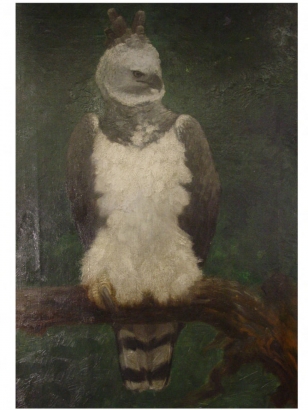

The art collection at the Denver Public Library's Western History and Genealogy Department is frequently, and accurately, described as a hidden gem. But inside that hidden gem are even more hidden gems that WHG staff run across on a regular basis, that includes this jewel, titled Male Harpy Eagle (C72-5 ART) from Robert K. Knight.

While most of us have probably never heard of Knight, it's likely that all of us have been profoundly influenced by his work. Knight (1874-1954), was a New York-born artist who made his living primarily by painting realistic depictions of dinosaurs for museums across the country, including the Denver Museum of Nature and Science. In doing so, Knight laid the foundation for how many of us visualize extinct creatures.

How influential was Knight? In a 2018 article in the Scientist titled, "Charles R. Knight’s illustrations shaped the public’s view of prehistoric life," Field Museum Curator Pete Makovicky said, "He really had a huge impact on how the public perceived paleontology, because most people are interested in some sort of educated estimate of what these things would have looked like in life—bones are inspiring, but they are not quite enough." And if anyone would have known what is inspiring in a museum it was Knight.

At the age of 12, Knight enrolled in the Metropolitan Art School, which is actually housed in the basement of the Metropolitan Museum of Art. Securing a position at the school was an impressive achievement for any 12-year-old, but it was all the more impressive for Knight, who experienced both severe nearsightedness and an eye injury that left him legally blind. Knight compensated for these issues by painting with his face closer to the canvas than the average artist would.

Throughout his early years, Knight spent innumerable hours in natural history museums sketching animals (particularly birds) and honing his skills for a career he didn't even know he would have. His efforts eventually caught the attention of a paleontologist at the American Museum of Natural Science who commissioned Knight to paint a depiction of an enteledon, a kind of prehistoric pig. The challenge, of course, is that no one has ever seen an enteledon and Knight would be working solely from fossilized bones.

Knight's depiction of the enteledon drew praise from museum staff and opened a world of new opportunities for the up-and-coming artist. From that point on, the bulk of his work would be depictions of extinct creatures.

What made Knight's work stand out from other practitioners of Paleoart was his depiction of dinosaurs as dynamic creatures. His dinosaurs ran, fought, and practically jumped off the canvas. This was a far cry from the dry, anatomical depictions that dominated the field up to that point. In showing dinosaurs as realistically as possible, Knight imprinted his vision on generations of dinosaur fans, both amateur and professional.

Not just dinosaurs

While dinosaurs dominated Knight's oeuvre, other elements of the natural world made their way into his paintings, particularly birds. That's where the painting held by WHG comes into the picture. Although the male harpy eagle looks like something from another age, it's an animal that's very much still with us. Found mostly in the tropics of South America, the harpy eagle is one of the largest eagle species on the planet.

Now why, exactly, did this painting make its way into the DPL Art Collection? We don't really know. We can tell from its accession number C72-5 ART, that it was purchased in 1972, but was painted in 1901. Regardless of the reasoning behind the acquisition, DPL is fortunate to have an original piece from such an impactful artist.

And the next time you picture a dinosaur in your mind, remember that your vision may well have been imprinted by Knight's work.

Add new comment