This is the second in a series of “Curator’s Corner” posts: a little peek at the history of pieces in our art exhibit, A Visual Rendezvous: the Art Collection of the Western History and Genealogy Department. Guest Curator Deborah Wadsworth will give us the backstory (and maybe some juicy details) for select pieces that are currently on display on the Central Library’s 7th Floor.

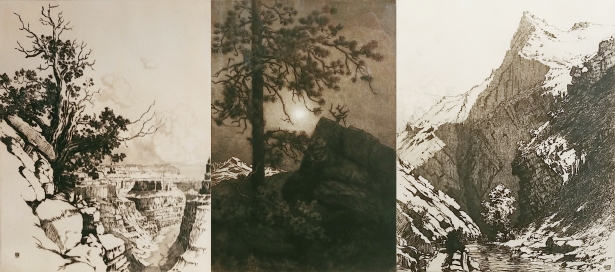

Three subtle and eloquent George Elbert Burr etchings hang near the photographs on the Seventh Floor. They are Canyon Rim, Arizona (C2018-62 ART), Misty Moonlight, Estes Park, Colorado (C2018-63 ART) and Bear Creek Canyon, Denver, Colorado (C2018-61 ART).

Over a lifetime, George Elbert Burr produced an astonishing amount of artwork. He painted over 1000 watercolors and drew tens of thousands of sketches; and pen and ink ;and other drawings. From nearly 400 plates, he printed an estimated 25,000 prints, almost all of which he printed himself. He worked in intaglio, where the design is engraved into the plate to hold the ink, and created drypoints, etchings, color etchings, aquatints and the occasional mezzotint. The A. Reynolds Morse Collection at the Denver Public Library comprises more than 300 Burr works and is arguably the most complete collection in the country.

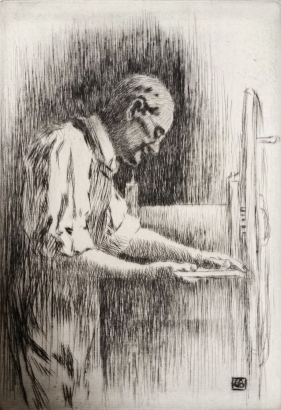

George Elbert Burr was born in Munroe Falls, Ohio, on April 14, 1859. In his childhood, he, “experimented with etching using scraps of zinc from the spark pan under his mother’s stove and printing plates by rolling them through the press used in his father’s store to form downspouts.” He was essentially self-taught. Beyond his mother’s tutoring, his only formal training was three months (or perhaps as little as two weeks) at the Chicago Academy of Design, later the Art Institute of Chicago.

Burr married Elizabeth Rogers, daughter of a minister, in late 1884. Burr and Betty maintained an exceptionally close relationship for over 55 years; they were so inseparable that the family referred to them as a single unit, “Cousin Bert & Betty.” Betty determinedly sheltered him from interruptions and supported his single-minded dedication to his art.

Spending eight years in New York City starting in the late 1880’s, Burr worked as an illustrator for Harper’s and Scribner’s magazines, The Cosmopolitan and Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper. He was able to make a living almost from the beginning. Yet throughout his life, Burr’s poor health badgered him. He never complained and ignored his restrictions as much as possible, even though printing etchings is hard physical work. Burr fought through to personally print almost his entire output.

In 1906, Burr planned to take a group of his paintings on an exhibition tour to Kansas City and Denver. His health was acting up again, so he persuaded a nervous Betty to go in his stead. In Denver, Betty met the Boutwell brothers, local framers and gallery owners. They started up a friendship and business relationship that would last over 35 years. On her return, Betty persuaded Bert to try Colorado for a month. He immediately fell so deeply in love with the area and felt so much healthier that he never returned east.

The Burrs lived first at Brinton Terrace, known as “Denver’s Greenwich Village,” near 16th Street and Broadway. In joining this community where other artists and musicians had studios and the Boutwells had a gallery, they were joining the early-stage Denver art community. Burr actively participated in the community, where his contemporaries included Elizabeth Spalding, Charles Partridge Adams, Anne Evans and Henry Read. In 1909, the Burrs moved to 1325 Logan St., a home Burr designed himself and built in the Craftsman style.

Independent and determined, he rubbed some the wrong way. Burr spurned sales as the goal of his art. He created what appealed to himself, and often refused requests for larger print runs, routinely destroying plates to prevent poor quality overruns. He refused any biographies, saying, “No, it is no business of the public to know of my private life. It is merely curiosity on their part. My work represents my life. It is all that is important.”

By 1924, Burr’s health had further deteriorated and they were obliged to move to warmer Phoenix. They sold their beloved home to the Denver Woman’s Press Club whose stewardship continues to the present.

Burr died in 1939. Faithful to the last, Betty refused to sell Burr’s remaining inventory to dealers, who would have raised his prices. She continued to sell them at the prices he had set. Burr had summed up his life, saying “As long as I can work a little, for the pure joy of it, Mrs. B. and I are happy- in fact we have had fifty years of an ‘Alice in Wonderland’ journey through life. The world has been so kind, I’ve always done just what I enjoyed doing, and never a worry, as the world always gives us more money than we need.”

Today, Burr’s works are held in museums worldwide, including the Smithsonian Institution, Metropolitan Museum of Art, Library of Congress, Bibliotheque Nationale, Fogg Museum, New York Public Library and the Victoria and Albert Museum. DPL’s magnificent collection of Burr prints and originals was donated by A. Reynolds Morse. Morse, a Denver-born industrialist, is well known for his Salvador Dali collection and his Dali Museum in Florida. Like all of the Western art collection, the Morse Burr collection is available for study by the public.

Add new comment