Nowadays the streets of West Colfax are filled with shopping centers, healthcare facilities and commercial offices that blend with residences in this Hispanic and Asian multi-ethnic neighborhood. However, more than 100 years ago, West Colfax developed as the residential and commercial home of Denver’s original Jewish population.

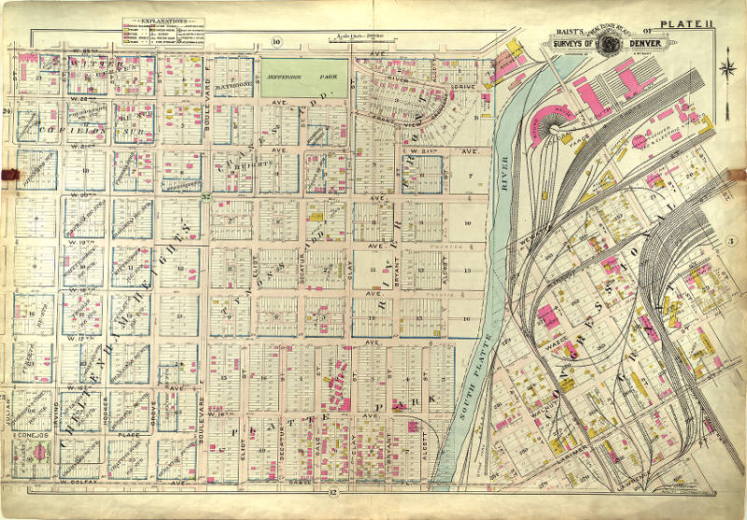

West Colfax has been home to various Denver communities from the late-nineteenth century, and since that time has seen its fortunes wax and wane. Bounded by Federal Boulevard (east), Sheridan Boulevard (west), West 17th and 19th Avenues (north), and 10th Avenue and Dry Creek in the Lakewood Dry Gulch (south), West Colfax is contiguous with several other West Denver neighborhoods, including Villa Park, Barnum (East and West), Sloan Lake, and Sun Valley.

But contemporary West Colfax is less defined by its boundaries than its namesake street, and the relationship between a residential neighborhood and a hard-luck commercial stretch of America’s longest street. Originally known as Golden Road for its connection of Golden and Denver, Colfax was renamed in 1896 for Schuyler Colfax, vice-president to President Ulysses S. Grant. Today, Colfax is a 26-mile-long strip that extends from Aurora in the east, west to the mountains through Denver, Lakewood, and Golden. Charles Linn, writing in Architectural Record, compares a contemporary view along the length of Colfax as “a bit like looking at a gigantic core sample. One can almost view the complete history of this Rocky Mountain city along its length and see how it has prospered, declined, and in some cases, has been renewed.”

Colfax long served as a route for travel and trade through Denver. Westward travelers used the Golden Road as a way to the mountains, meeting wagons of hay and other agricultural goods destined for Denver. Travelers traversed a section of the Front Range with few residents, save for a handful of grand residences, shanties, and farms. But in the late-nineteenth century, new arrivals began to settle and establish homes and business in the vacant lands west of the South Platte River, including the small residential development of gracious Victorian homes first established in 1891 by developer Ralph Voorhees, and later known the Stuart Street historic district. By 1892, a street railroad crossed the Larimer Street bridge, and thereafter extended to Sheridan Boulevard, spurring the creation of new residential neighborhoods in West Denver, and business development along a western span of Colfax Avenue. In 1891, one group of interested citizens succeeded in establishing Colfax as a town distinct from Denver. Another group, largely associated with business interests along Golden Road and desirous of annexation by Denver, seceded and established themselves as Brooklyn in 1892, a town just nine blocks in length, and two-and-a-half blocks wide. Brooklyn, as Westside historian Ida Libert Uchill has observed, would have “a short past, six months of hectic present, and absolutely no future.” Within a year the division was reconciled, and the West Colfax neighborhood was incorporated into the city of Denver in 1897.

With the turn of the century, West Colfax and other Westside neighborhoods were fast becoming the heart of a vibrant, working-class community. With immigrants from the eastern United States, as well as more recent arrivals from central and eastern Europe, the neighborhood of modest homes and small businesses was a distinctly Jewish community, although one that observers found quite unlike others in the crowded urban neighborhoods of the eastern United States. But by the 1950s, West Colfax’s Jewish community had begun to disperse throughout the city. In 2000, Gertrude Hyman, owner of the Lake Steam Baths, a fixture of West Colfax community life since its construction in 1927, recalled the remove of Jewish families and their dispersion throughout metropolitan Denver, and characterized it as an exodus. Nevertheless, the family-owned and operated baths endure. And a strong community exists around the Congregation Zera Abraham synagogue, along with other significant institutions of Jewish Denver, such as Yeshiva Toras Chaim and Beth Jacob High School.

In the early post-World War II era, Colfax was a vital East-to-West avenue, especially for those intent on a mountain vacation or recreation. Much of Colfax became a seat of hotels and motels, restaurants, and entertainment spots, where travelers and residents alike might rest, eat, and be entertained. Development of Colfax seen in the 1930s, when the street was designated U.S. Highway 40, paled in comparison to the boom in construction during the 1940s, including a spate of motels, restaurants, and clubs from the 4400 block of Colfax through Lakewood. But with this new, automobile-oriented face to Colfax Avenue, several of the causes for its subsequent decline were put in place. Colfax was widened, and widened again, and again, to accommodate increased automobile traffic, and boulevards were lost to new lanes of traffic. Businesses were oriented to those who traveled by car, not those on foot from within a neighborhood. With the construction of the interstate system, travelers no longer used Colfax as means of passing through Denver to destinations east or west, and the short-lived golden age of Colfax Avenue passed. Unfortunate zoning, loss of trade, and a less-than-hospitable pedestrian environment further contributed to decline.

Much of the recent history of West Colfax has been concerned with a series of revitalization efforts, beginning in 1978 with a study of the street itself and the means to create a more inviting environment. A succession of studies, general plans for development, and a subsequent return to a need for study and revitalization efforts have marked the area for more than thirty years. To some in Denver’s West Colfax community, Lakewood’s efforts to revitalize its portion of the commercial strip have seemed more concerted and effective, and a contrast has been drawn with what is perceived as Denver’s relative neglect.

Today, West Colfax is identified by the Piton Foundation as one of the city’s at-risk neighborhoods, with residents who are younger, poorer, and less educated than those who reside in almost any other Denver neighborhood. According to the 2000 federal Census, some 70% of West Colfax residents are Hispanic; 20% are White; and the remainder are a mix of individuals who designate themselves as “other races” or Black. Some 40% of West Colfax residents are without a high school diploma, twice the city-wide rate of 20%, and just 10% of residents hold an undergraduate degree, one-fourth the rate of Denver’s population. But, as a recent study suggests, West Colfax is also a neighborhood of diverse households -- poor, rich, and the degrees between -- who have decided to make it home, and one local publication recently designated it as a up-and-coming city neighborhood. Light rail construction, redevelopment of St. Anthony Central Hospital, a new library decades after the closure of the beloved Dickinson branch, and the neighborhood’s proximity to downtown jobs and amenities offer the prospect of renaissance.

Located on the western edge of Denver, the West Colfax neighborhood is dissected by West Colfax Avenue thus giving the neighborhood its name. With Federal as the eastern boundary, West 12th Avenue as the south, North Sheridan Boulevard on the west, and Sloan Lake and West 19th Avenue on the north, West Colfax encompasses a wide variety of residences, businesses, and civic buildings.

Denver’s East European Jewish population began with a trickle in the 1870s, but this early group was soon augmented by a major influx of Russian Jews in the 1880s. Many were part of a larger immigration fleeing economic hardships and religious discrimination in Russia and were attracted by the promise of new opportunities in America, known in Yiddish as the Goldineh Medinah or the “Golden Land.” To alleviate the resulting problems of overcrowding and poverty in major eastern urban centers, some Jews were encouraged to go west.

In 1882, fifty Russian immigrants arrived in Cotopaxi, Colorado, to pursue their dream of farming, an occupation long denied to them in their homeland. However, within two years the settlement was abandoned, and many of the colonists, including members of the Shames, Milstein, and Grimes families, made Denver their new home, settling in the west-side immigrant enclave (first located along the Platte River, and then gradually expanding and moving westward) with other East European Jews, working primarily as peddlers and small shopkeepers. Shul-Baer Milstein, the patriarch of the Cotopaxi colony (although he was not an actual colonist himself), and his wife and seven children came to Denver in 1883. Milstein found success in the cattle business and became one of the founders of the first synagogue in West Colfax, Congregation Zera Abraham, organized in 1887 and first located near the Platte. Ed Grimes, the young Cotopaxi colonist who walked to Denver in 1883, later served as the congregation’s first president. Congregation Zera Abraham is the only one of the early neighborhood synagogues that remains in existence and active today. Its second location was farther west at the former home of the Jewish Labor Lyceum on Julian Street before moving to its present home on Winona Court off of West Colfax Avenue.

Before long the area was filled with numerous small synagogues, modest businesses, particularly those who catered to the mostly Orthodox Jewish immigrants (such as kosher bakeries, grocery stores, and meat markets), and many Jewish social and welfare organizations. Cook’s Baths and a Yiddish theater also flourished in the neighborhood for many years. Many young Jewish boys (and a few girls!) provided the bulk of Denver’s “newsies,” who hawked newspapers on Denver’s corners to earn a few dollars to help augment modest family incomes.

The Jewish section was comprised of well over 1,500 individuals by 1904, and over the next decades Jewish stores almost exclusively dotted West Colfax Avenue from Federal to Sheridan Boulevards. In many ways the area mirrored New York City’s famous Lower East Side, a largely Jewish neighborhood, yet as one observer commented it was a far cry from the typical urban ghetto and exhibited a distinct open western flavor. In a 1904 study, Dr. Maurice Fishberg, head physician for the United Hebrew Charities of New York asserted, "The homes of the poor living here [in Denver’s West Colfax area] are as a rule tidy and clean, nothing like the overcrowding seen in Jewish quarters in New York or Chicago. The environment here looks more like that of the average small western town, than like a Jewish district of Europe.”

The small immigrant Jewish community was largely composed of people of very modest means but they were centrally involved in philanthropy, and a myriad of Jewish benevolent societies such as the Chesed Shel Emes (True Loving Kindness) Society, which provided free burials, flourished. A large Hebrew School for Jewish children, the Yeshivas Etz Chaim Talmud Torah, was established in 1910. Channah Milstein, a Russian Jewish immigrant and a former colonist at Cotopaxi, was known for her extraordinary personal commitment to charity. For many years, she was a fixture in the West Colfax immigrant community as she relentlessly urged local residents to contribute to her collections for the needy. Mary Kobey, originally from Poland, was a traditionally observant Jewish midwife in Denver who earned the nickname “Denver’s Angel of Mercy” for her selfless concern for poor new mothers in the immigrant Jewish community. She volunteered her services at no charge to those who could not afford to pay and was frequently seen collecting money and clothing for baby layettes from merchants in the area.

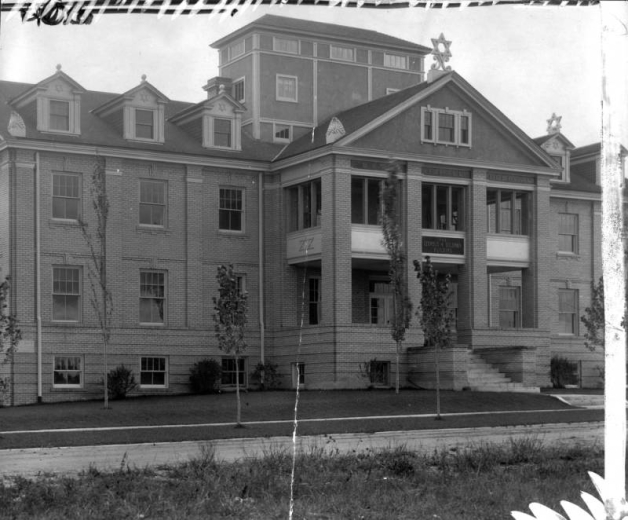

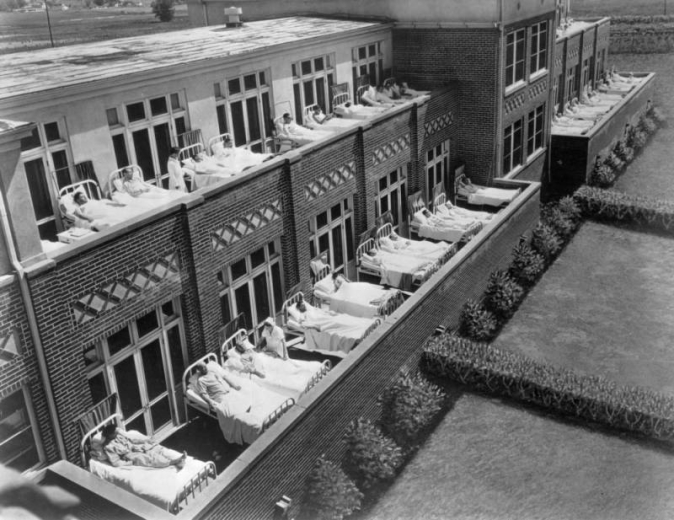

In the early 1900s, the West Colfax Jewish immigrant neighborhood was also augmented by an influx of impoverished immigrant Jews who came to “chase the cure” to seek a remedy for tuberculosis, the leading cause of death in the United States at that time. Colorado, with its dry and sunny climate, drew tuberculosis victims like a magnet and soon earned the nickname of “The World’s Sanatorium.” Since no publicly supported institutions for consumptives existed at the turn of the century, the challenge of adequate care for these people was left to private institutions. The Jewish community was the first to come to their aid with the founding of the formally non-sectarian National Jewish Hospital for Consumptives, which opened in 1899. Founded largely by acculturated, well-to-do German Reform Jews in Denver, the sanatorium treated all patients free of charge. Its motto was “None May Enter Who Can Pay, None Can Pay Who Enter,” reflecting its benevolent origins. However, NJH generally treated only patients with incipient tuberculosis and lacked a kosher kitchen in the early years. Moreover, many of the East European immigrant Jews felt their German co-religionists often acted in a condescending manner to the newcomers who brought with them their “Old World” manners, language, religious customs, and dress.

In 1903, a group of Jewish working class immigrants in the West Colfax neighborhood banded together to form the Jewish Consumptives' Relief Society to treat patients in all stages of the disease in a more Jewish environment, and managed to raise the money to launch the institution. They were joined by several prominent local Jewish east European physicians, most notably Dr. Charles Spivak, who served as the executive secretary of the JCRS from 1904 until his death in 1927, and Dr. Philip Hillkowitz, who served as president of the JCRS from 1904 until his death in 1948. Dr. Hillkowitz’s father, Rabbi Elias Hillkowitz was regarded as the “dean” of the west side Orthodox Jewish rabbis in the early years of the twentieth century.

The JCRS opened its doors in September of 1904 with seven patients housed in white wooden tent-cottages to maximize their exposure to fresh air. Animated by traditional Jewish imperatives of tzedakah (commonly translated as charity but more literally meaning justice), its motto “He Who Saves One Life Saves the World,” taken from the Talmud, personified its philosophy. Over the next fifty years, the JCRS provided all of its services free of charge and 10,000 patients would pass through its doors before it changed its mission to cancer treatment. It was formally non-sectarian, but for its first decades the majority of patients at the institution (as was the case at NJH) were east European Jews, who helped swell Denver’s Jewish population, which rose to about 15,000 by 1912. Located on West Colfax Avenue in Lakewood, Colorado, the JCRS sanatorium served as a beacon of hope to thousands of victims of tuberculosis from throughout the United States.

Not only did the Denver Jewish community care for its sick, but it also extended its concern to the children of tuberculosis patients. In 1907, under the guiding spirit of Fannie Lorber and Bessie Willens, the Denver Sheltering Home for Jewish Children was founded on the West Side and evolved into a large complex at 19th and Julian Streets. Over the years, as tuberculosis became less of a threat, it changed its name several times and in 1939 was renamed the National Home for Asthmatic Children. It merged with National Jewish Medical and Research Center in the 1980s and won national acclaim for its asthma treatment program. The Jewish community also established the Beth Israel Old Folks Home and Hospital in the 1920s. The buildings were taken over by St. Anthony Hospital in the 1990s, and Beth Israel moved and was transformed into Shalom Park in Aurora.

Through the 1930s and 1940s, the Westside neighborhood remained heavily populated with Jewish residents, and the Colfax Viaduct was said to have been jokingly referred to as the “Jewish Passover.” As the West Colfax immigrants became Americanized and their children passed through the American education system via Cheltenham Elementary and the popular Dickinson Branch Library, succeeding generations entered professions or other businesses and became Denver community leaders. Many of the small synagogues ceased to exist and Congregation Zera Abraham and the Hebrew Educational Alliance, a more modern Orthodox synagogue, dominated the neighborhood. A number of residents moved to more upscale neighborhoods in other parts of Denver and the suburbs. Following the migration trend, the HEA moved to the southeast, but today a strong core of Orthodox Jews still anchors the neighborhood, which now hosts a Yeshiva high school and graduate school for advanced Jewish education and a Jewish girls' high school. Although the Jewish population numbers are smaller today then they were a century ago, the spirit of Jewish benevolence and traditional observance still unite the close-knit community, heir to the traditions of the first Jews who settled in the area.

by Dr. Jeanne Abrams, Director of the Peryle H. and Ira M. Beck Memorial Archives Beck Archives

Ms. Nettie Moore is a legend in the West Colfax neighborhood. She has been a resident and activist in the community for more than 80 years. According to all accounts, she has pioneered progress in the neighborhood and improved the quality of life for everyone. Her story is an important part of the story of the West Colfax neighborhood.

She was born Nettie Catherine St. Clair Pacetti on December 22, 1924. Her family moved to Colorado while she was still an infant and eventually settled into a home on Utica Street just west of downtown Denver. At that time the area was mostly rural, with plenty of room for horses, chickens and vegetable gardens. They did not have electricity or indoor toilets. Nettie completed her schooling at nearby Colfax Elementary School, then Lake Jr. High School and later graduated from West High School. In 1945, Nettie married her high school sweetheart, Dick Moore. Together they watched the West Colfax neighborhood grow and expand as more and more homes were built, businesses were established and generations of families moved in and out.

As part of her commitment to the community, Nettie served as the lunchroom manager in the Denver Public schools for nearly 30 years. In addition, over the years she has fought passionately for neighborhood improvements including sidewalks, curbs, paved streets, lights and transportation. As an acknowledgement of her tireless efforts to create a safe and viable West Colfax, both a park and apartment building are named after Nettie, ensuring that her name and hopefully, her legacy, live beyond her lifetime. The West Colfax neighborhood is truly a better place because of Nettie Moore.

For more information about this remarkable woman, visit North Denver News to read an article.