~Written by Ryan Bell, University of Denver Internship Student ~

Compared to other Denver neighborhoods, Fort Logan appears somewhat out of place. Perched on a plateau overlooking much of western Denver and bordered by the imposing belfry of Loretto Heights College, Fort Logan is unique in that it is a neighborhood with a view. In fact, the view was a major factor in Lieutenant General Philip H. Sheridan’s decision to locate a fort there in 1887. The early days of the fort, located nine miles from Denver proper, were tough and isolated. The first soldiers made permanent camp at the site on October 31, 1887, alongside Bear Creek, the present site of the intersection of Lowell Boulevard and Quincy Avenue. The centerpiece of the fort was its broad parade ground, an oval-shaped green space flanked by cottonwood trees and Victorian-style officers’ quarters. The fort’s first years saw several troop dispatchments quelling Native American uprisings, keeping order in a sometimes rowdy Denver political scene, and most importantly, traveling to Cuba during the Spanish-American War. The early 20th century saw the fort’s importance decline; it became a recruit depot and housed far fewer soldiers than before. Its buildings deteriorated during the interwar period, and the Works Progress Administration dedicated considerable resources to its revitalization in time for World War II. In 1946, however, Fort Logan was declared surplus and promptly closed.

The next chapter of Fort Logan’s history is somewhat similar to that of its northern neighbors; development occurred rapidly as land was sold off from its original owners. However, since Fort Logan’s original owner was the United States Government, the area’s story changed. Much of the fort’s land was transferred to neighboring municipalities for the purpose of constructing schools and parks. The future of the fort’s buildings, however, remained undecided. For a short time, the Department of Veterans Affairs used the property as a hospital until their new facility opened in Denver in 1951. Congress established the Fort Logan National Cemetery in the northwest corner of the old fort in 1950. The cemetery holds the remains of veterans from the Civil War, the Spanish-American War, World Wars I and II, the Korean War, the Vietnam War, the Gulf Wars, and the wars in Afghanistan and Iraq. Fort Logan continues to develop formerly vacant land, and it is estimated that the total burial capacity is 150,000. In 1960, the State of Colorado was deeded 236 acres for the establishment of the Fort Logan Mental Health Center, which continues to serve patients to this day. What was once Fort Logan now serves a mix of administrative, healthcare, and military functions far more diverse than its original purpose.

As Fort Logan grew into itself, the surrounding areas began to show signs of development. A former farm to the north of the fort was converted into the J.K. Mullen Home for Boys in the 1930s. In the next 20 years, the institution would transform itself from an orphanage into a high school; the last class to include orphans and paying boarders graduated in June of 1966. From then until 1989, Mullen operated as a day school for boys; the first girls arrived at Mullen for enrollment that year and continue to do so today. Denver annexed the property in 1958 as part of the city’s march southward. To the west, Pinehurst Country Club is a verdant, bucolic space stretching to Pierce Way. Formerly a farm, its owners converted the property into a golf club immediately after the close of World War II, when the sport skyrocketed in popularity among newer residents. The property was annexed into Denver in December of 1969, after four years of intense boundary disputes with Jefferson County. Early neighborhood advocacy for improved resources led to the construction of a fire station and a Pinehurst Park on Quincy Avenue in 1972. Kaiser Elementary School was built in 1974 and continues to serve the community to this day.

As Denver transitioned from being a pioneer town to a city with multiple economic and social layers, the city’s leaders saw economic and social opportunities in the establishment of a military outpost in the area. They petitioned the US Congress to this end, noting specifically the needs for civilian protection and for the enhancement of Denver’s social scene. In 1887, President Cleveland authorized funding for such a post and selected Lieutenant General Philip H. Sheridan to pick the site for the new fort. Many were surprised when Sheridan picked an area nine miles southwest of Denver, owing to its high elevation, scenic views, and large flat areas suitable for a parade ground. With this move, many Denver socialites’ dreams of military balls and other social events were severely dampened. In late October 1887, 22 men camped on the banks of Bear Creek and later set up camp at what was then informally known as Fort Sheridan. The next year saw major construction projects on the site, including the parade ground that Sheridan so desired. The outpost was not officially named Fort Logan until 1889, when General Sheridan lay on his deathbed and requested that a fort near Chicago (until then named Fort Logan) instead be named after him. The Fort Logan name was then transferred to Denver. General Sheridan’s influence lives on, however, in the town of Sheridan. By 1894, Fort Logan was self-contained, with accommodations for soldiers, a band, a hospital, three stables, a commissary, a post office, a bakery, a guardhouse, a greenhouse, a morgue, and a parade ground. Surrounding the parade ground were the officers’ houses: stately, red-brick Victorian homes which included basement wine cellars, brick window wells, and sandstone sidewalks. The largest of these at the apex of the circle belonged to the fort’s commanding officer.

The early 20th century was a successful period for Fort Logan. After the Spanish-American War, many soldiers returned with a new lease on life. As such, the soldiers constructed several tennis courts and a golf course, and parties occurred almost nightly. This festive environment was aided by Captain Allaire, an officer and society bachelor with a penchant for luxury. Many figures of high society, as well as some students from Loretto Heights College, frequented his glitzy events. Tough times began at Fort Logan largely due to bureaucratic ambiguity and neglect. In 1909, the post was downgraded to a recruitment depot, which it continued to be through World War I. It was reinstated as a training facility in 1922, but it only held about 350 soldiers, far from its original 750. The fort wove in and out of prominence in those years, which led to a general state of neglect at the physical level. Buildings deteriorated, and roads that were once well-maintained became impassable after rainstorms. As such, Denver newspapers often referred to the post as “Fort Forgotten.” Works Progress Administration funds somewhat rehabilitated the fort’s physical image in the 1930s, but it was too late. During World War II, Fort Logan became a subpost of Lowry Air Base, and German prisoners of war were housed in the barracks for several months. In 1946, the base was declared surplus by the army and closed the same year.

Today, many of Fort Logan’s buildings remain in use. Somewhat anomalous from the residential streets nearby, the oval-shaped parade ground now hosts local soccer games. The officers’ quarters are used by various entities of state and local government, and one Queen Anne-style home is now a museum. Much of Fort Logan’s land, so treasured by General Sheridan, has been sold off to development or is now part of the Fort Logan National Cemetery grounds to the northwest. While the fort itself may not have survived, the site remains a unique snapshot of early Denver history.

The cemetery at Fort Logan hosted burials long before its official establishment by Congress in 1950. Originally, the cemetery held the bodies of soldiers who died at the outpost, often of disease. However, the fort’s commanding officer could also authorize non-military burials; as such, several trappers, cowboys, and Native Americans have also been buried at the cemetery. A German prisoner of war, who died at the fort while being held there during World War II, also numbers among the non-military burials. The first recorded burial was of Mable Peterkin, the daughter of Private Peterkin, who was stationed at the fort, in 1889. On March 10, 1950, four years after Fort Logan was decommissioned, Congress authorized the establishment of Fort Logan National Cemetery and limited its size to no more than 160 acres. However, the cemetery has since expanded to 214 acres, largely due to a 2003 expansion meant to accommodate the increasing number of veterans’ deaths.

Fort Logan holds many notable veterans, including two recipients of the Medal of Honor: Major William E. Adams, who in 1971 during an attempt to evacuate wounded soldiers in Vietnam took enemy fire to his aircraft which eventually exploded, and First Sergeant Maxino Yabes, who in 1967 used his body to shield fellow soldiers from a grenade blast and then initiated a defensive attack before dying of his wounds. Seven Buffalo Soldiers are also interred at Fort Logan, as well as Karl Baatz, the German prisoner of war who died while being held at the fort in 1943. Two Navajo Code Talkers, Edward Denetdale Leuppe and John Werito, are also buried at the cemetery.

Memorial Day is a time of special significance at Fort Logan, as John Alexander Logan, for whom the fort and cemetery are named, started the tradition of Decoration Day (now called Memorial Day) in 1868. Flags from all 50 states are flown at the cemetery on Memorial Day, and services are held at the rock wall and central flagpole near the six-acre Veterans’ Lake.

Mullen’s history is in large part tied to the Fort Logan neighborhood. Like many private schools, Mullen was founded by a wealthy benefactor who bequeathed his name to the institution. John K. Mullen, an Irishman by birth, arrived in Denver in 1871 as an impoverished 19-year-old, soon working his way up the economic and social ladder in the flour-milling industry. John met Catherine, his future wife, while teaching Sunday school at St. Mary’s Catholic Church. Catherine had a penchant for helping the poor and needy as well, and together, the two were unstoppable. The pair had long discussed establishing a boarding school for underprivileged boys in Denver. After Catherine’s death in 1924, Mullen approached the Christian Brothers, a Roman Catholic order of professed and ordained religious men, with the idea of running a Brothers-staffed orphanage in Denver. In 1931, after John’s death, the Mullen Foundation found a suitable spot for the orphanage at the old Shirley Dairy Farm straddling Bear Creek, 420 acres south of Loretto Heights College. The Brothers and the first students moved into the newly established J.K. Mullen Home for Boys on April 8, 1932 - an institution which initially occupied just a single building. By 1935, attendance had grown to 50 boys. The orphanage rapidly expanded in the 1930s, buying up surrounding farms and running a successful dairy enterprise.

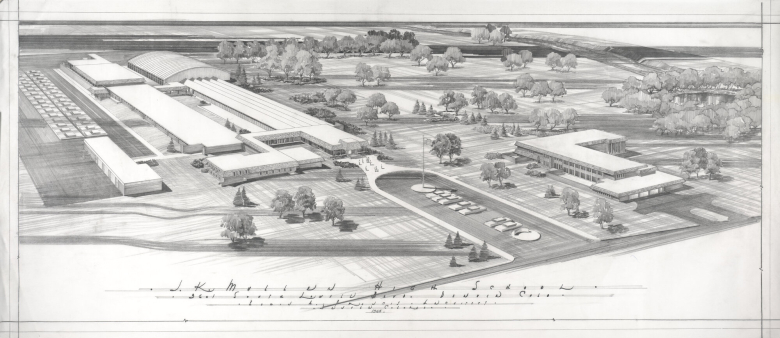

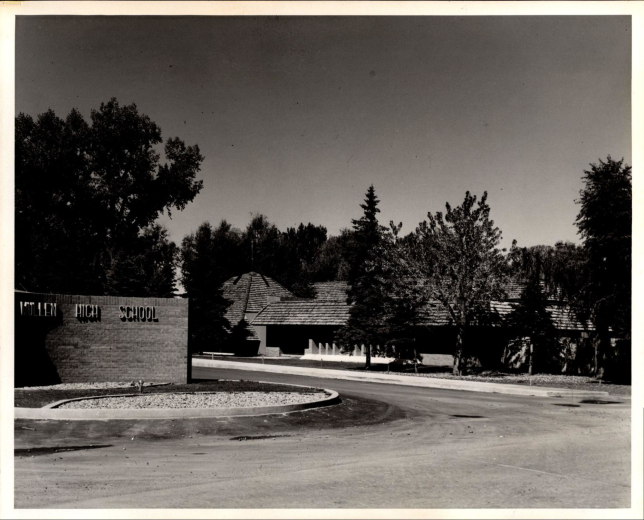

Along with its rural neighbors, the late 1940s and 1950s saw rapid changes at the Mullen Home. Southwest Denver’s farm era was rapidly coming to a close, and fire plagued the Mullen Home’s aging facilities. In 1953, the institution changed its name to J.K. Mullen High School, and in short order, the school was integrated into the larger Denver Catholic social and academic scene. The City of Denver annexed the property in 1958, and that same year, the school’s seniors graduated together with those from all other area Catholic high schools at the City Auditorium - a symbol that Mullen was no longer just a dairy farm run by orphans. US Highway 285’s construction in 1960 cut through Mullen’s property, and the school subsequently sold much of its northernmost property to developers as a result. The Christian Brothers purchased the school from the Mullen Foundation in 1980, and by 1989, Mullen admitted its first coeducational class. Fundraising campaigns begun in the 1990s initiated a drastic expansion of the physical plant and an upgrade to aging athletic facilities. Vincent Creco, the first lay principal, was chosen in 1993. The school continues to be sponsored by the Christian Brothers via the Board of Trustees, who carry out the executive functions on behalf of the order. In 2023, Mullen began construction on a multi-year master plan meant to revitalize the school’s physical plant.

The year is 1973. Southwest Denver is about 20 years old, and many of the area’s original residents have newly become empty-nesters. The public parks and pools are quieter, and the schools that once required multiple additions are now not quite as full. Fort Logan is now well into serving as the state’s psychiatric treatment center, but residents can remember the bugle call at morning and evening in the fort’s final years. The nuns at Loretto Heights are not donning the black habits they did just a decade ago, and some neighbors are discussing moving out of the home they purchased after the war in order to be closer to their children or to be farther from downtown Denver. More and more of their neighbors are Hispanic. Fast forward 50 years, to 2023. Southwest Denver is populated by older residents who stayed with their neighborhoods, alongside longtime Hispanic residents and a newer contingent of upper-middle-class millennial “flippers” who are renovating homes while preserving their vaunted mid-century modern character. Schools are burgeoning again, though their academic performance has somewhat fallen. Parks and pools are buzzing again, too. This is the Southwest Denver of today. It is a mix of ages, cultures, nationalities, languages, occupations, and political dispositions - after all, the area remains a paler shade of blue than the rest of Denver - and the story of each resident is far more diverse than it was 50 years ago. It remains to be seen what Southwest Denver will look like in 2073. It might have urbanized, it might have lost its distinctive charm. It might remain quite the same, but with larger houses and higher home values. Whichever path Southwest Denver takes, it will always have its history. What was once a smorgasbord of farmlands and then a symbol of the American Dream will continue to evolve well beyond the next 50 years.