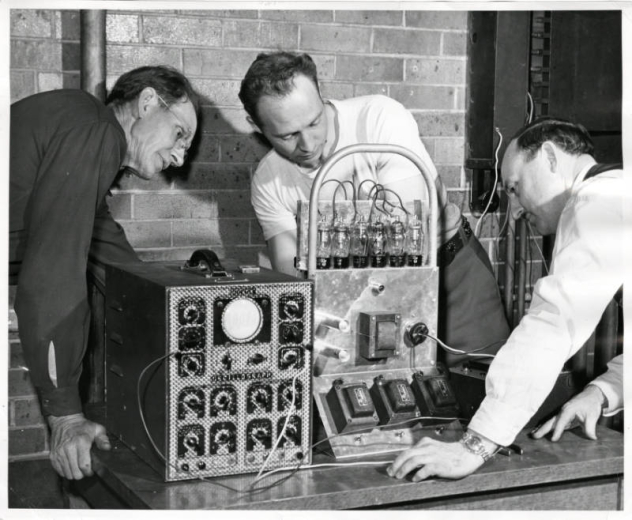

Everything taught at the Opportunity School was practical. There were classes in masonry (construction with stone), electricity, dressmaking, and millinery (hat making). Emily was often seen wearing the hats and dresses her students made. Emily worked with local employers like businesses and worker's unions to train students for the jobs that were needed. Classes were taught by working experts in each field.

There was no cost for classes at the Opportunity School. It was supported through the Denver Public School system and by donations from Emily's many friends. Whether people were looking to start a new, better job or earn a promotion by learning new skills, Emily made it possible through her new school.

Emily went out of her way to make sure all her students' needs were met. If a class was requested by more than twenty students, she would find someone to teach it. She sent teachers to hospitals to help students who were ill. After one of her students fainted from hunger during class, she began bringing a large cauldron of soup with her to the school. She would carry the soup on a streetcar with her. She usually fed around two hundred students a day.

By the time Emily retired in 1933, the Opportunity School had seen over one million graduates. In 1934, the school was renamed the Emily Griffith Opportunity School in her honor.

Emily retired to the town of Pinecliffe near Nederland, Colorado in a cabin she shared with her sister Florence. Emily did not want Florence to live alone because of her epilepsy. Emily's cabin was built by her close friend Fred Lundy, a retired teacher from the Opportunity School.

Emily enjoyed a quiet retirement. She and Florence would go hiking by day and have friends over at night.

This all came to an end in 1947. Emily's sister Ethel came to visit the cabin one evening, but there was no answer at the door. Ethel did not think anything of it and assumed her sisters were on a walk in the beautiful forest. When she didn't hear anything from Emily and Florence the next morning, she became worried. Ethel and her husband broke into the house and found that both Emily and Florence had been murdered.

Although both sisters had been shot, there was no sign of a struggle. In fact, the sisters had prepared dinner for three people, which meant they were expecting a guest. The police suspected a friend of Emily Griffith was her killer.

The world was horrified to learn of Emily Griffith's death. People could not believe that such a peaceful life had such a violent end. Police searched for months but never arrested anyone for the crime.

The police suspected Fred Lundy, who committed suicide after the murder, but this was never proven. Others thought Emily's sister Ethel and her husband arranged the murder, as they inherited Emily's large life insurance payment after her death. However, the murders of Emily and Florence Griffith are unsolved to this day.

During the 1976 celebration of Colorado's 100th anniversary, a stained glass portrait of Emily Griffith was hung in the State Capitol in Denver. It can still be seen today. In 1985, Emily became a member of the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame. In 2000, Emily was honored with a Millennium Award, given to the people who have had the largest impact on Denver since its founding.

The Emily Griffith School still trains adults today, though it was renamed Emily Griffith Technical College. Cuts to school funding meant that the Emily Griffith Technical College has charged tuition since 1991, but it is still a low-cost option for important job training. The Emily Griffith High School was founded in 1985 to give those who dropped out of high school as teenagers the chance to earn a diploma as adults.

Graduates of the Opportunity School have had a positive impact on Colorado and the world for over one hundred years!

missionary - a person who promotes a religion, especially Christianity

inspired - to make someone want to do something important or creative

motto - a short phrase used to explain the ideals of a person or organization

epilepsy - a disorder that leads to frequent seizures without warning

condemned - a building proclaimed to be unfit for use

accessible - easily used by anyone

Do you know any graduates of the Emily Griffith school? What was their experience like?

Emily Griffith had a policy that she would teach a class on any subject requested by twenty or more students. Imagine your school had this policy. What classes would you request?

How would Colorado be different today if Emily Griffith never founded the Opportunity School?

The Emily Griffith Opportunity School Records (The attendance and teacher records, plans, scrapbooks, manuals, and awards from the Emily Griffith Opportunity School through 1998. These primary sources can be viewed in person on the 5th floor of the Denver Central Library.)

Biography Clipping Files (Newspaper and magazine articles, including obituaries, about Emily Griffith that can be seen in person on the 5th floor of the Denver Central Library)

Books about Emily Griffith at the Denver Public Library:

- Emily Griffith: Opportunity's Teacher (a biography for young readers available for check out)

- Emily Griffith: Opportunity for All (part of the "Great Lives in Colorado History" series for young readers. In English and Spanish.)

- Bold Women in Colorado History (a book for younger readers that contains sections on several notable Colorado women, including Emily Griffith)

- Touching Tomorrow: The Emily Griffith Story (biography available to check out, or it may be viewed in person on the 5th floor of the Denver Central Library)

- "You Can Do It": Denver's Emily Griffith Opportunity School (a short book about the Opportunity School that may be viewed in person on the 5th floor of the Denver Central Library)

Biography of Emily Griffith from History Colorado

Emily Griffith in the Colorado Virtual Library

Emily Griffith in the Colorado Women's Hall of Fame

"Miss Opportunity: The Life and Times of Emily Griffith" (video about Emily Griffith from Rocky Mountain PBS)

1947 article on the murder of Emily Griffith from Time Magazine