Washington Park is the prime attraction in the neighborhood bearing its name, a lush retreat that is well-appreciated by both people who live close by and people coming from far away. Reinhard Schuetze laid out this scenic park in the grand Victorian manner in 1889. It features two beautiful lakes; the largest meadow in the Denver park system; a remnant of the City Ditch (which was essential to the watering and hence the development of the park); a forested hill graded by the Olmsted Brothers and planted by DeBoer; romantic deciduous tree plantings; the largest formal summer flower beds in the Denver park and parkway system; and important architectural embellishments such as the 1913 Boat House on Smith Lake.

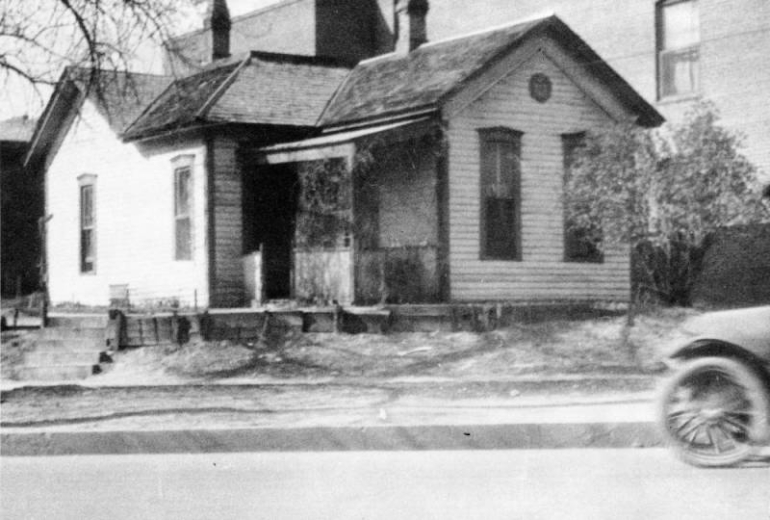

Journalist and poet Eugene Field's home was built around 1875 at 307 West Colfax, where he lived from 1881 to 1883, when he was The Denver Tribune's managing editor. After Field moved to Chicago in 1883, the house fell into disrepair. In 1927, Margaret "Molly" Brown campaigned to preserve the house from demolition. She raised funds to buy the house, gave it to the city, and stipulated it be moved to a park as a memorial to the beloved "Children's Poet." From 1930 to 1970, the house, now at 715 South Franklin Street, was Denver Public Library's smallest branch. The Park People, sponsors of Denver Digs Trees, maintain the house as their office. Founded by Mayor William McNichols, and Parks Manager Joe Ciancio, Jr., The Park People raise private funds for Denver's open spaces.

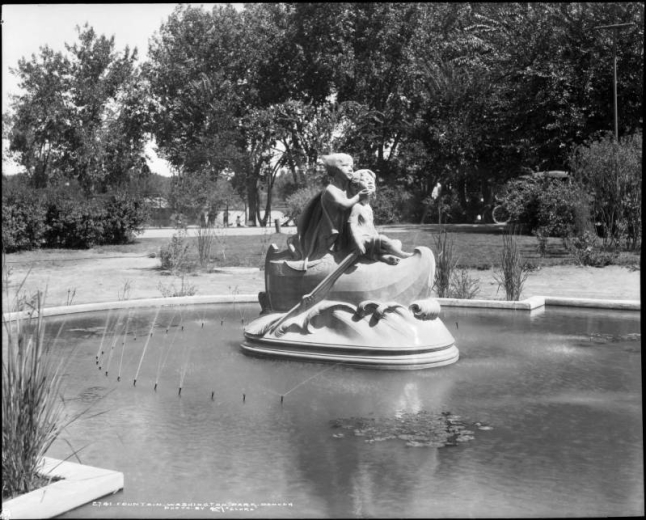

Sculptor Mabel Landrum Torrey's marble interpretation of Field's best-known poem, "Wynken, Blynken, and Nod," is north of the house. Mayor Robert Speer commissioned the statue, funded in 1919 by attorney Frank Woodward with ten $1,000 Liberty Bonds. The daughter of Sterling (Colorado) Judge John Landrum, Torrey was married to noted Abraham Lincoln sculptor Fred Martin Torrey. A 1938 bronze casting of the statue is in Wellsboro, Pennsylvania.

The Denver Public Library has many books and manuscript items by and pertaining to Eugene Field.

The origin of Washington Park community Church predates the creation of Washington Park. In the 1890s, the sparsely settled area was known as Myrtle Hill. In 1892, Myrtle Hill residents met at Frank and Carrie Bailey's home on the southwest corner of Kentucky Avenue and South Franklin Street to found a church. The Baileys were subdivision developers who grew alfalfa on adjoining fields and owned a nursery on the 900 block of South High Street. Myrtle Hill neighbors decided to seek help from Reverend John Collins, a Methodist missionary. Collins worked with the group as funds grew for a modest building. In February 1893, Ellen and Lydia Lort started a Sunday school for neighborhood children in their home at 725 South High Street (Lydia Lort later wrote an East Washington Park history, A Church Bell Rings in Denver). The Baileys donated five lots on the southwest corner of South High Street and Tennessee Avenue, and Myrtle Hill Methodist Church was completed in September 1893.

In 1911, the church was officially renamed Washington Park Methodist Episcopal Church. By this time, Washington Park was almost fully landscaped and the area's residential construction was underway. The 1893 church building was not adequate for a growing congregation and a new building was needed. This six-lot site was donated by John Evans II, grandson of Territorial Governor John Evans and son of William G. Evans. William G. Evans was an owner of the Denver Tramway Company and a heavy investor in Denver real estate, partnering at times with Frank Bailey. Construction began for the new building in 1917. The cornerstone was laid by University of Denver Chancellor Henry Buchtel, and in 1918, the church bell was ceremoniously moved to the tower. The church dedication was on January 5, 1919.

Smith Lake lies in a natural depression that may have been a buffalo wallow. The depression became a lake in May 1867 when Smith's Ditch was completed. The ditch flowed nearby bringing much-needed water from the South Platte River to Denver. Smith Lake, originally Smith's Lake, was envisioned as a reservoir associated with the new ditch. In May 1875, Denver acquired a ninety-nine-year lease on Smith Lake. For early settlers, the lake was an attractive feature on the treeless prairie. After the area became part of the Town of South Denver in 1886, the town attempted unsuccessfully to create a park that included the lake. Smith Lake was used in the 1890s for ice production. Without reporting the location, an 1892 Rocky Mountain News article declared three ice houses "immense in proportion and capacity" near completion for the lessee of Smith Lake.

In 1897, three years after the area was annexed by Denver, Mayor Thomas McMurray initiated condemnation proceedings on land south of Smith Lake to create a park that incorporated the lake. By 1904, Washington Park reached its present size through additional land purchases. In 1905, the pump house (the small building with the red tile roof on the south shore) was built to help irrigate the newly planted park.

In 1911, Smith Lake's north shore provided Denver with its first bathing beach. On opening day, 200 swimmers appeared. The new bathhouse dispensed swimming suits - knee-length shirts and capped sleeves for women - but only 180 were in stock. Rompers and overalls were deemed proper alternative swimming costumes. Men floated in small boats to mark the swimming boundary on that first day. During the first couple of years, the men's and women's swimming areas were separated by a rope.

Use of Smith Lake for swimming was free, but everyone was not free to use it. Only Denver's white population used the swimming beach, the lake, and the facilities. In 1913, Denver citizens of Japanese descent were officially barred. Segregation affecting other minorities was in place unofficially.

One integration attempt occurred in 1932, when 150 African-Americans arrived at the beach with the intention of swimming. Admitting there was no law against these citizens using the lake, Parks Manager Walter Lowry and Police Chief Albert Clark urged protesters to leave before trouble broke out. The protesters instead demanded police protection. The African Americans entered the water, but soon white swimmers who had left the beach returned with clubs and stones. Fighting ensued for over one-half hour and spread to ten blocks on the east side of the park. A crowd gathered to watch the spectacle. Police arrested seventeen people - ten African-Americans and seven whites who had encouraged the protesters to assert their rights. There was no further violence or demonstration. The story that came out about the incident blamed Communist propaganda. Newspapers reported that white Communist sympathizers drove the protesters to Washington Park and alerted the police that the protesters planned to swim in Smith Lake. Even Denver Mayor George Begole stated that the protesters were the victims of vicious Communist propaganda.

The free Smith Lake swimming beach was part of Denver life until the beach closed in 1957. South High School swim teams used the lake for practice sessions. Pollution, the polio scare, and the difficulty of chlorinating the lake were the reasons for the closure. In 1971, the construction of the recreation center gave Washington Park an indoor pool. The lake continues as a popular fishing and boating venue.

In 1920, this residence was featured in Denver Municipal Facts, a Denver City Beautiful-era publication. The first owner James Causey was a partner in Sweet, Causey, Foster & Company, an investment firm. Causey's lifetime interests included improving the workings of government. A personal friend of Central American leaders, Causey worked for better understanding between Central American countries, Mexico, and the United States. He also endowed the University of Denver Social Sciences Foundation. During World War I, Causey worked for the YMCA in France.

The 1923 funeral service for Causey's wife, Mary, was held in this house. In attendance were the governor of Colorado, other dignitaries, friends, and the Washington Park Community Church choir. In 1929, James Causey married Margaret Writer, daughter of Colorado Fuel & Iron Company vice-president Jasper Writer. Causy started a chain of furniture stores, but lost his growing financial empire when the stock market crashed the same year.

The new owners in 1929 were William C. and Orian Sterne. Indiana-born Sterne graduated from Harvard and traveled Europe before settling in Colorado in 1895 for his health. Sterne found financial success in the public utilities business. He helped guide the early days of the Child Research Council, the Civic Symphony, and the Denver Art Museum. He was a Rotarian, a Mason, and a Cactus Club member. He served twelve years on the Denver School Board. Sterne was one of Colorado's earliest football referees, officiating at the University of Colorado and other schools' games. He was once kidnapped in fun and left tied up in the Garden of the Gods after fans disliked his calls at a Colorado College game. Sterne died of a heart attack in this residence in 1948. The house next door at 1196 South Franklin was built in 1999 on the grounds of Causey-Sterne House.

Causey-Sterne House - 1190 South Franklin Street, built 1913 for $14,000 by architects Willis A. Marean and Albert J. Norton

South High School traces its origin in 1893 to two rooms in the old Grant School building at Colorado Avenue and South Pearl Street. Junior and senior high school students shared space until bond issues granted Denver Public Schools (DPS) a vigorous building program in the 1920s. John Cory was appointed principal in 1919. He lived nearby and established a reputation as a democratic principal, respected and well-liked by the students and community.

South High School is built on 172 acres of land that once belonged to Colorado & Southern Railroad. One DPS goal was to locate new high schools, South, East, and West, near parks and boulevards, and the location for South High School was considered one of the most beautiful in the city. South High School's cornerstone was laid on October 31, 1923. The first classes were held in January 1926.

Architects William E. and Arthur A. Fisher were inspired by two buildings in creating their design: Milan's St. Ambroggio's Church and, for the clock tower, Rome's Santa Maria in Cosmedin Church. Sculptor Robert Garrison created South's symbolic protector, the gargoyle perched high above the entry. Elaborate terra cotta embellishments contrast with red brick walls, and red tile roofs cover the main building and the clock tower. The entry's arch is flanked by striped columns supporting creatures representing faculty members. Above the main entry is a loggia with five arches. In 1935, Allen True painted murals in the main entrance hall. Over the years, interior space has been reorganized. The southwest wing was built in 1964, and a new gymnasium was built in 1989.

This building is the 1928 addition to Washington Park [Elementary] School, a 1906 five-classroom building that stood on this site for almost 100 years. Additions in 1915, 1916, and 1922 also kept pace with the growing population, but this 1928 addition was the largest and most elaborate, providing seven classrooms and an auditorium. Architect Harry J. Manning designed other City Beautiful Movement school buildings, including Fairmount Elementary School, 520 West 3rd Avenue, and Cathedral High School, 18th and Grant Street. He was known for his exuberant use of terra cotta on public buildings and grand residences. One of his residential designs is the 1931 Verner Zevola Reed house, at 537 Circle Drive.

The school was first located one block north on the southwest corner of Tennessee Avenue and South Race Street. Named Myrtle Hill Scholl, it was built in 1893. School principal George McMeen and Etta Bradshaw were the first teachers in the two-room building. The school became part of the Denver Public Schools (School District #1) on December 1, 1902, when Governor James Orman signed the Rush Amendment creating the City and County of Denver. In 1903, School District #1 gained legal title to Myrtle Hill School. Myrtle Hill remained the school's name when it moved to this site in 1906, and McMeen remained principal through 1917. On September 1, 1923, the name changed to Washington Park School (another Washington School was part of Denver Public Schools until the early 1920s). Washington Park School closed in 1982. The site was purchased by Denver Academy, a private school founded in 1972. Denver Academy built large additions and remained in operation at this location until 2000. After brief ownership by Denver International School, the site was under redevelopment in 2007 by new owners.

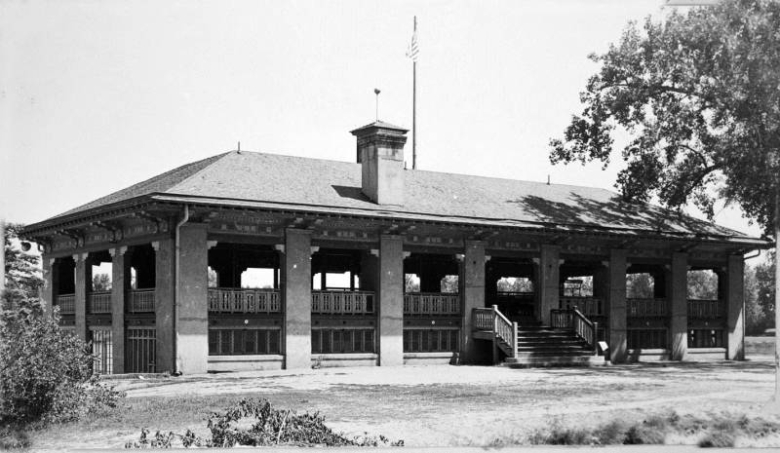

Colorado historian Thomas J. Noel describes the building as a mix of Prairie, Italianate, and Arts and Crafts styles. Jules J. B. Benedict designed this civic building only four years after moving his practice from New York City to Denver. Best known for his Beaux Arts designs, Benedict was a stickler for detail and demanded perfection from craftsmen and construction workers. He dressed meticulously with the help of his valet, carried a cane, and wore spats.

The Boathouse and Pavilion on Smith Lake's south shore is a uniquely designed two-story structure. The main level is designed for boat storage while the upper level provides an open pavilion suitable for large gatherings. In winter, the boathouse gave warm shelter to ice skaters. Lakeside doors provided access to straw-covered floors, and hot chocolate was provided. The pavilion's clever gutter system allows easy cleaning. Water sprayed across the floor collects in gutters and funnels through the scuppers spaced around the building's perimeter.

By the 1980s, the building was in dire need of restoration. Anthony Pellecchia Associates was retained for a complete renovation. One of the firm's architects, Jennifer Moulton, would later become head of Community Planning and Development for Denver under Mayor Wellington Webb. Pellecchia's career started in the Philadelphia firm of Murphy Levy Wurman in 1965. He established his Denver firm in 1984 and moved to Seattle in the 1990s.

Paddleboats, kayaks, and canoes can be rented near the Boathouse during fair weather for use on sixteen-acre Smith Lake. Pavilion space is often rented for private events and occasionally is used for art shows. In the evenings, the Boathouse provides a popular Denver sight with the lake reflecting the glow of original electric lights shining from beneath the eaves.

The fire station at the corner of Virginia Avenue and South Franklin Street was built in 1924. Four firefighters are always on duty here with one engine and one command car in readiness. Arthur Siegried & Associates also designed Denver's Fire Stations Nos. 7 and 13. A new building replaced the old one in 1974.

Named after a lake and William Wordsworth's home village in England's Lake District, manmade Grasmere Lake attracts a variety of birds. Dr. William Bergtold, a noted Denver physician, documented Denver bird populations. His 1918 book Birds of Denver includes numerous early sightings in Washington Park.

Grasmere Lake, at 1000-1299 South Washington Park, was originally called South Lake. During the 1990s, there were reportedly sightings of a crocodile in the lake, but this was never verified. The lake was drained and refurbished in the late 1990s.

Opening day for the swimming beach in 1911 was also opening day for the concrete bathhouse. The 1911 west wing held the men's dressing room. On opening day, the women were provided a large tent. The women's wing was built in 1912. Use of the swimming beach remained free, but a small charge was levied for suits, lockers, soap, and towels. The bathhouse waiting room, with a fireplace at each end, was used as a warming hut for ice skaters in winter. Though never built, an indoor swimming pool wing was included in the 1911 bathhouse plans. Two piers were built in 1914. A third pier featuring a high diving board on a wooden tower was built in the 1930s.

Two recently-discovered drawings document city engineer Frederick W. Ameter and architect James B. Hyder as the bathhouse architects. Ameter also designed Denver's Montview Boulevard and Richthofen Parkway. Hyder also designed St. James Church, 1615 Ogden Street. The bathhouse builder was Charles J. Dunn. Born in 1866 in New York to Irish-American parents, he was a successful Denver contractor for over thirty years.

Root Rosenman Architects completed a sensitive bathhouse renovation in the 1990s. The firm's mission was to preserve the bathhouse, while adapting it for use by Volunteers for Outdoor Colorado (VOC), a nonprofit organization. Other designs by Robert Rood and Seth Rosenman include the Young Americans Bank in Cherry Creek and Dwire Hall, University of Colorado, Colorado Springs.

Founded in 1984, VOC's mission is to motivate and enable citizens to be proactive stewards of Colorado's public lands. Dos Chappell, VOC's founder and executive director for fifteen years, died in 1999. In 2000, Denver City Council named the bathhouse in his honor.

This Craftsman-style building, at the north end of Smith Lake, was constructed in 1911-12 at a cost of $10,000.

The Washington Park Lawn Bowling Club, coed from its inception, created its regulation 120-foot square green and built the octagonal Club House. Members played the age-old game in traditional white clothing with black balls, unique for having a "bias" on one side. Adam Kohankie, the park's second superintendent, and John Saunders, Denver's first lawn bowling instructor, tended the green until the mid-1930s. In 1986, the Denver Croquet Club moved from City Park to share the green, using a regulation 84-by-105-foot area for competitions. The clubs maintain the greens. Memberships are open to the public and private groups may use the facility. The green was originally created in 1920, and the clubhouse followed in 1925.

Bibliography

The information in this exhibit is pulled primarily from a Historic Denver Guide, Washington Park Neighborhood. Historic Denver, Inc. has published a number of guides for the various historic districts and building styles in Denver. These guides can be purchased at Historic Denver. The guide for Washington Park includes much more information and tours of the area. More information is available on the Historic Denver and Denver Public Library's Western History website.

Search our database for images of Washington Park, or explore books and manuscripts using the bibliography link below.