In September 1867, the first mention of the word “abortion” appeared in a Colorado newspaper, referring to the termination of a pregnancy. Curiously, it was a passionate screed against the evils of abortion despite the local press having never covered the topic of abortions before. Nonetheless, Dr. F. R. Waggoner referred to a seeming epidemic of underground abortions.

“Medical men, who are sought daily to loan their profession, their skill; for the sacrifice of human life.” Rocky Mountain News September 30, 1867

Wagner was likely inspired by the American Medical Association’s Physicians’ Crusade Against Abortion started by Horatio Storer in the 1850s. Putting aside Waggoner’s overzealous embrace of a largely unsubstantiated moral panic, it was true that abortion had always existed in Colorado, both among Indigenous peoples and American colonizers.

It was common for midwives across time and cultures to provide herbal abortifacients. In the Rocky Mountain West, some common herbs used included Pennyroyal, Soapberry, and Horsebrush. Similarly, regional newspapers in the 19th century were filled with ads for pills to cryptically, “restore menses.” Some of these utilized some of the same herbs used by Indigenous populations, including Pennyroyal, Tansy, and Cotton Root Bark; an abortifacient commonly used among enslaved people in the American South. Unfortunately, the self-administration of these unregulated medications sometimes led to injury and even death, though the numbers of injuries are hard to track considering the private nature of their usage. Likewise, county coroners in Colorado often had trouble identifying the cause of such a death, or were reluctant to list the deceased as an abortion seeker.

For this reason, it is difficult to track the exact number of women and girls who died seeking to terminate a pregnancy, but an attempt has been made to track down all those that were reported on. For most of Colorado’s history, procuring an abortion could bring up to three years in the penitentiary. The earliest press reference to such a crime was simply a mention of J. H. Murphy's arrest in Denver on January 9, 1868, with the charge of abortion.

The first known victim of a botched abortion was a woman in Central City named Maria Casey. Her attending physician, Dr. Aduddell, first claimed she had died from a morphine overdose, but an inquest found that Addudell had prescribed Casey a mixture of Pennyroyal and Tansy after she requested an abortion. After taking the concoction, she became violently ill and died a few days later. Aduddell was charged with procuring an abortion and causing Casey’s death, but the jury was unable to agree on a verdict.

In January 1873, Dr. Mary Solander of Boulder was convicted of manslaughter in the death of Fredricka Baunn. In December 1871, Baunn died suddenly and the coroner determined that her death was the result of an abortion. A Left Hand Canyon neighbor of Baunn led the investigation to Dr. Solander, who had performed the abortion. Solander would become the first woman to be sent to the state penitentiary in Cañon City. Such was the outcry over the verdict that 800 residents of Boulder County signed a petition to the governor, who then pardoned Solander in August 1873. According to an article in the January 1, 1880, Rocky Mountain News, Solander remained the only person to have been sentenced to the penitentiary for the crime of abortion.

In August 1881, Denver Coroner Thomas Linton made the odd claim that he had 56 abortion cases under investigation. While a fetus had been found in Cherry Creek under the Wazee Street bridge and another found buried at Eighteenth and Wynkoop, it was never made clear if these were deliberate abortions or miscarriages and Linton made no further announcements regarding this alleged rash of abortion. Despite the occasional moral panics being stirred by the press, a strongly worded editorial regarding reproductive issues appeared in the July 18, 1883 issue of the Queen Bee, a newspaper founded by Denver suffragists in 1879:

“It is queer, ridiculous and disgusting that men will legislate upon such affairs as infanticide, abortion, etc., and leave questions of caring for the apparent portion of the race with the most shame-faced neglect, and while ever meddling with affairs which should concern women almost exclusively, are talking like dictators to us for parading their defects in management, reminding us often of our sphere of duties. The duty of woman through life should be to see that men do not mar or ruin the fruits of her most precious life work – her apparent sons and daughters.” - Queen Bee July 18, 1883

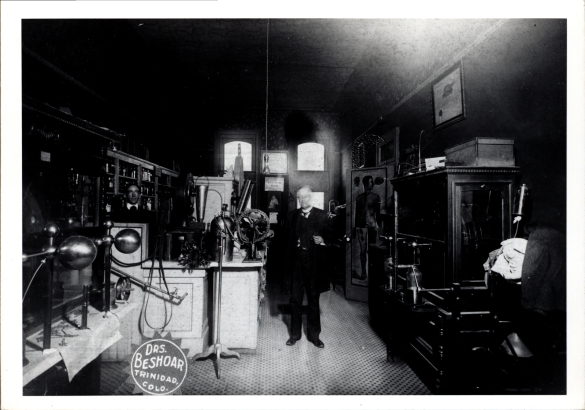

While many of those caught performing abortions were not trained medical doctors, abortion was certainly a part of some medical practices, though less likely to result in a patient’s death. While still done in secret, these doctor-patient interactions were more reminiscent of modern reproductive health care than the headline-grabbing amateur abortions that ended in sepsis and death. Amazing examples of this appear in patient letters sent to Dr. Michael Beshoar, which are part of the Beshoar Family Papers (WH1083).

Dr. Beshoar was a surgeon who settled in Trinidad in 1879 and opened a general practice. Letters from his patients in need of abortion care range from open to subtle and serve as a potent reminder of the plight of women in a world that offered few rights and even fewer options regarding contraceptive options. One particularly poignant letter comes from Mr. Blethen of the Blethen Lumber Company in Aquilar, Colorado.

“Dear Sir, I have to call on you again to help us out again. For God sake doctor, if you have anything you can send me to bring my wife around send me something at once. We are two months past now and it is simply getting unbearable having children come so fast. It is completely ruining my wife’s health and disposition also. This having a baby every year is nearly driving us both wild. So if you possibly can send me something and send enough to do the work.” October 2, 1899

The glimpses at the quiet realities of turn-of-the-century abortion care was not just among the private letters of rural physicians, however. Even official hospital reports would sometimes include abortion numbers as well as individual case studies. The 1900 - 1901 hospital report for the Rocky Mountain Fuel and Iron Company, which had facilities around Colorado, counted 50 abortions performed. They even included the details of an individual case. A 23-year-old woman became deathly ill in the course of her first pregnancy and the doctor, unable to improve her symptoms, induced labor. Her sister-in-law had died seven months into her pregnancy under similar conditions which the doctor suspected to be diphtheria. The document conveys no sense of moral or legal quandaries after providing the necessary care for their patient.

The same year this hospital report was released, the Colorado public was able to see the face of the victim of an illegal abortion for the first time. On January 29, 1901, Dr. F. H. McNaught was summoned to a rooming house at 1353 Champa Street. There he discovered a 24-year-old employee of Joslin’s Dry Goods Company named Maude Mershon. Mershon was suffering from a high fever and was immediately taken to St. Luke’s Hospital. The doctor required Mershon to make a statement in writing implicating the one who had performed the abortion on her in case of her death. She did so and attempts to save her failed. She died like many others due to septicaemia, and the signed statement implicated a woman named Mary Proctor who lived with her husband in an old sanitarium at the corner of Broadway and Jewell Boulevard.

The police initially issued a warrant for Mershon’s longtime boyfriend Walter W. Clark, a baggage checkman at Union Station. He denied having anything to do with the abortion and stated that he and Mershon were engaged to be married. Arthur Mershon, Maude’s brother, testified that Walter and Maude loved each other very much and had indeed planned to wed soon. Proctor was promptly charged with manslaughter. Proctor told police she was too ill to leave her bed and nothing could be found in the local papers regarding Proctor after the initial reporting.

In part two, we look at con-men, crime rings, and attempts at reforming abortion access prior to Roe v Wade.

List of all women known to have died due to illegal abortions in Colorado prior to Roe v Wade.

Note: These are only those victims reported in the press. While abortion deaths were heavily covered by the press, many others were likely not reported by coroners, doctors, and family members.

Comments

I recall an article,…

I recall an article, probably in the Post, from 1977 or so about a young local woman who died from a self-induced abortion using pennyroyal oil. We had never heard of pennyroyal as an abortifacient. I notice that pennyroyal is mentioned in your article. People at the time often drank pennyroyal tea, a very different product from the oil.

Diane, I am not surprised…

Diane, I am not surprised. Many herbal remedy books still promote pennyroyal as an abortifacient. The wrong dosage can often lead to catastrophic outcomes.

I came across this article…

I came across this article while doing some reading while listening to A Public Affair on 8/4/25.

Thank you for providing more context on this important topic to Colorado.

I came across this article…

I came across this article while doing some reading while listening to A Public Affair on 8/4/25.

Thank you for providing more context on this important topic to Colorado.

Add new comment