In the early 20th century, Denver jury selection was conducted by a reformed 'criminal' who had once been a part of the city's Curtis Street gambling scene. That reformed criminal was an illegal lottery wheel Denver Police had confiscated from the infamous Inter-Ocean Club, which had been located at 1422 Curtis Street, across the street from where the Denver Auditorium now stands.

How the storied lottery wheel made its way from the Denver Police Department's evidence room to center stage at a formal jury selection ceremony that took place every Saturday morning at the court house, is unclear. But how the wheel was used, and the colorful story of the Inter-Ocean gambling club are spelled out very clearly in a 1931 article from Denver Municipal Facts titled "How Denver's Juries Are Chosen: The Historic Policy Wheel."

Jury selection in this era was an analog process focused on selecting one juror for every 100 Denver residents. In 1931, there were 287,752 Denverites, so 2,878 jurors would be selected to cover trials at Denver's nine courts of record (civil, criminal, county and juvenile). Once the lists of eligible men were prepared, their names would be written on a slip of paper, which was then sealed with a clip, given a number between 1 and 2,878, and placed in the wheel.

Every Saturday (yes, Saturday), the wheel would be pulled out of storage at the Denver County Courthouse and the three seals that had been applied to its three locks the week prior by the Judge of the District Court, the County Clerk and Recorder, and the Jury Commissioner, were broken open and the wheel was unlocked. At that point, a chosen judiciary member would select a pre-determined number of potential jurors based on the number of trials scheduled for the coming week.

While it's not clear when the wheel was first called to this duty, there is plenty of information available about the wheel's original home, the Inter-Ocean Club, the colorful events the wheel must have witnessed there, and its famous former inhabitants. (The Inter-Ocean Club at 1422 Curtis Street should not be confused with the Inter Ocean Hotel located at 1436 16th, which was owned by Barney Ford.)

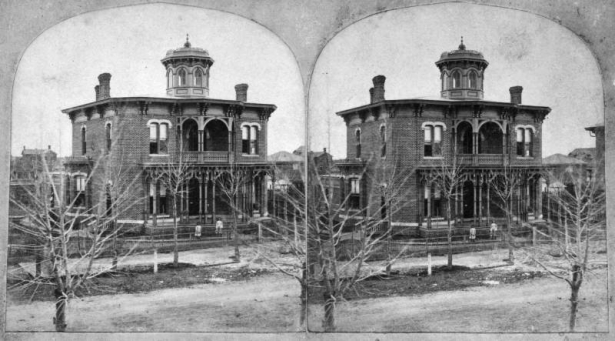

Before Denver's jury wheel ever picked a winner or a juror, the site of the Inter-Ocean Club was the home of Denver merchant William Bradley Daniels, of Daniels & Fisher Department Store fame. After years of maintaining a residence in New York, Daniels moved to Denver to oversee his mercantile operations sometime in 1886. He first appears at 1422 Curtis Street in a Denver city directory in 1887, after an extended stay at the Windsor Hotel.

By 1891, the Daniels family moved on to a larger home and 1422 Curtis Street became occupied by the Arapahoe Wheel Club, one of Denver's first bicycle clubs. The Arapahoe Wheel Club wasn't in the building very long before the space caught the eye of Denver gambling impresario Edward Chase, a.k.a. Denver's "Policy King."

Chase was an early Denver settler who arrived in 1860 at the age of 22 and seems to have been involved in gambling enterprises of one kind or another for most of his life. He's a steady presence in early Denver history and charted a steady rise in power and influence as his operations churned out a continuous river of cash.

In November 1864, Captain Edward Chase was the head of Company F, Third Colorado Calvary when his unit was called to what would become the Sand Creek Massacre. Chase's personal involvement in the massacre is something of a historical mystery. It's known that he resigned from his commission the day of the massacre but the story gets murky from there. He isn't mentioned in any battle reports from that day or subsequent inquiries. The "Policy King" never spoke of the massacre in public or private, so what he saw or did that day is unknown.

On April 27, 1899, an article in the Rocky Mountain News reported that the "Old Daniels House" was going to be Denver's newest gambling hall. The Inter-Ocean Club first appears in Denver City Directories in 1900 and was open - more or less - continuously until 1907.

The Inter-Ocean Club made headlines across the state in February 1900 when James Rice fell down dead while watching a game of faro at the club. Rice's body was left for some period of time before the Inter-Ocean Club players and staff took note. Describing the scene, the Denver Times said, "There was a large crowd in the house and the games rolled merrily along as though such a thing as a police department had never been heard of." Police later found $75 in counterfeit coins in Rice's hotel room.

One of the games that always rolled merrily along at the Inter-Ocean Club was the policy wheel. Policy games or rackets generally refer to any unlicensed lottery, which may offer perfectly legitimate play. Denverites of all stripes happily purchased draws from Chase's policy wheel, which contained 78 numbers and tickets that could be purchased for as little as ten cents. Draws were usually conducted twice a day and a winning ticket could turn a dime into a twenty dollar bill.

The Inter-Ocean Club was part of Denver's very robust turn-of-the-century vice scene, so it's not surprising that incidents like Rice's death caught the eye of anti-vice activists. One activist in particular was the Denver Times, which frequently called for the club's closure and for Denver Police to crack down on open gambling and prostitution.

By 1903, Mayor Robert Speer's administration reluctantly cracked down on Denver's gambling halls in a move that was heralded in the press with headlines like, "Decency rejoices over closing of Denver gambling houses," which ran in the Denver Times. On paper, gambling was done, but in reality, it continued unfettered at the Inter-Ocean until sometime in 1907, when it shut down for good. It's possible that the wheel was seized during this, but it's nearly impossible to be certain. The only time the wheel, or methods of Denver County jury selection appear in DPL records is the previously mentioned May-June, 1931 Municipal Facts article.

In 1907 the building at 1422 Curtis came down and was replaced by several new buildings, all of which were undertaken by the firm of Gaylord & Chase.

A deep dive into courthouse records would likely reveal when Denver's unique policy-wheel-on-a-Saturday system of selection ended, but the fact that a policy wheel with a checkered past became part of jury selection is a fascinating piece of Denver's past.

Comments

Fascinating article!

Fascinating article!

Add new comment