In the spirit of American Archives Month, this October we’ve compiled a three-blog series about what archivists do and how we make collections accessible.

From the moment each archival collection arrives in the library there are a series of way stations it passes through, moving it from the initial donation to making it accessible for our researchers. Last week’s post walked us through the acquisitions decision, and you can read more about that here. The next stations on our journey are processing and cataloging.

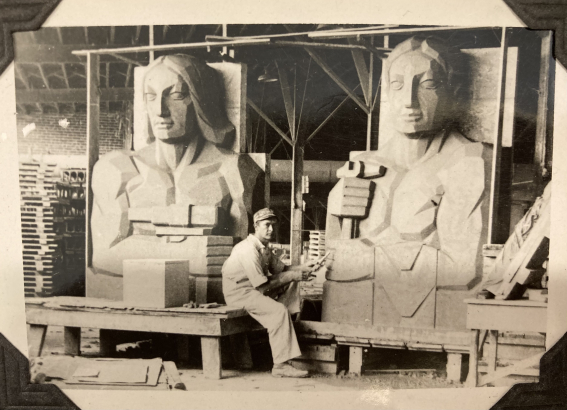

When a collection is placed into our care, we do an initial review of its contents, both physical and topical. We record information about the collection and donor — from biographical information to the number of boxes or items — and we then begin processing the materials.

“Processing” is the work that is done to organize the materials in a collection, identify significant people or events covered, and create a menu of sorts — called a research guide — listing the contents and location of materials. The processing phase is also when any necessary conservation or preservation efforts might be implemented.

With larger manuscript and photo collections, processing efforts can take years, but with the Julius P. Ambrusch Terra Cotta photograph album we discussed in our last post, it was a matter of just about a day. As an intact photo album, the collection did not need to be organized (no messy papers), and the archivist determined it was in good physical condition for an item of its age. The album did not require much special attention. In short:

- The photos were stable and largely still attached. Photos facing each other did not appear to be causing damage

- The paper the photos are affixed to was not acidic and did not need flattening or repair

- The binding was sturdy enough that the album did not require rebinding, or special handmade housing.

As far as physical preservation efforts, our archivist placed a few loose photos that had come free from their mooring into archival-quality polypropylene sleeves. She also housed both album and photo sleeves in an archival box where they sit snugly (but not too tight!).

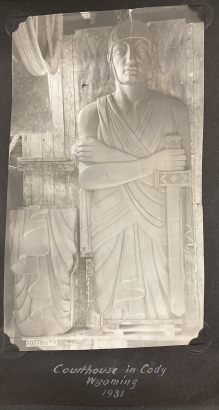

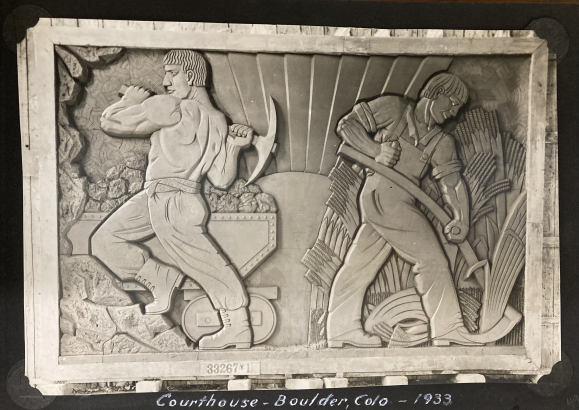

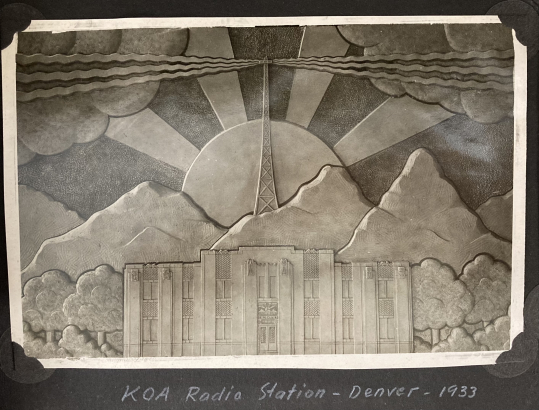

Turning to the information contained within the collection, our archivist noted there are a number of photos documenting terra cotta projects gracing buildings that still stand. These include friezes for beautiful Art Deco structures like the Boulder County Courthouse (built 1933, seen above) and the former KOA Radio Station (now CDOT building) at Colfax and Tower Road (built 1934, below).

As very few researchers would request to see an item listed merely as “a photo album” our archivist knew it was key to describe the contents themselves. While describing every item in a collection is impractical with larger collections, the simple nature of this one allowed her more time for indexing. A look at the final collection guide she created will show that each photograph is listed and succinctly described. Researchers using our archives research tool can now discover exactly what exists, and where to find it.

Following processing and indexing, the next station on the Terra Cotta photo album's journey will be cataloging. Our archivist has handed the collection over to our special collections cataloger, who will further research Julius P. Ambrusch and the studio where he worked. He will create a catalog record for the collection that contains a biographical summary, a brief description of the contents, and a link to the more detailed collection guide.

Our cataloger will also assign Library of Congress subject headings (LCSH) to the catalog record. These subject headings have been developed and edited by librarians over the past 110 years to describe what a collection or book is about. They are shared by libraries worldwide, and are how a subject search in the library catalog produces a list of items. Historically LC subject headings have also skewed towards a white, Christian, heterosexual viewpoint, and so our cataloger is also mindful of assigning or altering terms to be more inclusive and respectful than one might have seen in the past.

Once the bulk of the “heavy lifting” is done, staff will select a final shelf location, affix labels to the box, and the item is then ready for public discovery and use.

For many collections, the process stops there. With collections that have particularly unique or beautiful images, we may also choose to digitize images for our online collection. That process will be covered in our third installment of this series.

This blog is part of a series in honor of American Archives Month. Read all three parts to follow the album and learn about other archival work.

- Acquisition

- Processing and Cataloging (you are here)

- Digitization

Comments

Laura, thank you for

Laura, thank you for presenting about the Denver Public Library Western History and Genealogy Department's resources for The Colorado Genealogical Society. It was fun getting to "see" you again. (At least virtually on zoom) I remembered that I had met you through the craft events through History Colorado at the Byers-Evans House. I was not aware (or may have forgotten) that you changed from working for History Colorado to working for the Denver Public Library.

Hi Carrie! Thanks for your

Hi Carrie! Thanks for your message. I recognized your name from before, so am glad to hear from you again. I hope the Genealogy program was helpful! Let us know if you have any questions.

Add new comment