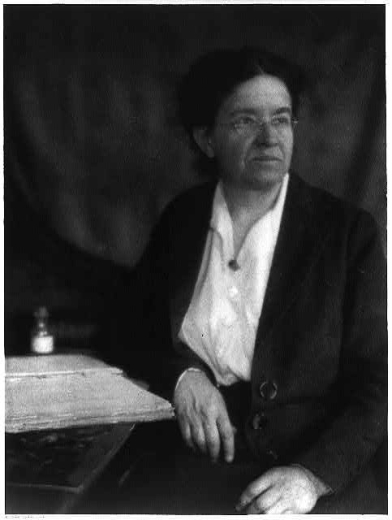

Dr. Florence Sabin was a medical research scientist who pioneered the field for women and helped improve the health of Coloradans.

Florence Rena Sabin was born on November 9, 1871, in Central City to George and Serena Sabin. George worked as a mine manager, and the family was comfortable. Her sister Mary was two years older than Florence, and the two were very close. The family moved to Denver in 1875, but tragedy struck when their mother Serena died after giving birth in 1878. It was Florence’s seventh birthday.

George Sabin did not feel that he could give his daughters a good home without their mother and needed to move back to the mountains. First, he sent them to live and study at Wolfe Hall, a boarding school close by in Denver. Then they went to live with their Uncle Albert in Chicago. While with Albert, Florence developed a love of music and for a while even thought of one day being a professional piano player.

Florence and Mary then moved to Vermont, where their father’s parents lived and where they could attend the prestigious Vermont Academy. After she graduated in 1889, Florence followed her sister to Smith College, a school for women in Massachusetts. She was a very good student in many things, but instead of focusing on music as she had planned, she decided to focus on science.

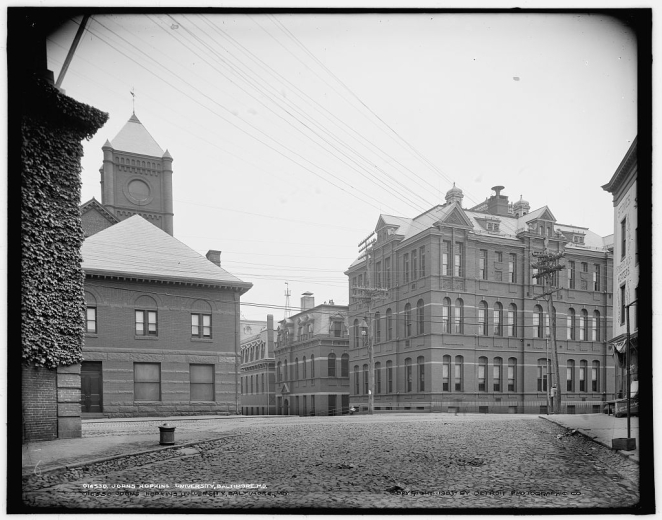

Florence thought she might want to be a doctor and so she spoke to the university physician, Dr. Grace Preston. Preston said two things that would come to be very important: she told Florence that the new Johns Hopkins Medical School would admit women and she told her that “any woman who wants to be a doctor must work for women as women, and not alone for herself.” A lot of people at that time didn’t think women were smart enough to be doctors, and so by defying expectations and becoming one of the few women doctors, Florence would become part of the women’s movement.

Florence decided that she would work to become a doctor and would go to Johns Hopkins to do so. However, she didn’t have enough money at first, so after graduation, she taught for three years to save enough for tuition. She applied to Johns Hopkins and was admitted in 1897.

In medical school, Florence learned about the parts of the body and used a microscope to research its smallest aspects. Students at Johns Hopkins were expected to do their own research and make their own discoveries. These were both things that Florence did very well and which she would continue to practice in her later life. She worked under a famous researcher, Dr. Franklin Paine Mall, studying the brain and the nervous system. Florence discovered that she could practice medicine and help people without the challenges involved in seeing patients. This was what she wanted to do.

Florence graduated in 1900 and continued working as a researcher with Dr. Mall. In 1903, she was hired as an assistant professor. She continued to research the body on the microscopic level, including watching the development of blood vessels in a chicken embryo. She later described this experience as the most exciting of her life.

Though well-liked by students and faculty, Florence was still treated poorly because she was a woman. When the school hired a new head of the anatomy department, she was overlooked and the job instead went to a man who had been her student. Despite this, she eventually became chair of the Histology department and was Johns Hopkins’ first female full (senior-level) professor.

Florence received a lot of praise throughout her life for being a “woman scientist,” but she hated being called that. She thought her work should speak for itself - woman or man - and so she worked as hard as she could to be a great scientist. In this pursuit, she also kept her word to “work for women as women” by breaking barriers to become the first female president of the American Association of Anatomists in 1924 and the first woman elected to the National Academy of Sciences in 1925.

In 1925, Florence was also invited to join the staff of the Rockefeller Institute for Medical Research as head of the Department of Cellular Studies. Though she loved teaching (and would continue teaching throughout her career), she left Johns Hopkins after nearly 30 years. At the Rockefeller Institute, her job was to lead a group of scientists trying to find a cure for tuberculosis, the leading cause of death in the U.S. at the time. They never found a cure, but their research contributed to new medicines as well as our understanding of cancer.

In 1938, at the age of 67, Florence Sabin retired from the Rockefeller Institute. She returned to Denver so that she could live with her sister and the two women could enjoy retirement together.

Once back in Colorado, instead of retiring, Florence found herself on a path that used her skills in research and teaching for the benefit of her home state. In 1944, Governor John Vivian asked Florence to head a committee on health in Colorado. He had already been criticized for not having any women leading his committees and he hoped the retired old researcher wouldn’t cause him any problems. He didn’t know Florence.

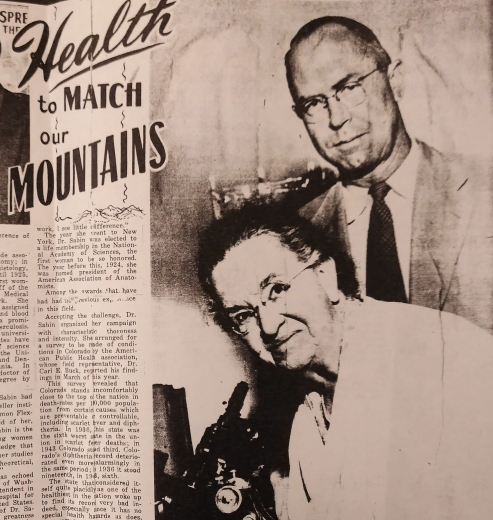

When Florence started into her research on Colorado’s public health, she was shocked by what she learned. People died in Colorado at twice the rate of other states, and many of these deaths were preventable. She learned that the state’s health laws were seriously out-of-date, having last been updated in 1876.

To conduct proper research, Florence visited all 63 counties in the state. She learned about sewage dumped in rivers, unpasteurized milk, and rat infestations that all led to deadly diseases. Florence knew that the laws had to be changed to protect Coloradans and so her committee wrote a set of new health bills, collectively known as the Sabin Health Bills.

She then used her teaching skills to travel the state telling people about the importance of these new health laws and why they needed to be passed. She used the slogan “Health to match our mountains” and convinced voters to fight ranchers and others who feared that the laws would increase their costs. In 1947, nearly all of the Sabin Health Bills passed.

Florence Sabin then turned her sights to Denver. The city didn’t have to adopt the state’s new health laws because of its large population, but as a Denver resident, Florence Sabin was particularly interested in ensuring public health in the city too. When Mayor Quigg Newton asked Florence to take a look at Denver’s health program, she gladly agreed.

She fought to increase trash pick-up, which would reduce the number of rats, and to teach food safety to restaurant employees studying at Emily Griffith Opportunity School. She also pushed for new quality standards for milk and a new sewage treatment plant. One of her most important contributions was a free X-ray program, which could detect tuberculosis in its early stages. These measures cut the rate of tuberculosis in Denver in half. The milk and restaurant safety ratings both increased by about half.

In 1951, at the age of 80, Florence finally retired for good. She continued to receive honors, including when the University of Colorado named their new cancer wing after her. Florence died on October 3, 1953, two years before her sister Mary. In 1958, Sabin World Elementary School in Southwest Denver was named for both of them.

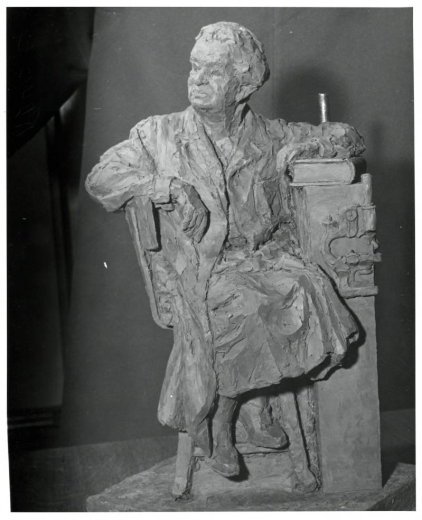

In 1959, Florence was honored again when her statue was placed in the National Statuary Hall in Washington, DC. Each state gets only two statues in the hall, so this honor shows the major impact that this one “woman scientist” had on the state’s health and future.

prestigious - well-known and having respect for being high-quality or successful

women’s movement - a series of political efforts to increase the rights and freedoms of women

nervous system - the system that sends messages for movement and feeling between the brain and the other parts of the body

microscopic - too small to be seen with the human eye

histology - the study of microscopic structures in cells, tissues, and organs

public health - the healthiness of a community or group of people as a whole

unpasteurized - a food or drink that hasn’t been heated for a specific period of time in order to kill most of the harmful bacteria

infestation - having such large numbers as to be dangerous or a problem

Why do you think Dr. Preston told Florence that "any woman who wants to be a doctor must work for women as women, and not alone for herself?” Do you agree?

Why do you think that Florence Sabin was able to continue working until she was 80? Why did she start working again after she “retired” to Colorado?

What do you think was Florence Sabin’s most important research? Why?

Why do you think that Florence Sabin is one of just two Coloradans honored with a statue in Washington, D.C.? Who would you choose for those statues?