~Written by Angelina Scolio, University of Denver Internship Student ~

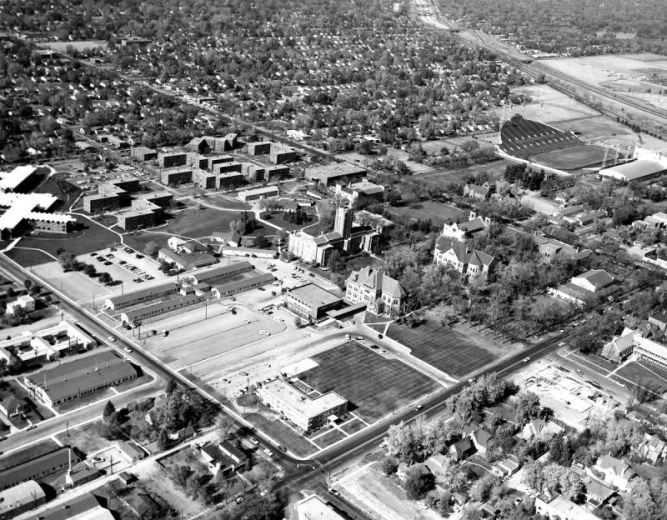

This center of cultural activity is the home of the University of Denver. The area features some of south Denver's finest architecture. Surrounding the university are mostly one-story single-family homes with spacious lawns. The area continues to be a largely Anglo community with the shopping convenience of quaint commercial districts interspersed with long tree-lined residential streets.

Clark Secrest, writing in Colorado Heritage magazine in 1992, pointed out that the short-lived town of South Denver had its own railway and its own university, but almost no saloons. The Town Hall was located at 1520 S. Grant St. in the former home of Mayor James Fleming who served three terms. The original boundaries of South Denver went from Colorado Boulevard to the east, Pecos Street to the west, Yale Avenue to the north, and Alameda Avenue to the south.

South Denver formally existed for only eight years, from 1886 to 1894, but played a crucial role in the growth and development of University Park, and vice versa.

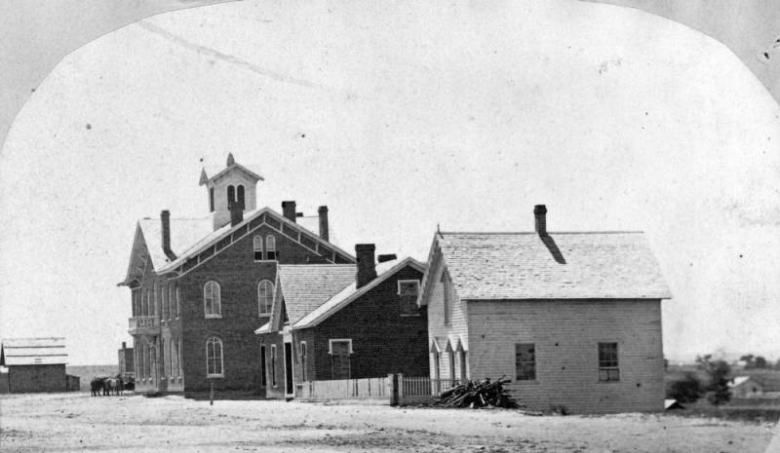

Colorado Seminary, as the University of Denver was originally known, was founded in 1864 by John Evans and a group of prominent Denver citizens. Evans had previously founded Northwestern University in Chicago and wanted to create a college in Denver so future generations would not have to travel back east for higher education. Colorado Seminary occupied a single building at 14th and Arapahoe streets in Denver, approximately where the parking garage for the Denver Center for the Performing Arts now stands.

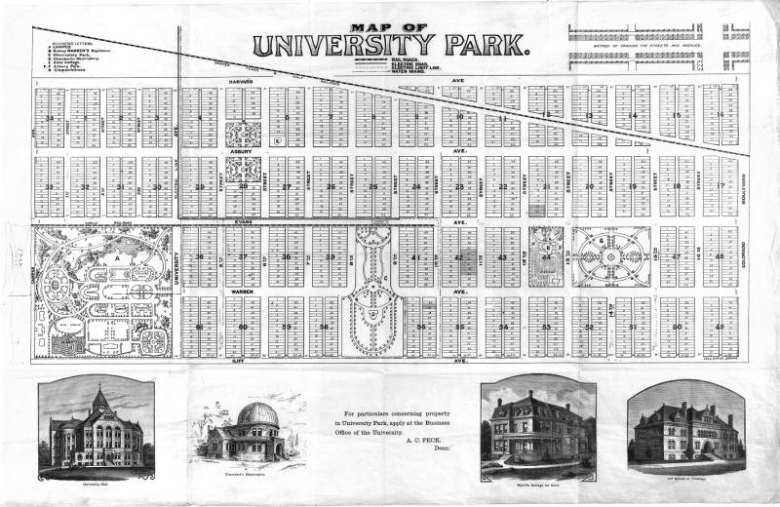

In 1880 the school added the name University of Denver as the degree granting institution. It would own all property and the University would grant degrees. By the 1880s the Seminary Building was land locked, making expansion difficult. Downtown Denver was also increasingly becoming home to a large number of saloons and brothels, just the type of institutions the good Methodist founders wanted to avoid. They wanted to create a utopian educational colony, a “university park.” Evans already had some experience in this area, having helped develop Evanston, Illinois, the suburb of Chicago where his Northwestern University was located. Deciding to vacate the downtown location for a more pastoral setting, the Board of Trustees in 1886 considered several offers of land, including parcels in Barnum’s Addition and in the Swansea area.

The offer that was accepted came from a group of farmers headed by Rufus “Potato” Clark who promised 150 acres three miles southeast of the city limits in what was then Arapahoe County.

Clark had conditions to go with his offer, such as the planting of trees and the laying out of a street grid. He also demanded that no alcohol ever be made or sold in the area. Legend has it that Clark was a reformed alcoholic who had been saved at a tent revival meeting. Today you will still find some home mortgages in south Denver with old covenants against producing or selling alcohol on the premises. In areas outside of Clark’s original gift, the town of South Denver placed a $3,500 annual saloon license fee, high enough to keep out most of these types of establishments. Within a short time other gifts of cash or outright gifts of neighboring land swelled the University’s holdings to nearly 500 acres in the area.

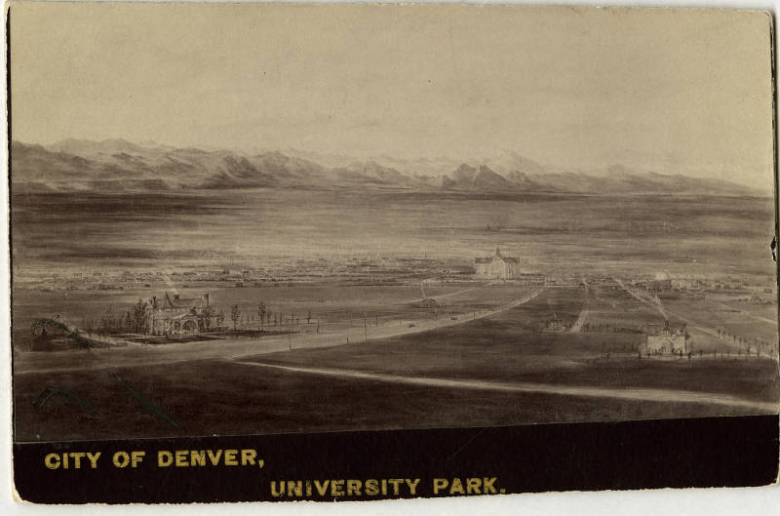

Methodist Bishop Henry White Warren and his wife Elizabeth demonstrated their support by purchasing land east of the University and in 1887 began construction on a home that came to be known as Gray Gables. Clark’s land offered a stunning view of fifty miles of Front Range Mountains away from the smoke and pollution of Denver. Charles Haines, an early resident, recalled in an interview when he was 102 years old that jackrabbits and coyotes outnumbered people for a number of years. Over the next few years the University sold lots in the area to raise revenue.

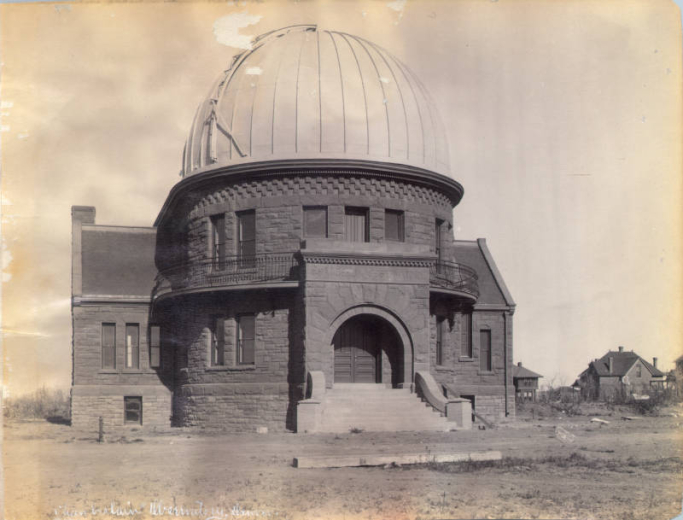

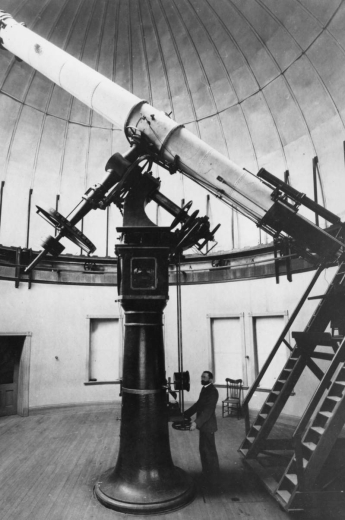

In 1887 the Denver Circle Railroad extended a line into University Park. The next year ground was broken in University Park for Chamberlin Observatory. Real estate promoter and amateur stargazer H.B. Chamberlain had given the funds to build the Observatory. One advantage of building an observatory in University Park was the lack of urban lighting, which interferes with stargazing.

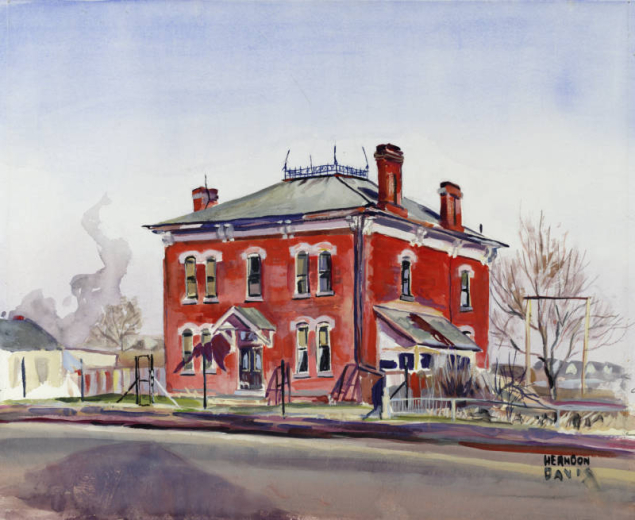

Evans erected an office building at the corner of what is now Evans and S. Milwaukee which housed the first Methodist Church in the area. The building still stands and is today a real estate office.

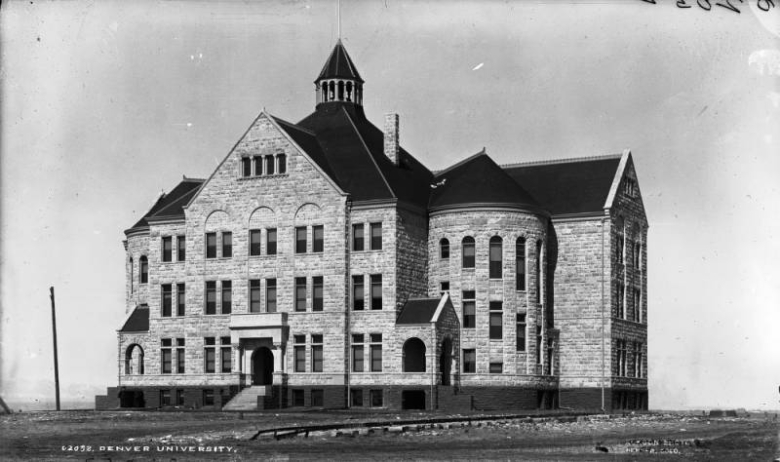

In 1890 ground was broken for University Hall, and in the fall of 1892 the school officially relocated to University Park. Church services would now be held in University Hall, which also housed all of the classrooms, administrative offices, the library, and the gymnasium.

Though South Denver had several hundred residents by the mid 1890s, only a dozen or so residents were actually living in University Park. Despite these small numbers the park already had telephone service, a post office, graded roads, and water from a well at Milwaukee and Warren. It would be more than ten years before electricity was installed throughout the Community. South Denver was still largely farmland, primarily growing alfalfa, corn, beets, apples and cherries. The town of South Denver ceased to exist when voters approved annexation by the city of Denver, primarily for financial reasons. Though the residents of South Denver wanted to maintain their independence from the big city, the Panic of 1893 had made a negative impact on real estate values. Taxes would be cheaper and more city services provided by annexation. South Denver was not alone. Within ten years Denver had annexed Park Hill, Highlands, Barnum, Colfax, Globeville, Montclair, and Valverde.

Today’s University Park and South Denver are a vibrant part of the metropolitan area with beautiful homes and a tremendous variety of shopping and restaurants. The population has expanded to include many individuals not at all associated with the University of Denver. These are mostly younger upper middle class white-collar professionals. Some things never change though. Liquor laws were relaxed after World War II and it is now not so difficult to find a drink in south Denver, but neighbors still debate the granting of new liquor license applications, especially around the DU area.

The trolley tracks, torn out in the forties when buses became the norm, are being replaced again by light rail. Light rail service is welcomed because traffic and parking have become more serious issues as older retired people move out to assisted living facilities and their homes are sold to landlords for rental properties. Where the former occupants may have had one or two vehicles, the new occupants may have five or six. Pop-tops and scrape offs are now hotly debated topics in University Park. Location is everything, and because University Park is so popular a location (being roughly half way between downtown and the Tech Center) investors are willing to enlarge smaller older homes in the area. The term “architectural mooning” has come to describe what occurs when a home is expanded dramatically next to a much smaller one.

Chamberlin’s 20-inch refractor telescope is still the largest of its type in the rocky mountain region and still attracts scores of viewers to Observatory Park. Though much of the breathtaking view of the front range is now gone, portions of it can still be seen here and there from higher buildings on the DU campus and other nearby areas such as Harvard Gulch Park.

by Steve Fisher

Curator of Special Collections,

University of Denver Penrose Library

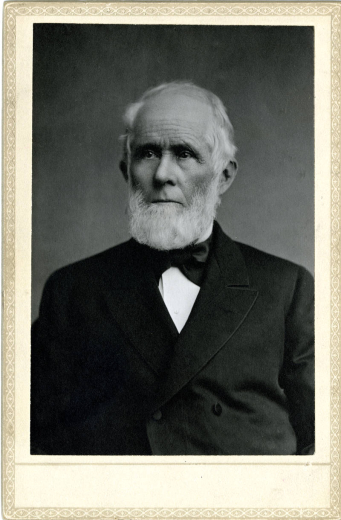

Rufus “Potato” Clark was one of the original settlers of the Highlands Ranch area. Clark became an active member in the political and philanthropic world of early Denver.

Rufus “Potato” Clark arrived in Denver in 1859. He sold vegetables to miners and is believed to have earned $30,000 in one year from potatoes alone. Because he made his fortune selling potatoes, Clark became known as the “Potato King of Colorado.” Clark was an active member in the political and philanthropic world of early Denver. He served as a member of the Territorial Legislature and assisted the Salvation Army in acquiring a building for their headquarters. He sent most of his potato crop to Chicago after the great fire, and built a college in Africa. He is also rumored to have owned 160 acres of what is now the Highlands Ranch Golf Club.

However, Clark is more widely known for heading the movement which culminated with the donation of 150 acres of land located three miles southeast of Denver, in then Arapahoe County. This land would become the foundation for the University of Denver. This new land not only secured an escape from the moral and environmental pollution of Denver, but afforded the University with a spectacular view of the Front Range.

With his donation came a few conditions on how the land was to be developed. Clark required the planting of trees, laying out a street grid, and that alcohol would never be made or sold in the area. Although the surrounding areas allowed for the distribution of alcohol, a $3,500 saloon license fee was established to discourage establishments from selling alcohol. This discouragement of the use of alcohol is the source of some of the old covenants against the creation or distribution of alcohol for homes within the area today. Clark passed away in 1911.

Herbert Alonzo Howe was an internationally known astronomer and mathematician as well as a Professor of Astronomy and Applied Mathematics at the University of Denver from 1880 to 1925. Howe was influential in the early days of the University of Denver by holding many leadership positions within the institution. Some of his many roles include: Dean of the College of Arts and Sciences from 1892 to 1926, Director of the Chamberlin Observatory from 1892 to 1926, and Acting Chancellor at the University before 1900.

Howe was also instrumental in building the Chamberlin Observatory and the installation of the telescope there. In 1883 he began raising funds for a roof-topped observatory and in 1888 construction began. With the help of benefactors such as Humphrey Chamberlin, after whom the structure would later be named, completion occurred in 1891 making it the first official University structure. Three years later Howe personally carried a 20-inch telescope lens with him on the train from Massachusetts, making it one of the largest in the world.

Since Howe’s death in 1926, the Chamberlin Observatory has had a number of distinguished scholars who have overseen and advanced the educational functions and reputation of the institution.

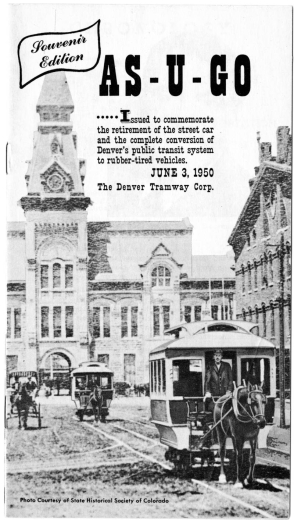

Transportation, or specifically rail transportation was, and still is, an important component of the University Park neighborhood. Being quite distant from central Denver, community members needed speedy access to downtown.

Horse cars began service in 1871. Early in 1885, the Denver Electric and Cable Railway Company began a series of experiments using an electric trolley developed by Professor Sidney Short, of the University of Denver. In 1887 the Denver Circle Railroad extended a line into University Park. New electric street railways, also known as streetcars or trolleys, enabled Denver to grow outward into the prairies. In 1889, members of the Denver Tramway Company incorporated the South Denver Cable Railway Company in order to extend the Tramway's Broadway cable line through South Denver. With the extension of the Denver Tramway Company’s trolley car line south along Pearl Street from Alameda to Evans and east to the University of Denver, the surrounding neighborhoods, including University Park, began to boom. Several other Denver neighborhoods, including East Washington Park, also received their own streetcar service in 1889, when the University Park Railway and Electric Line built through the area. The line aimed to connect the suburb of University Park, east of the University of Denver, with the Denver trolley line at East Alameda Avenue and South Broadway. The line was constructed from University Park northward. Because of this line (known as the number 8 line in later years) and since they were often piloted by students of the University of Denver, the University quickly became known as “Tramway Tech” and the neighborhood building boom continued.

Streetcar operation eventually ceased in 1950 due to low rider ship brought about by increased automobile ownership and use, but the tramway continued to operate conventional buses on the line and continued to use the Tramway name.

In 1974 the Regional Transportation District (RTD), a cooperative government transportation district, assumed operations of the system. University Park, as well as the entire Denver region, joined the new renaissance of streetcars, now called Light Rail, which began to occur in the U.S. The opening of the University of Denver light-rail station in the University Park neighborhood in late 2006 brought back the rails that were torn up in the 1940s and 50s, and gives the neighborhood the improved mobility and quick access to downtown as well as the entire Denver region.

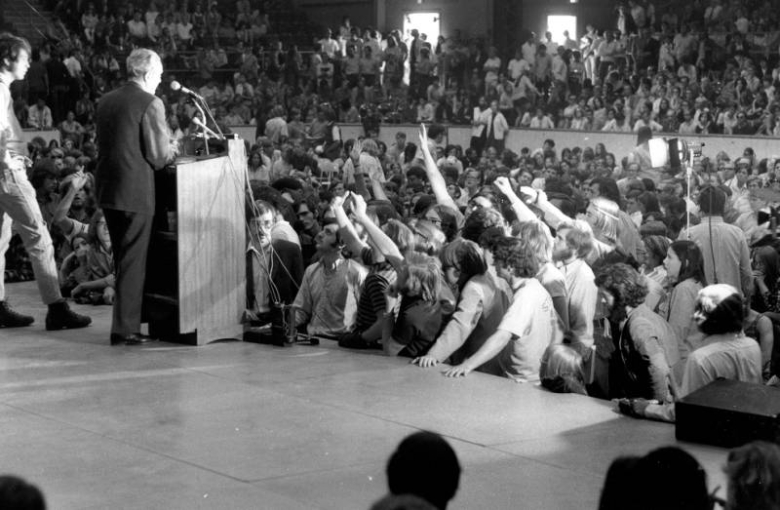

Spring of 1970 was a tense time across the United States, Denver being no exception. In May 1970, students at the University of Denver organized protests, fueled by elevation of the war in Vietnam and the shootings at Kent State.

On May 6th students rallied, formed picket lines and boycotted classes. Within hours the students, emboldened by their growing fervor and numbers, marched on Chancellor Maurice Mitchell’s office making a series of demands related to national as well as local (campus-wide) issues. However, his rebuff of the student’s protests only served to escalate their activities.

On May 8th the University acquiesced to a campus wide convocation, aimed at quelling the protests. However, students remained frustrated and decided to take their protest to Carnegie Lawn (now the site of the Penrose Library). They began building what came to be known as “Woodstock West,” a series of tents and crudely made shelters that formed an instant community for the discontented. In a matter of days the temporary shelters housed anywhere from hundreds to thousands of people at a time (still only a small percentage of the entire student population) and stretched across Evans Boulevard.

By May 10th, Woodstock West seemed to grow beyond the student population, and University officials decided to call in the Denver police. The next day 200 policemen and 40 state troopers arrived on the scene, made arrests and dismantled the shelters. However, the protestors persisted and a second encampment, Woodstock West II, was resurrected from the remains of the first.

On May 13th, the Chancellor finally called in the National Guard. By this time most of the temporary shelters had been abandoned, protestors disbursed and students returned to class. The campus continued to be closely monitored by Denver police until the 18th of May. Thus ended seven days of turmoil that brought national and international affairs closer to home, right to our backyard.

In 1986 a 14-year-old Boy Scout, named Barry Matchett, elected to earn an Eagle Scout badge by working on an oral history project for the University Park neighborhood. Barry collected fifty oral histories on cassette tapes from some of the older residents of the area. The subjects of these tapes range from memories of community celebrations to businesses long since gone. Upon the completion of Barry’s project his tapes were donated to the University of Denver Archives to be made available to later researchers. Learn more about this collection.

Oral History Interview with Andrew Gassman

Oral History Interview with Carolyn Etter

Oral History Interview with Chuck and Dorothy Haines

Oral History Interview with Frances Hayes

Oral History Interview with Helen Driscoll

Oral History Interview with Jean Blackledge

Oral History Interview with Jean Emery

Oral History Interview with John Ivey

Oral History Interview with Juanita Johnson

Oral History Interview with Kathleen Babcock

Oral History Interview with Loretta Eitelgeorge

Oral History Interview with Marjorie and Marion Cutler

Oral History Interview with Mary Coen

Oral History Interview with Mary Engle

Oral History Interview with Mr. and Mrs. Dorcas

Oral History Interview with Mr. and Mrs. Farnsworth

Oral History Interview with Mr. and Mrs. Max Grassfield

Oral History Interview with Mr. James Hurlbut

Oral History Interview with Mr. Sam Huddleston

Oral History Interview with Mrs. Ruth Geyer

Oral History Interview with Ralph Atkinson