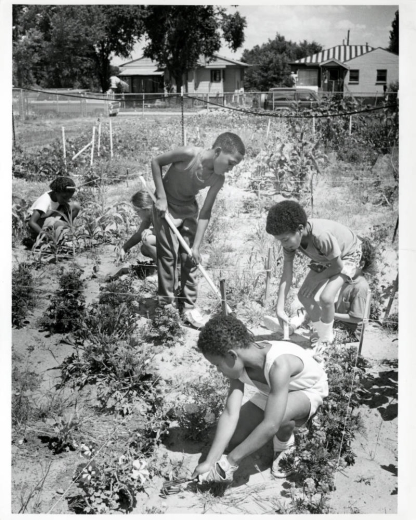

“The block of 47th and Logan had been cleared of trees and the large swamp filled in. The block was being used as a park. The men walked to work, the women baked bread and other items for the dinner table. Most families raised chickens, had a few pigs and a cow. Cattle could be seen along the lower part of the railroad tracks between 48th and 49th Avenues. Each family had a small garden in the back yard. In those days the Platte River came to the edge of the southern part of Washington Street. A person could walk along Washington Street and look down into the roaring river. There also were forests along the Platte River. Sand pits were in the area of 48th Sherman - Logan. The north-western part of Globeville was swamp land. Many of the homes were without foundations. Cement sidewalks were non-existing but the wooden ones were always clean. Even the wooden porches were washed down once a week. The government had the streets watered down to control the dust on the dirt roads.” - Globeville: Part of Colorado’s History by Larry Betz

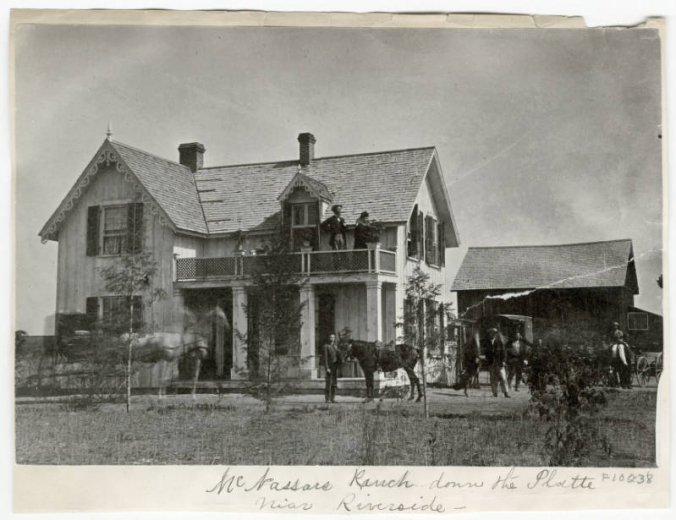

Like many communities on the periphery of early Denver, the place that became Globeville has a fascinating history. In earlier times, indigenous people likely came through on a seasonal basis without establishing permanent habitation. As Denver began to grow, the town that became Globeville grew too, with various farmers, ranchers, and traders settling. In the 1870s, as exploitation of Colorado’s mineral wealth grew drastically, so did the need for smelters with access to the railroad. Proximity to the railroad made the Globeville area ideal for such industry. This began with the establishment of the Argo Smelter in 1878, followed by the Holden Smelter in 1885.

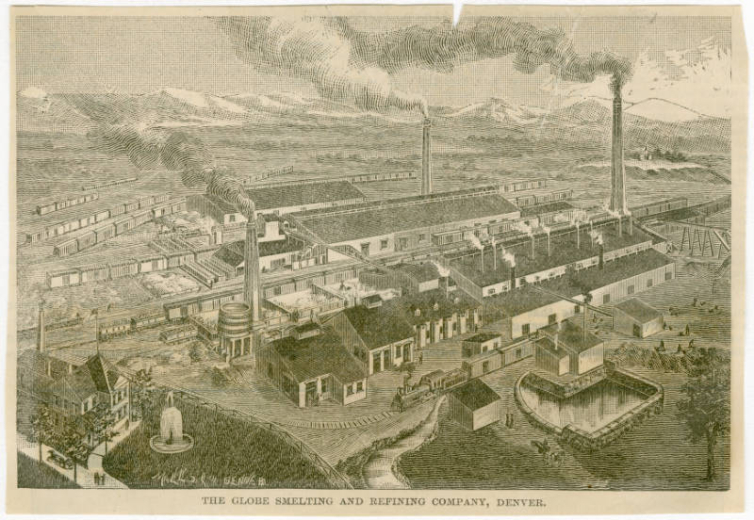

Globeville adopted the name Holdenville until that smelter was reorganized in 1889 as the Globe Smelter and Refining Company. In 1891, the town of Globeville was officially incorporated. By 1899, the smelter was sold again and was run by the American Refining and Smelting Company. Business was good and many immigrant laborers made their way to Globeville from Russia, Germany, Scandinavia, Poland, Slovenia, and many other parts of Eastern Europe.

While Globeville represented the immense diversity of American immigration, it was also incredibly isolated. Both the South Platte River and the railroads provided physical barriers between the city and nearby Denver. Globeville remained its own municipality until it officially joined Denver in 1903. Cars were not then prevalent, streetcars did not extend into Globeville until 1908, and most roads there remained unpaved into the 1920s. In this sequestered neighborhood, local and ethnically-centered churches, societies, and social clubs thrived.

On June 27, 1920, the Denver Post ran an obituary for one of the earliest settlers of the Denver area: one William Hanford Clarke, known affectionately as “Uncle Billy.” Clarke had been born near Cleveland, Ohio, in 1835. After working as a quarry boy in Council Bluffs, Iowa, in 1854 and then making a land claim near Fort Calhoun, Nebraska, he began to hear tales of gold trickling in from Colorado. In 1858, he joined a group of men making their way west via oxen train. He later recalled seeing little in the region besides Native Americans and buffalo.

Upon arriving in Denver, he reported seeing several wigwams and the scattered tents of white men. After a few months, he decided to try farming, found some land to squat on, and built the cabin where he would spend the rest of his days. In 1882, he married Mary Dornbosh. They had a daughter who eventually moved to Salida. Clarke would go on to become the mayor of Globeville subsequent to their incorporation in 1891. He was also a member of the school board and was involved in the continual effort to make improvements to the growing town. According to the census, Clarke and his cabin were still standing at 5041 Pearl Street in 1920.

This church is located at the southwest corner of East 47th Avenue and Logan Street. Like many churches of its time, it has Gothic Revival features, such as the pointed arch entrance and windows. There is also a square tower featured in the center of its facade. It was initially founded as the Byzantine Catholic Church by Carpatho-Russian immigrants in 1898. The first priest was Father Nicholas Seregely. He spoke no English and died of illness in 1903. At that point, the congregation decided to join the Russian Orthodox Church and installed the new priest, Father Vladimir Kalneff.

Under Kalneff’s leadership, improvements were made to the church and a hall was added beside the structure. The iron fence around the church was said to have been moved from Denver’s old Union Station. In the 1930s, the church became the Russian-Serbian Church and, in the 1960s, saw another name change to the Transfiguration of Christ Eastern Orthodox Church. Bishop Tikhon of Moscow, now a saint within the Orthodox Church, visited the Globeville church in 1904 and 1905. In 1905, he personally constructed the original altar table and deposited within it relics from his own patron saint, Tikhon of Zadonsk. To this day, you can still participate in the annual celebration of the food, music, and culture that this parish represents.

This Gothic Revival church stands at 517 East 46th Avenue and was built in 1902. It includes five arched stained glass windows, a conical tower, and Gothic elements such as the pointed arch openings. This is the oldest national Polish church in continuous operation in the western United States, and was added to the National Register of Historic Places in 1983. The early congregation included Poles, Croatians, and Slovenians. The first pastor was Reverend Theodore Jarszynske, who also served the community by offering English classes to Polish immigrants. During feast days, such as the Feast of Corpus Christi, large processions held by the church would move through the streets of Globeville with various ornamented altars displayed on the front porches of neighborhood homes.

Almost immediately after the construction of the aforementioned St. Joseph’s, the Croatian and Slovenian populations began to petition the Archdiocese of Denver for their own church. This church, built in the Romanesque Revival style, sits at the corner of 47th Avenue and Pearl Street. It features 50-foot-high paired towers and a large stained-glass window. Construction began in 1919 and a rectory was added in 1921. The Mission Revival-style church school, as well as an addition to the east side of the church, were constructed in 1928. The school operated until 1969 when costs became prohibitive to the local community. The church remains in operation today.

One important feature of the Garden Place Historic District (originally known as “The Waterhole”) is the Garden Place School. According to an interview with resident Lauren Summers, The Waterhole included sandpits that would fill with water and served as a swimming hole for children. The original structure was opened in 1882 at the corner of 44th and Lincoln, and served a small number of students. That structure was razed in 1902 and the current Renaissance Revival structure was finished in 1904. The school had a very close relationship with the German Congregational Church that sat across the street. From the earliest part of the 20th century, the school provided citizenship classes to local immigrants. Matthew Eagleton, the principal until 1920, even provided special classes for immigrant children to learn English prior to joining mainstream classes. He was greatly respected across the Globeville community throughout his tenure.

The park began in 1880 as a place for the families in the town of Argo to recreate. It was then purchased by local brewing magnate Philip Zang in 1885. Zang added amenities like theaters and dance pavilions, in a model not unlike Lakeside Amusement Park. The New Deal era of the 1930s brought the addition of a pool and changing rooms, and more upgrades were made in the early 21st century. To this day, the park remains a highlight of the community and a place for local families to gather and socialize.

“If you built a model-train layout, this is what you would do: You would have little houses next to each other, and they would have out-buildings, and sheds, and chicken coops, and summer kitchens; a mother-in-law apartment, the barns. And neat-as-a-pin yards—gardens, trees, bushes, flowers. There were seven or eight churches in Globeville. There were little groceries—there were a lot of barbershops. Shoe-repair stores, notions shops. And you could walk everywhere. It was safe to walk from 4552 Sherman to Argo Park.” Mary Lou Egan Oral History

Just as in the previous decades, neighborhood demographics continued to evolve. Following WWII, there were no longer large influxes from Eastern Europe, and Latinos and African Americans began to move into the area looking for jobs in the numerous local production industries. For a time, there continued to be the close-knit, somewhat isolated community that Globeville had always represented, but more challenges were soon on the horizon. By 1958, Interstate 25 (Valley Highway) was completed and cut across the western edge of the community. By 1964, Denver completed the construction of Interstate 70, which cut through the community's heart, taking 31 houses with it. I-70 also cut off the historic Garden Place District from the rest of Globeville. While the convergence of railroads and highways made the area attractive to industries such as smelters and meat-packing, the environmental impacts from pollution only compounded over time.

While the Omaha-Grant Smelter (on the current site of the Denver Coliseum) ceased operation in 1903, from 1944-1950 its facilities were used to incinerate trash in Denver. In the 1970s, residents complained to the Denver Planning Board about issues like animal rendering plants near their homes, waste-water facilities that regularly overflowed and backed up local sewers, and the fact that some streets and alleys remained unpaved.

The Globe Smelter, which granted the neighborhood its name, had been purchased by ASARCO in 1899 and continued to operate for another 107 years until it declared bankruptcy in 2006. Besides precious metals, the plant also produced the toxic elements lead, cadmium, and arsenic. In 1983, the State of Colorado sued ASARCO to investigate contamination liability. Residents of the area filed a class-action suit in 1991, and ASARCO eventually settled with an agreement to clean up toxic household yards and gardens. A 1988 Environmental Protection Agency investigation identified high levels of lead and arsenic in the soil. The EPA designated the area a Superfund site the following year. This led to additional soil mitigation efforts by the government. By 2002, the Agency for Toxic Substances and Disease Registry sent letters to 650 homes that had yards deemed so toxic they could cause cancer in residents. This agency also found that 9% of children between 7 months and 6 years of age showed dangerous levels of lead in their blood.

As recently as 2018, the 80216 zip code was ranked the most dangerous in the country. As the news source Denverite points out, that calculation is quite a bit more complicated than it sounds, but community activists continue to wrangle with the history of neglect by government and abuse by industry. 2018 also saw the start of the Central 70 Project, which will widen I-70 and change the viaduct into a highway that runs below ground level. This project has, again, sparked anger over the possibility of increased air pollution, groundwater contamination, and disruption of contaminated soil. The project is ongoing as of this writing in 2020.

While the diversity of faiths and ethnicities that characterized Globeville for generations was expansive, so were the myriad social clubs that were formed and eventually faded into history. There is a beautiful vignette of one such club in the Rocky Mountain News from December 31, 1987. John Popovich hadn’t had a drink of alcohol since the end of World War II, but he moved to Globeville in 1948 to take his father’s place running the Slovenian Home, a neighborhood bar where multiple generations of families would spend an evening. The club had been home to multiple Slavic social organizations and had weathered the neighborhood fractures brought on by the interstates and encroaching industries The night this news story was published was the last night the club would remain open. In the article, Popovich mused to the author that he might have a sip of champagne after 42 years without alcohol.

“It’ll be a terrible loss when this place closes,” said a man in a blue coat who identified himself only as Neil. “I’ve been coming here for 20 years and never seen a fight. The friendship in this place is something else. There’ll be a lot of people with tears in their eyes, and I'll probably be one of them.”

While many of the ethnic social clubs and traditional neighborhood bars have faded, the Globeville Recreation Center remains an important part of the community for children, families, and activists. It started in 1920 with a $2,500 building fund donation from William P. McPhee of the Denver Library Board. The Denver Real Estate Exchange was then able to raise the remaining funds needed. The Globeville Community House, as it was then known, opened in 1921.

The Globeville Community House has changed management many times, but has always stood at 4496 Grant Street. In 2012, the Birdseed Collective began operating out of the recreation center and, as of 2018, was awarded a city contract to operate the center itself. Birdseed Collective co-founder Anthony Garcia, Sr. started as a local graffiti artist and moved into the realms of canvas paintings and large-scale street art. After taking over management of the recreation center, the Collective expanded hours, started providing healthy food in a community that has become a food desert, and got kids and community members involved in art projects that beautify the community and encourage more private investment. As he stated in an interview given to 303 Magazine,

“We want to have this huge umbrella that covers it all,” Garcia said. “We have the magazine [1of1 Mag], we have the art gallery [Alto Gallery], we’re doing so much stuff with the city as far as the public art goes, we do the food programs and community groups.”

Globeville has long been defined by the struggles of its inhabitants, whether those be the hard life working a smelter in a company town or the strange tale of men pushed to live underground in the midst of the Depression. It’s often forgotten that the light shines on these struggles thanks to the legacy of local activism that endures in the community. Early immigrants to Globeville sought relief from poverty and oppression, worked together to find a place in a new country, and did what they could to make life a little easier for the next generation. Later residents organized and fought polluting industries that threatened the health and lives of their families. Today, community leaders continue to overcome the social and physical barriers that have long contributed to city neglect. The toil of this working-class community has benefited the greater Denver area for more than a century.