Imagine only ever seeing zoo animals in cages and yet, for the first time, there’s a BEAR across from you with rocks and trees and a moat, and no visible barrier between you and him. The experience must have been profound. For the North American continent, the first place you could ever have that experience was right here in Denver. Bear Mountain, which is now a historic landmark, was the first nature-based zoo habitat in North America, and a radical departure from the cages that had dominated the scene until then.

Denver’s zoo started in 1896, after the mayor of Denver received a black bear cub as a gift. Because even in the 19th century, bears didn't make ideal pets, the bear was allowed to live at City Park. The “zoo” quickly expanded to include bison, birds, prairie dogs, and wolves, as well as more bears and bear cubs. By 1909, the Denver Zoo was hailed for its scarcity of animal deaths and the place was a hit among tourists.

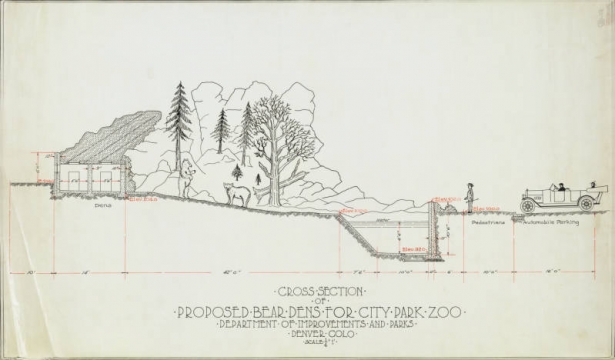

As part of Mayor Speer’s City Beautiful vision for Denver, he imagined a whole new type of zoo: one based on a new trend that had started in Europe. In 1907, German animal trader/trainer Carl Hagenbeck opened his “animal gardens” with a radical new concept: nature-based habitats and no bars between visitors and animals. This mapped perfectly with Speer’s vision. By 1916, landscape architect and city planner Saco Rink DeBoer and zoo superintendent Victor Borcherdt were finally ready to make that vision a reality.

Two years later, Bear Mountain rose above City Park. It was made from plaster casts of cliffs at Dinosaur Mountain and included a steel-and-concrete moat engineered to prevent bears from climbing out to spectators. In perhaps a jealous bit of mud-flinging, Denver's Municipal Facts declared it “the most advanced zoo treatment in the world. [Hagenbach's] work is far inferior because the concrete work there was modeled by hand, does not possess the highly stratified appearance of the Denver work, and is of the same uniform gray color throughout” (June 1918). Clearly, Bear Mountain was intended to be an artistic masterpiece as well as zoological modernization. More images of construction are in our Digital Collections.

Cages were not completely eschewed in the new Denver Zoo, but for large animals, this was a massive change. Even as late as 1926, the city couldn't get enough of Bear Mountain, which it described as the “barless habitat that made the Denver Zoo famous” and “something of an experiment, but it was so immediately and entirely successful that it became the envy of other cities.” The Bear Mountain prototype continues to be a typical model for zoos today on an even grander scale.

As zoos struggle with how to approach habitats into the 21st century, it is easy to forget how much our understanding of animal behavior has evolved and continues to do so. Though Bear Mountain remains a landmark of Denver’s achievement, this was not the end of zoological innovation. Continued research into animal psychology and the effects of these habitats have led to constant changes in Denver and at zoos around the world.

Comments

Thanks, Sarah! Love this

Thanks, Sarah! Love this background history to Bear Mountain. I assume the original bear was caged, prior to getting his new home (although if he were roaming, that would be an image in and of itself).

Regarding your last paragraph, you'll be interested to know that some zoos now will put warming elements under prominently-placed rocks, to encourage large cats to laze about in public view. I believe our zoo has these as well in the lion enclosure.

Thanks for reading and

Thanks for reading and commenting, Laura! I didn't know about the warming elements; what clever use of animal psychology to encourage, not force, a behavior.

Victor Hugo was my great

Victor Hugo was my great grandpa. :)

What a lovely connection!

What a lovely connection! Thanks for reading and sharing, Nathan.

Add new comment