In what is known as one of Denver’s most-up-and-coming places to live, Sloan’s Lake Neighborhood possesses choice sunsets, recreational activities, restaurants, modern housing, and a swath of new development. The boundaries are 29th Avenue to the North, 17th Avenue to the South, Federal Boulevard to East, and Sheridan Boulevard to the West. With Denver’s second largest park and the city’s largest body of water, the neighborhood has been a place of interest for Denverites since the lake’s miraculous origin in 1861. Although many of its historic places are no longer standing, their influence is still present in the Sloan’s Lake Neighborhood legacy.

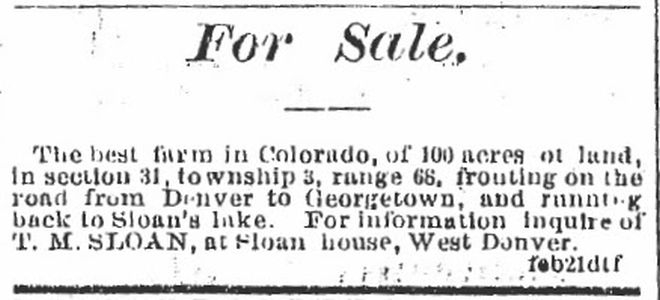

According to legend, in 1861, Thomas M. Sloan tapped into a water aquifer while digging a well to irrigate his farmland in what is now considered West Denver. Overnight, the lake spread to a whopping 200 acres and soon attracted onlookers to confirm rumors of a new body of water, graced with monikers such as “Sloan’s Leak,” “Sloan Lake,” and “Sloan’s Lake,” a name that would continue to be debated over a century later. The farm and an ice house on the lakeshore soon became prosperous sources of income for the Sloan family. Activities such as boating, swimming, and ice skating made Sloan’s Lake a popular recreational attraction in Denver. In 1872, Thomas M. Sloan sold his property after placing an advertisement in the Rocky Mountain News for the sale of “the best farm in Colorado.”

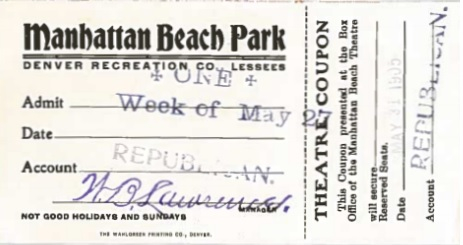

Manhattan Beach was one of Denver’s first amusement parks and was located on the North shore of Sloan’s Lake. When the park opened its doors in 1891, it was considered the largest amusement park west of the Mississippi. The park was the vision of German-born Adam Graff, an ambitious immigrant who was an ice cutter at Sloan’s Lake. With funding support from brothers Robert and Ernest Steinke, they were able to open the park while continuing to add newer attractions such as a roller coaster, a dance hall, a zoo, a skating rink, a theater, and more. The beauty of the park burgeoned as thousands of trees, shrubs, and potted palms were planted in the gardens and picnic grounds. A total of 10,000 visitors traveled from all around Colorado by way of horse, buggy, and streetcar for the grand opening.

Manhattan Beach lured patrons not only with its beauty, but also with its growing variety of attractions, performances, and athletic events held at the park. A pleasure barge named “City of Denver” was a Denverite favorite for its gentle cruises in the afternoon and late evenings. Circus acts, live bands, gypsy groups, baseball games, and boxing matches were all attractions that kept visitors returning. People enjoyed the view of ascending hot air balloons while acrobats were shot out of cannons. New animals such as camels, tigers, lions, elephants, and various Colorado wildlife were continuously added to the zoo within the park. There was even a Cinderella coach hauled by a pair of ostriches!

The park’s popularity was short-lived as it suffered from a series of unfortunate events. A horrible accident occurred when a child was fatally injured riding the park’s circus elephant, Roger. An ascending hot air balloon frightened the animal, causing several children to fall from his back. As the animal broke from his trainer’s reins, he trampled a boy to death. Roger was previously known to be gentle and never displayed behaviors to cause concern. Nevertheless, Roger was destroyed soon after, and is believed to still be buried underneath the intersection of 20th and Depew.

On December 26, 1908, a mysterious fire burned the theater and observatory down to cinders. The momentum of the park’s success came to a halt soon after. When Graff sold Manhattan Beach to Albert Lewin, the park became known as Luna Park. Several new attractions were added in an attempt to revive the park’s popularity, such as a smaller theater, a ferris wheel, a carousel, and a new steamboat called “Frolic.” The vessel was to replace the pleasure barge “City of Denver,” which sank after a violent windstorm in 1892. Alas, interest in the park was never the same, and it was permanently shut down in 1914.

In 1874, the Grand View Hotel opened its doors with advertisements slated for guests, tourists and pleasure seekers. Located on Federal Boulevard and 17th Avenue, the Grand View Hotel sat on a hill with a view of the Platte River. The hotel was accessible from the city via streetcar and from Sloan’s Lake through a canal. Passengers were transported via the “City of Denver” boat between the park and hotel for 25 cents. After the “City of Denver” sank, the hotel’s novelty began to fade, and it would endure many changes thereafter. It was converted into an insane asylum until St. Luke’s Hospital would briefly take up residence in the building. The building was demolished soon after St. Luke’s relocated.

Named after the “Wonderworker Saint,” Saint Anthony’s Hospital was founded by the Sisters of St. Francis in the late 1880s. Funding for the building was provided by contributions given to the sisters from Denver railroad men and miners. Saint Anthony’s Hospital was built on the west side of Sloan’s Lake, on West 16th Street and Raleigh Street. The six-story structure was completed in 1893, with additional buildings added in the early 1910s. A gong was placed at the entrance for visiting doctors to announce their arrival to patients. The building housed an X-ray room, two operating rooms, 20 doctors, and 48 sisters. The sisters ran the hospital with 120 ward beds and 60 private beds. The Sloan’s Lake location was abandoned in 2013, when St. Anthony’s was relocated to West Alameda Avenue and South Union Boulevard.

Designed by Highlands natives Merrill and Burnham Hoyt, Lake Junior High School was built in 1926, and was referred to as “The Castle” for its English Tudor-esque features. Facing the snowy mountain range, the school is located on the East end of Sloan’s Lake, on 1820 Lowell Boulevard. Lake Junior would become the most distinctive structure in the area because of its Moorish architecture combined with ornamental lights and soaring features, giving the school a medieval appearance. Artist Walter Pesman designed the garden area with varieties of native and imported flowers before the building was erected. Lake Junior eventually became a middle school with an International Baccalaureate program in the Denver Public Schools.

Located at 17th Avenue and Sheridan Blvd, the Lakeshore Drive-in Theater was owned by Civic Theaters and was the sixth drive-in theater to open in Denver on July 6, 1951. The theater was designed by R.L. Cunningham and H.M. McLaren, and had an indoor capacity of 200 seats and 1000 cars. The screen was 80 feet wide and 60 feet high with a sound system specially designed by R.C.A., and it included heating for car spaces. A lighted walkway was placed in the center of the theater leading to a playground built to accommodate younger audience members. The theater was known to have a special feature of lighted speakers for each of the car spaces to guide moving vehicles. After many successful year-round seasons, a fire burned the screen down in 1963. With dwindling public interest in drive-in theaters, the Lakeshore Drive-in was brought down in order to make space for the Edgewater Marketplace in the 1980s.

So what do we call it: Sloan’s Leak, Sloan Lake, or Sloan’s Lake? This has been a dispute among locals, newer residents, and visitors for a long time. In 1993, the City of Denver installed official signs labeling the park as “Sloan Lake Park.” Long time local residents knew the park as “Sloan’s Lake” and in attempt to change the signs and relieve the confusion, they created a petition. Signatures of neighbors, natives, and local historians, along with historical documents, proved the park was in fact dubbed “Sloan’s Lake.” In 2002, the city complied and the signs were later modified with the correct name: Sloan’s Lake Park. Even so, the City of Denver officially uses Sloan Lake for the name of the neighborhood.

With the breadth of history that has taken place at Sloan’s Lake Park, there is a surviving magnetism that attracts local residents, picnickers and athletes. Is there something enticing in the water? Could it be the sunsets? Maybe it’s all of the activities taking place at the park? Perhaps it’s a combination of many factors that increasingly make Sloan’s Lake the attraction that it is. Whether people are attending festivals, exercising, or just taking an evening stroll, their presence contributes to an expanding allure of a remarkable neighborhood.