In his book, A Sand County Almanac, conservationist Aldo Leopold wrote a famous quote that goes, "There are some who can live without wild things, and some who cannot." This almanac played a crucial role in the conservation movement and continues to be a fundamental resource for modern-day conservation and environmental thought. Dave Foreman, a renowned conservationist, took inspiration from Leopold's words and dedicated more than fifty years of his life to advocating for conservation and wilderness restoration.

The Early Years

William David Foreman was born on October 18, 1946, to Benjamin A. “Skip” Foreman (1921-1984) and Lorane Juanita Crawford Foreman (1920-1993) in Albuquerque, New Mexico. A fourth-generation New Mexican, “Dave” was the elder sibling of three, with brother Steve born in 1953 and sister Roxanne born in 1955. Foreman’s father Benjamin was a United States Air Force master sergeant who later worked as an air traffic controller, and as a result of his profession the family moved around the U.S. nearly a dozen times during Dave’s childhood. The younger Foreman was very active in conservative politics during his high school and college years. He helped form a chapter of the Young Americans for Freedom in high school, and campaigned for Arizona Senator Barry Goldwater during the politician’s 1964 presidential campaign. After graduating from high school, Foreman attended San Antonio Junior College in Texas, where he formed a chapter of the group Students for Victory in Vietnam. Ultimately, Foreman would transfer to and graduate with a degree in history from the University of New Mexico in 1967.

Following in his father’s footsteps, Foreman enlisted in the military in 1968. He joined the Marine Corps upon finding the Air Force and Navy officer candidate schools full. He quickly realized military life was not a good fit for him, particularly as his difficulty differentiating left from right affected everything from parade ground marching to orienteering, and brought him in for excess hazing. He spent several weeks attempting to be released from the Marines--asserting he was a communist, and claiming he hoped the Viet Cong would win the war--and was eventually put into the brig for 31 days for his various efforts. After just 61 days in the military, Foreman received an administrative undesirable discharge for insubordination. This experience left him temporarily grasping for a new life direction.

The Wilderness Society and RARE I & II

Following his military discharge, Foreman began to teach and labored as a ranch hand in New Mexico. He began river running and backpacking, and through those communities was introduced to active members of the environmental movement such as Dave Seeley, and Black Mesa Defense Fund organizers Jack Loeffler, Bill Brown, and Jimmy Hooper. Foreman returned to Albuquerque and decided to become a career conservationist, joining the New Mexico Wilderness Study Committee. With that organization he coordinated a response to the Gila National Forest Plan, and organized environmentalists to comment at U.S. Forest Service hearings. His work with the Study Committee soon caught the attention of The Wilderness Society, and he was invited to a week-long lobbying seminar in January 1973.

Foreman ultimately joined the Wilderness Society in 1973, as its Southwest Representative responsible for New Mexico and Arizona. He worked at The Wilderness Society from 1973-1979, and during this time the largest project he contributed to was the Roadless Area Review and Evaluation II (RARE II) environmental statement.

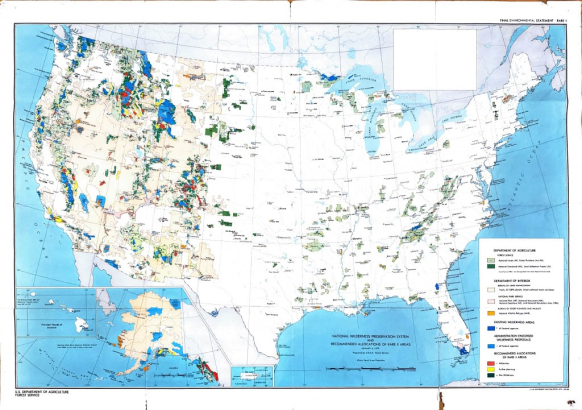

The RARE I and II projects had come about as a result of the 1964 Wilderness Act, which called for a large-scale inventory of national forest land to be completed by the U.S. Forest Service as part of its mandated wilderness review. At the time the Wilderness Act was passed, there was no comprehensive understanding or inventory of the wilderness lands held by the federal government. RARE I began in 1967, with the goal of inventorying federal land that could be designated as wilderness. Such a designation would provide lasting protection for roadless areas within the National Forest System.

The RARE I project culminated in a 1972 report that identified 12,300,000 acres suitable to be designated as wilderness, far less than conservationists thought should be considered eligible. Unfortunately, federal courts soon determined the report findings did not comply with regulations of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA), and the RARE I inventory was scrapped. As a response, the U.S. Forest Service initiated RARE II in 1977. This second report recommended 15,000,000 acres of national forest land be designated as wilderness, and identified an additional 10,800,000 acres to be further studied, again far less than conservationists thought should be included. RARE II was also challenged in the courts and much of it was later voided.

Foreman was heavily involved in the RARE II project, helping to scout areas in the Southwest and lobbying in Washington for areas that should be considered for wilderness designation. His time as a lobbyist would ultimately cause him to leave the Wilderness Society organization, disillusioned and critical of agencies such as the U.S. Forest Service, Bureau of Land Management, and the U.S. Department of Agriculture. He came to believe these government agencies were too amenable to working with profit-driven petrochemical, logging, and mining industries. Foreman also disagreed with new leadership changes at The Wilderness Society, seeing them as more business-oriented choices, and less about preserving wilderness. Ultimately, he believed organizations such as the Sierra Club, Friends of the Earth, and the Wilderness Society were ineffective in preventing widespread environmental destruction. They were, he thought, far too compromising. Most importantly, his time in Washington, D.C. showed Foreman that his own skills were more in line with grassroots organizing on the ground, than on the Hill.

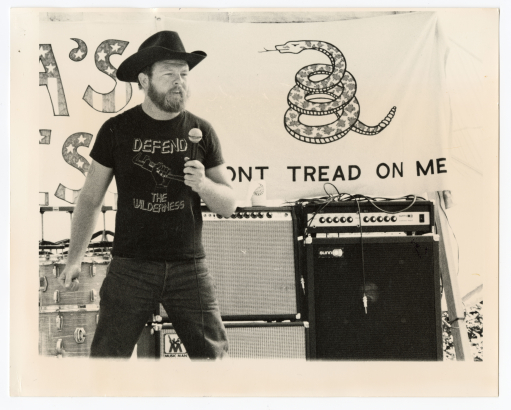

Earth First! Defending Mother Earth

In 1980, following a hike through the Mexican Pinacate desert, Foreman and his friends Mike Roselle, Howie Wolke, Bart Koehler, and Ron Kezar formed Earth First!. Their goal was to create an environmental group that could take direct action, and was led by the motto, “No compromise in defense of Mother Earth.” Members of the organization were responsible for organizing protests and demonstrations, overseeing fundraisers and letter-writing campaigns, drafting and submitting environmental proposals, and contributing public comments about environmental decisions.

As part of the foundational tenets, the Earth First! the organization did not support a human-centered worldview and argued that all parts of the planet’s ecosystems are vital for life on Earth to exist. Spiritually, they believed that wilderness, clean air, and animals are all vital for humans to be healthy. The group believed that dramatic direct action was necessary to draw increased attention to environmental crises.

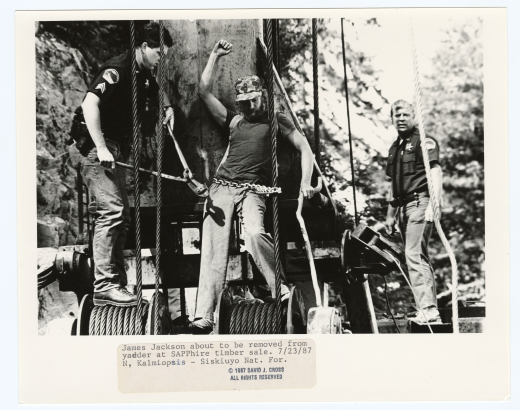

The activist group was uniquely organized in a non-hierarchical fashion, rejecting “professional staff” and formal leadership, and eschewing the idea of having “members,” opting instead to call adherents “Earth First!ers.” Rejecting a hierarchical bureaucracy was intended to strengthen their ability to participate in direct action without getting bogged down in committees and planning. The founders also chose a variety of tactics to achieve their political means, including grassroots and legal organizing, civil disobedience, and even monkeywrenching (or non-violent sabotage of projects and companies seen to exploit the environment). Some of their direct actions included protests at national parks, removing survey markers, damaging logging and construction equipment, and tree spiking (tree spiking was the controversial practice of driving metal spikes into trees to damage chainsaws, thereby preventing loggers from cutting them down).

The group eventually expanded to several domestic and international branches, located as far afield as Australia and New Zealand, India, Europe, Asia, and Africa. The group also developed two regular publications: the Earth First! Journal and the Earth First! Calendar. Foreman was the editor of the Earth First! Journal from 1982-1988.

Beginning in the late 1980s, the FBI began investigating Earth First!, specifically co-founder Dave Foreman and his associates. As part of the investigation, one agent named Michael Fain (alias Michael Tait) infiltrated the organization and recorded conversations with members. This government scrutiny culminated in the 1989 arrest of Dave Foreman and four other Earth First! members on charges of conspiring to damage power lines in Arizona. The arrested parties were tried in the subsequent court case United States v. Dave Foreman and came to be known as the "Arizona Five.” In the end, tapes revealed that the FBI didn’t have anything substantive on Foreman, but they continued their pressure. Foreman eventually agreed to a plea deal that reduced and eventually dropped the charges against him, while the other Arizona Five members served jail time. Stress from the legal proceedings created enough fractures within the group that Foreman and his wife Nancy Morton left the organization in 1990. The Earth First! organization continues to operate to this day.

From Protests to Rewilding

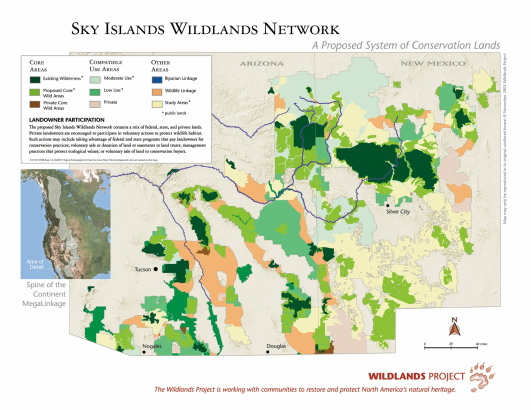

Foreman had been questioning EF! strategy for a while and, and soon regrouped to adjust his approach to environmental activism and wildlands design. His ecological philosophy had been rooted in “deep ecology,” or the belief that nature has inherent value that should take precedence over monetary or other human values. In 1992, Foreman coined the term “rewilding,” and much of his remaining career was devoted to advocating for its implementation. This term stood for restoring sustainable ecosystems on a continental, interconnected scale through a variety of conservation efforts (as opposed to focusing on protecting one species or habitat, for example). Among these efforts were the “Three C’s”: cores, corridors, and carnivores. The model proposed propping up biodiversity support, reintroduction of apex carnivores and other focal species into areas where they had been removed, and the expansion of protected, human-free wilderness areas. Foreman’s philosophy also supported drastic limits on immigration to the U.S., a stance which led many to accuse him of xenophobia and anti-immigrant sentiment.

In 1991, Foreman, Douglas Tompkins, and Dr. Michael E. Soulé co-founded the North American Wilderness Recovery Strategy, which was later renamed the “Wildlands Project” (TWP). The organization was a think tank seeking to prevent biodiversity loss and enhance climate change resilience. Their conservation scientists published research papers and designed rewilding maps and modeling for four “Wildways,” or protected wildlife corridors, spanning the North American continent. These corridors included the Atlantic coastline, the Pacific coastline, the Canadian arctic and boreal forest, and the “Spine of the Continent,” which followed the Rocky Mountains from the Canadian Yukon all the way through the southern tip of Mexico. The Wildlands Project advocated for drafting a protective policy to create protected wildlife reserves within the four cores.

While the organization originally focused on North America, they quickly expanded to include projects and political activism scoped to a variety of levels, including partnering with other conservation groups both local and international. In 2009, the organization was renamed "Wildlands Network," a name it maintains today.

Foreman was a frequent contributor to the Wildlands Project’s publication, Wild Earth, a quarterly magazine founded by Foreman and John Davis. The magazine was published from 1991-2004 and featured Foreman’s “Around the Campfire” column.

In 2003, Foreman left the Wildlands Project to found another think tank, the Rewilding Institute (TRI). His message continued to focus on managing human population growth, and on advocating for wildland preservation through the aforementioned 3C’s rewilding approach. He moved his “Around the Campfire” column to the Rewilding Institute website. Closer to home, Foreman was also involved with creating the New Mexico Wilderness Alliance (now New Mexico Wild).

Prolific Author & Speaker

In addition to his work as an activist and organizer, Foreman served on the Sierra Club’s Board of Directors from 1996-1998, but left the organization due to differences of opinion on overpopulation. He presented at conferences and private events on conservation issues and was a prolific author of twelve books on conservation and wilderness topics.

Among his many publications, Foreman authored and edited several titles that include Ecodefense: A Field Guide to Monkeywrenching (ed. 1985, with Bill Haywood); The Big Outside (1989, authored with Howie Wolke); Confessions of an Eco-Warrior (1991); Rewilding North America (2004); Manswarm and the Killing of Wildlife (2011, and second edition with Laura Carroll, 2015); Take Back Conservation (2012); and The Great Conservation Divide (2014). He also wrote a fiction book called The Lobo Outback Funeral Home (2000). Foreman also wrote the aforementioned regular column “Around the Campfire,” which began in the Earth First! Journal, then later continued in Wild Earth and on the Rewilding Institute website.

In 1976, Foreman married Sierra Club conservationist Debbie K. Sease, but the marriage later ended in divorce. In 1986, he married Nancy Morton, a medical professional and wilderness first aid expert. She worked as an ICU nurse, then taught at the University of New Mexico School of Nursing for 22 years. Foreman and Morton remained together until she died on January 16, 2021. Dave Foreman died from interstitial lung disease in Albuquerque, New Mexico, on September 19, 2022. Foreman was survived by his sister Roxanne Pacheco, two nephews, a niece, and two beloved cats.

Sources cited:

Dave Foreman Papers, CONS223, Conservation Collection, Denver Public Library

Conservation Collection, Denver Public Library

Other related resources:

Wilderness Society Records, CONS130, Conservation Collection, Denver Public Library

Add new comment