~Written by Ryan Bell, University of Denver Internship Student ~

Known by some as the forgotten suburb of Denver, the Elyria-Swansea neighborhood can be difficult to pinpoint. Bisected by railroad tracks and Interstate 70, sandwiched between the National Western Center and the Nestlé Purina Factory, it seems as if the City of Denver has passed it by. This is a common feeling among Elyria-Swansea residents, who see their neighborhood history as one of institutional failure and systemic oppression.

Elyria-Swansea traces its roots to the late 1800s, when early developers and former miners platted and populated its streets. As factories grew up north of downtown, European immigrants took up residence and formed a working-class neighborhood complete with a school, grocery stores, and community organizations. The neighborhood transformed once again as Hispanic immigrants arrived. Concurrent with this transition was the building of Interstate 70 through the core of the neighborhood — a sign of city, state, and federal disregard for Elyria-Swansea. Today, the neighborhood’s residents continue to fight to save their community from threats in all directions, seeking to preserve a distinct way of life formed by decades of intersecting memories, identities, and cultures.

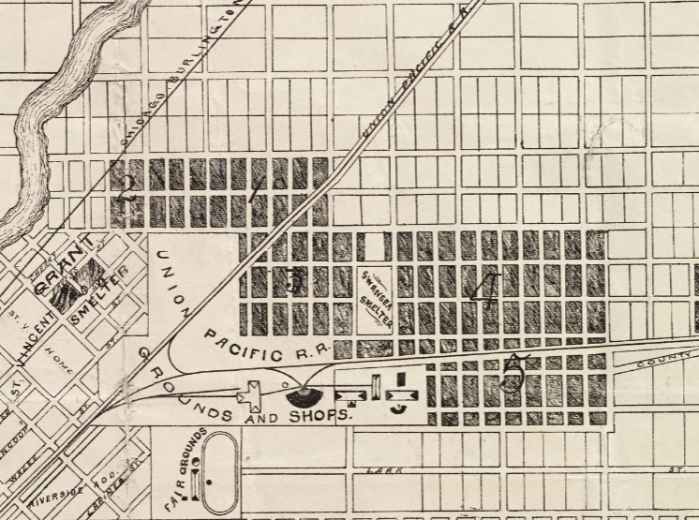

Bordered by the Platte River and Riverside Cemetery to the west, Elyria-Swansea extends eastward to Colorado Boulevard. Adams County forms the neighborhood’s northern border, and to the south, 40th Avenue separates Elyria-Swansea from the Cole and Clayton neighborhoods. The southwestern corner of the neighborhood extends to the far reaches of the River North (RiNo) District. However, Elyria-Swansea's geographic borders do not paint a full picture.

In the early 20th century, Elyria and Swansea were two distinct suburbs, with Elyria to the west and Swansea to the east. An oft-cited demarcation line between the two was Columbine Street until a railroad line was constructed bisecting the two communities; now, the common division line is York Street. As time went on, the two neighborhoods grew together and entangled themselves in the decades before they were bisected once again – this time into northern and southern portions, with the construction of Interstate 70.

Today, the eastern “Swansea” portion of Elyria-Swansea extends northward to the Adams County line and contains a large portion of the neighborhood’s population. Elyria, diminished by the encroachment of the Western Stock Show property and Interstate 70, has decreased in width from eleven blocks to about seven. The western border of Elyria, as platted in the late 19th century, was Lafayette Street. As the National Western Center encroached on the neighborhood in the 20th century, the boundary is now Brighton Boulevard, four blocks to the east.

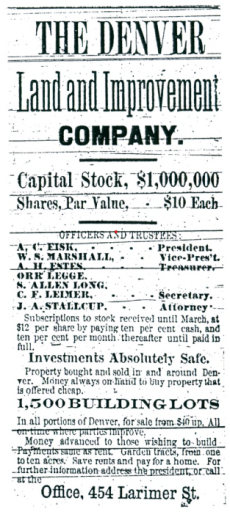

Both Elyria and Swansea are transplanted names. The western neighborhood was given the name Elyria after Elyria, Ohio, the hometown of the Denver suburb’s founder, Colonel Archie E. Fisk. Fisk fought for the Union Army during the Civil War before traveling westward to Denver. He quickly established himself as a major developer for the Denver Land Improvement Company, platting many of Denver’s early neighborhoods. Before its incorporation into the City of Denver, Elyria’s streets bore the surnames of the Company’s noted men including Fisk himself, for whom 47th Avenue was once named.

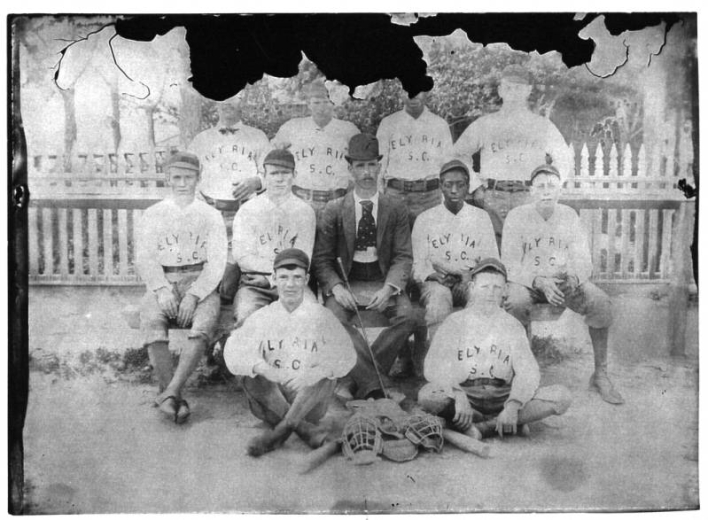

Swansea was named for a mining and seaport town in Wales by its early settlers. It was established around 1870 after the completion of the Kansas Pacific and Union Pacific Railroads, when a smelter was built at the junction of the two railroads for the purpose of extracting gold from iron ore. Upon their respective incorporations into the city of Denver, street names were changed to reflect the already-established streets of Denver.

Elyria was platted in March 1881 by Colonel Fisk for the Denver Land Improvement Company. Nine years later, after a substantial growth in population, Elyria voted to incorporate as a village in a hotly contested election held on July 21, 1890. Proponents of incorporation felt that the town would benefit from building codes and standardized zoning through the bylaws in what was then Arapahoe County. Opponents felt that their rural life and freedoms would be at risk if the town incorporated. While the election was close and the losing side only reluctantly admitted defeat, a certificate of incorporation was filed on August 2, 1890, and the town of Elyria was established.

Meanwhile, advertisements in the Denver Post show that land was for sale in Swansea around 1880, when the Lawson Company held well-publicized auctions to attract renters to purchase their own home. Swansea homes were built in the late 1800s and early 1900s by the development firm of Thomas, Downing, & Smith, with later additions continuing throughout the decades. Early advertisements speak of “artesian water” and “cable lines running through the cemetery” as prime reasons for prospective homeowners to eye Swansea over other suburbs.

A decade after incorporation, Elyria’s population stood at 1,384. Once disconnected from other neighborhoods, the City of Denver was slowly creeping towards Elyria from the south. As such, in 1902, the town of Elyria was annexed into the City of Denver. Annexation meant several things: Elyrians could not elect their own government officials, streets were renamed to conform to Denver’s already-established street grid, and fire and police services were outsourced to the city. Swansea’s journey to incorporation was much smoother than Elyria’s, and soon after, the neighborhood was annexed into the City of Denver in two phases: the first in 1883 and the second in 1902.

Much of the area’s early development occurred in Elyria; Hall’s 1901 History of Colorado deemed Elyria as “one of the fine suburbs of Denver…quite populous, well-built, and progressive.” By 1929, most of Elyria’s housing units had already been developed. After its incorporation into the City of Denver, Elyria’s residents began to suffer from increasingly poor environmental conditions. Sewage poured into the South Platte River from nearby factories, unpleasant odors from the stockyards and other industrial areas descended upon the town, and smog frequently enveloped the beleaguered suburb. From the beginning, Elyria-Swansea's location worked against its residents.

Early accounts indicate that there was no real boundary between Elyria and Swansea, and the two neighborhoods mixed frequently. Swansea continued to expand northward; many homes were built in the 1930s and 1940s. Elyria’s growth had stagnated by that time due to a lack of space on its northern and western ends.

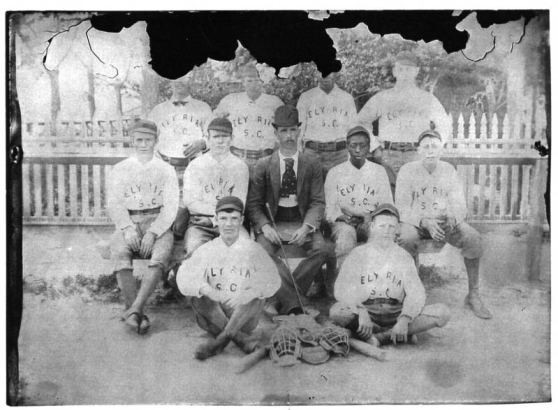

Elyria and Swansea’s first residents were miners. As such, the neighborhoods had a rough-and-tumble reputation which its occupants actively contributed to. Within several years of the miners’ arrival, however, the area began to be favored by industrial ventures because of its proximity to the South Platte River and its flat terrain. Stockyards, smelters, and dairies arose near the railroad tracks, and these new industries needed workers. The late 1800s and early 1900s saw large working-class populations employed in the emerging factories of north Denver. Most of these employees were new immigrants from Slavic and Eastern European countries: Poles, Slovakians, Slovenians, and Serbians as well as Germans and Italians in lesser numbers. These immigrants brought their cultures with them, forming tight-knit communities with families in their ethnic groups. Elyria and Swansea appealed to the immigrants due to the area’s cheap, plentiful housing and its proximity to industrial jobs.

According to the accounts of residents at the time, the environment in those days was harsh; men worked in the factories and struggled with alcohol abuse; women were charged with taking care of many children in substandard housing conditions; even the children were put to work early, often gaining full-time employment in factories by age 14. Regardless of the unfortunate elements of neighborhood life, Elyria and Swansea were seen as attractive areas for much of the early 20th century. Houses were small but well-kept, and young families benefited from nearby parks, grocery stores, and an elementary school.

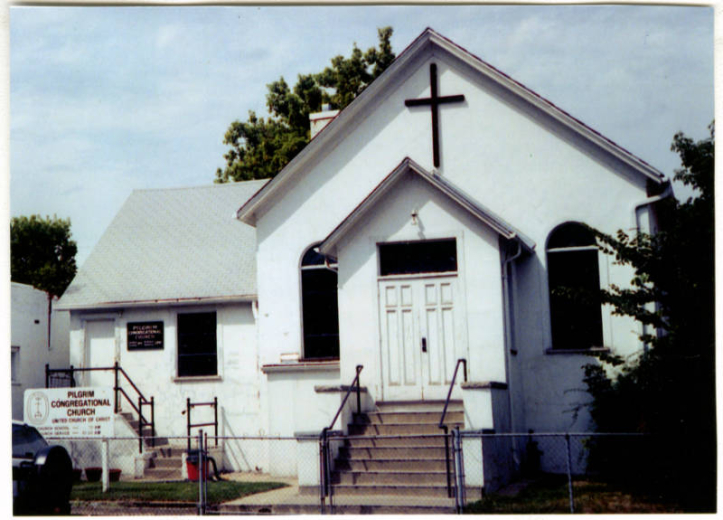

Religion and faith communities played a significant role in social cohesion and served as gathering spaces for different neighborhood groups. Pilgrim Congregational Church was and continues to be a fixture of the community. Before the demographic transition that began in the 1940s, Catholics attended St. Joseph’s, which catered to Poles, or Holy Rosary, which catered to Slovenians, in Globeville. As the Hispanic population in Elyria-Swansea increased, Our Lady of Grace Catholic Church in Swansea began to offer masses in both Spanish and English following the reforms of the Second Vatican Council. Our Lady of Grace continues the bilingual tradition to this day.

As the country underwent seismic changes following World War II, so too did Elyria-Swansea. Hispanic residents began to move into the neighborhood in the 1940s and 1950s. Some were from Mexico, while others were longtime residents of Southern Colorado, specifically Pueblo and the San Luis Valley. Many of these new arrivals were drawn to the area by jobs in the factories; industrial employers were also delighted to find a renewed source of cheap labor by those further down the socioeconomic ladder. Beginning in the 1950s, however, some of the largest slaughterhouses and dairies began to close. Elyria had been a meat-packing hub, while Swansea contained many dairies. Most of these plants closed, one by one, throughout the decade and into the early 1960s. At the same time, Eastern European American residents were experiencing an acceleration of social mobility and began a migration to the suburbs. By 1978, the Hispanic population comprised the majority of Elyria-Swansea's residents.

Neighborhood Stories: Bettie Cram

“The packing houses, eventually, quit, because it got very modernistic. It was such a shame, because all of the workers in the packing houses and in the Livestock Exchange Building—most of the people were from this area. On their lunch hours, they would ride their horses home—and it was just a fun, fun time that I felt I experienced in those years. After the packing houses closed down, Elyria really kind of fell apart.”

The construction of Interstate 70 through Elyria-Swansea from 1960 to 1964 drastically changed the area’s character and composition. Despite loud protests from the neighborhood’s residents, the highway cut through the neighborhood in the approximate location of 46th Avenue. A viaduct, raised from the ground on concrete supports, began to take shape in the place of demolished homes and businesses. Swansea Elementary School, once surrounded by residences, was now in the shadow of a concrete bridge overlooking its playground. The change brought about by Interstate 70’s construction is difficult to comprehend. Now, rather than being divided into two neighborhoods by the railroad tracks near York Street, the interstate further sliced the area and virtually cut off the southern blocks from their northern neighbors.

Neighborhood Stories: Susan Knapp

“When I-70 was built, they told us—they told my dad and grandfather for 10 years that they were going to be putting a road through, and they’d be buying the property. During that 10 years, they went ahead and thought: They’re never going to do this. So they went ahead and built on the corner, a little restaurant, a coffee shop, and a liquor store that my uncle ran. So they had this brand-new building, they’d only been there two or three years when they finally did go ahead and buy the property to do I-70.”

The construction of Interstate 70 had other effects as well. First, more homes were demolished in the years following the highway’s construction to make way for business and industrial enterprises catering to highway travelers. Landlords began to buy up homes as longtime residents moved out, and benefited from declining home values and an increasing Spanish-speaking population in need of inexpensive housing. The well-kept homes emblematic of decades past became less common as property values crashed. Landlords often used their tenants’ properties as dumping grounds and junkyards, and the City of Denver was slow to respond to complaints of improper yard maintenance.

As Denver grew during the 1970s and 1980s, traffic continued to increase, often spilling over onto Brighton Boulevard during peak rush hours. Landscaping and noise abatement procedures, promised to Elyria-Swansea residents at the time of the interstate’s construction, were never completed. According to a 1979 Denver Post article describing the area’s plight, “An army laying siege couldn’t be more effective” at closing the neighborhood off from its surroundings. Elyria was often forgotten after the interstate’s construction, even by officials at the City and County of Denver. Denver Planning Office maps did not show the neighborhood, often conflating it with Swansea even into the late 1970s.

By 1980, 60.4% of Elyria-Swansea's residents were Hispanic, 32.4% were white, and 7.17% were Black. By 1990, 70% of Elyria-Swansea's residents were Hispanic. This trend has continued, increasingly showing a marked contrast to the majority-white City and County of Denver of which the neighborhood was a part. However, there is an increase in newspaper coverage of Elyria-Swansea beginning in the mid-1980s. Much of this was caused by neighborhood advocates working on behalf of their community, alerting a less-than-receptive public about the plight of their neighborhood. An influx of Mexican nationals in the 1980s and 1990s kept the area’s population stable and increased the neighborhood’s rates of home ownership and maintenance, according to a 1997 article in the Denver Post.

The eastern creep of Denver’s suburbs in the 1980s and 1990s resulted in a steadier flow of traffic on Interstate 70 as the city’s wealthier residents and newcomers alike were drawn to new construction in Denver’s eastern suburbs. The construction of Denver International Airport in the early 1990s exacerbated the intersecting concerns of traffic, pollution, and noise in Elyria-Swansea. As the original viaducts constructed in 1964 began to crumble, state and federal feasibility studies explored widening the viaducts to accommodate more traffic. A cantilevered toll lane was even considered in the early 2000s, with metal struts that would balance more cars further above the neighborhood.

Neighborhood Stories: Tony Garcia

“Purina says the stock show causes the odors. Stock show says it’s the refineries, and blame keeps getting passed around. But you don’t have to be a rocket scientist to know that – when the air smells this bad – it can’t be good for me or my kids.”

Denver Post, January 20, 1997

Adding to the highway’s pollution concerns was the Asarco heavy metal smelter, which belched exhaust fumes into the surrounding area. This, coupled with the Purina Chow Factory’s emissions, constituted a “triple threat” of health concerns. The neighborhood also became a dumping ground for heavy industry and a transportation site for toxic waste. In 1989, Elyria-Swansea's residents successfully fought to prevent a medical waste incinerator and a radium-tainted earth weigh station from being constructed in their neighborhood. Other actions, however, were less foreseeable. On March 29, 1995, a railroad tank car traveling through Elyria-Swansea leaked hydrochloric acid, sending a cloud of toxic fumes into the neighborhood. Those living near the tracks which bisect the neighborhood were evacuated. For Lorraine Granado, a longtime neighborhood resident, this event proved to be a tipping point. She and others filed suit against the Vulcan Materials Company, the owner of the tank car, which resulted in a $200,000 settlement and the establishment of a park next to the Swansea Community Center. The park was renamed the “Lorraine Granado Community Park” in her honor in 2020.

By the 1990s, Elyria-Swansea was markedly different, if not unrecognizable, from its first days a century earlier. The industrial era officially came to an end when the Bar S Plant, the last meatpacking plant left in Elyria-Swansea, closed in 1996 and lost the community about 400 jobs. Meanwhile, in the mid-1990s, tensions flared between residents of Elyria-Swansea and the administration of the National Western Stock Show. A new $11 million Events Center opened in 1995 chewing up several blocks of Elyria to Baldwin Court. The Valdez-Perry Branch of the Denver Public Library opened in the fall of 1996 as part of a deal struck by the neighborhood that allowed for the events center to be built.

About 7,200 people live in Elyria-Swansea today, with the majority located east of York Street and the bisecting railroad tracks. According to the 2010 census, about 84% of Elyria-Swansea residents are Hispanic, as opposed to the City and County of Denver, where about 32% of residents are Hispanic. The neighborhood’s ethnic composition is key to understanding the structural disadvantages that come with residing in Elyria-Swansea today. A 2017 report showed that Elyria-Swansea's zip code, 80216, is the most polluted in the country. This comes as no surprise given the historic concentration of heavy industry in and around the neighborhood. Even with the construction of new parks in recent years, which has added green space to Elyria-Swansea, the neighborhood still has one of the lowest tree canopy rates in Denver, a measure often associated with negative health outcomes.

In the past five years, Elyria-Swansea has once again undergone widespread changes, in some ways as disruptive as the construction of Interstate 70 more than fifty years ago. After decades of feasibility studies, The Colorado Department of Transportation (CDOT) began construction on the Central 70 Project, designed to renew a 10-mile stretch of highway between Chambers Road and Brighton Boulevard, the latter being on the westernmost edge of Elyria. Since the passage of the National Environmental Policy Act (NEPA) in 1970, federal construction projects must receive input from local stakeholders before formulating a design. While federal officials and administrators from CDOT held listening sessions for community members in Elyria-Swansea prior to the approval of the final design, many residents saw the eventual approved plan as mirroring past injustices. Additionally, the memory of Interstate 70’s construction is not long removed from the public consciousness, and a longtime distrust of city, state, and federal officials meant that the residents of Elyria Swansea demanded community input during the design and construction phases of the Central 70 Project.

After considering options like reconstructing the overhead viaduct, digging the highway into a ditch, and even rerouting the interstate northward away from the neighborhood, CDOT decided to move forward with the below-grade route. A concession granted to Elyria-Swansea neighborhood residents was the construction of a cover park over the newly created ditch. The park, completed in November 2022 to great fanfare, spans between Columbine and Clayton Streets and includes soccer fields, green space, and an amphitheater. The cover park, which some see as the physical and conceptual equivalent of a band-aid, is not a complete reconnection of the neighborhood. In the eyes of city and federal officials, however, it is a step in the right direction.

Neighborhood Stories: Judy Montero

“You have raised your family; you’ve purchased a house here. They go to school, they work. People worship here; they walk through the neighborhoods. It’s not a dumping ground.”

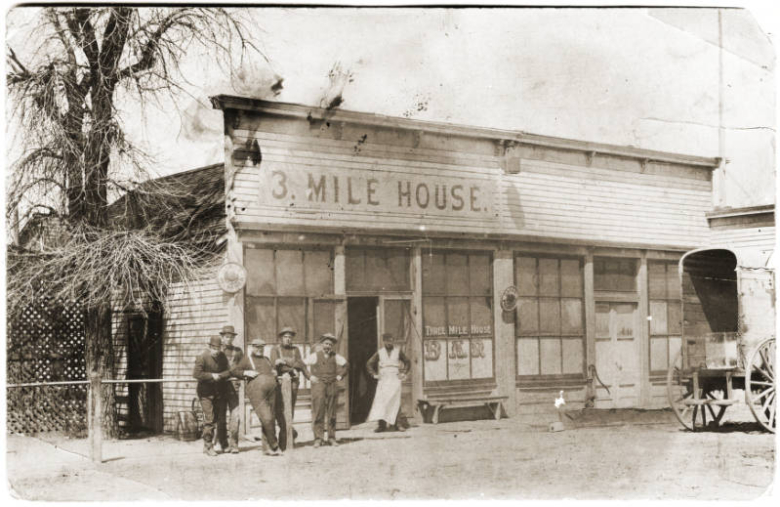

This structure was a nexus of commerce and social life in Elyria’s early days. Built before 1881 and located at 48th and Gilpin, the establishment served as a farm, dairy, inn, saloon, and social hall. The 3 Mile House has since been demolished; like many properties in Elyria, the property fell prey to the expansion of the National Western Center. Today, the site sits vacant and is located close to the 48th and Brighton National Western Center RTD (Regional Transportation District) Station.

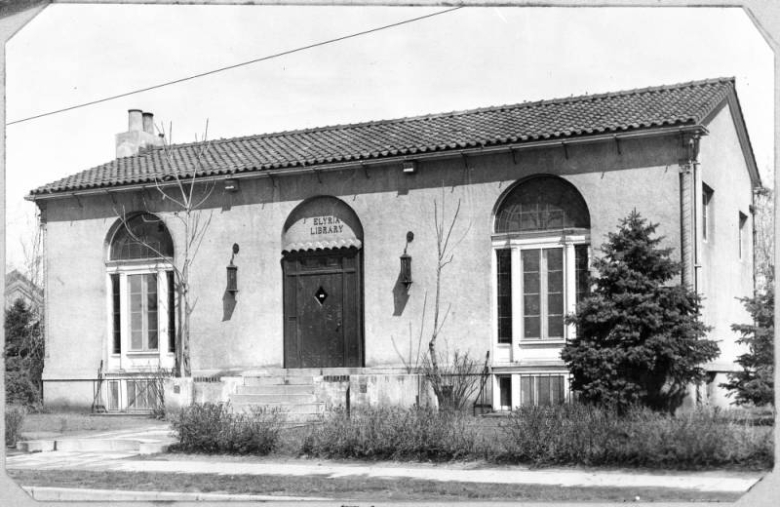

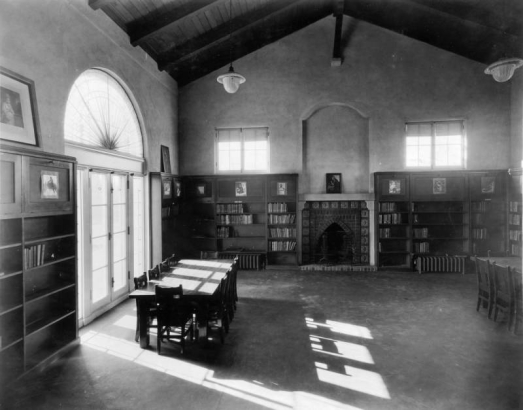

Located at 1901 East 47th Avenue on the corner of 47th and High Street, the old Carnegie Library mirrors the Spanish Revival style of the Elyria schoolhouse on the same block. Designed by Henry J. Manning, the building was praised at the time of its 1923 completion for its large windows and fireplace. The library was funded jointly by the Carnegie Corporation and various stockyards in the area. However, it closed in 1952 due to years of chronic under-circulation. It has since been transferred to private hands, and today is a recently renovated home.

Located at the corner of East 47th Avenue and Brighton Boulevard, the town hall was the pride of the once-independent Elyria. Over the years, it served alternatingly as the chambers of the town council (before Elyria’s annexation into the City and County of Denver), jail, theater, and fire house. It was built in 1895 for the newly established Elyria town council, which presided over some of the hottest debates involving zoning and annexation. It was renovated in 1904 so that it could serve as a firehouse, as Elyria had no need for a town hall after being annexed. The building began to show its age and was demolished in February 1940.

Riverside Cemetery has a rich history dating back to its first interment in 1876. Riverside was the brainchild of several of Denver’s prominent early businessmen, who believed that City Cemetery (now Cheeseman Park) was an eyesore unbecoming of their social status. To rectify this, they purchased several acres on a high bank of the South Platte River north of the town. Fairmount Cemetery bought Riverside in 1900 and immediately began to invest in the property. They commissioned the renowned architect Frank Edbrooke to design an office, chapel, and crematorium all under one roof.

This building was eventually constructed in the mission revival style and opened in May 1904. The inclusion of a crematorium in the building was notable, as Riverside was one of the first cemeteries in the West to offer cremation services. The “Head House” which is still attached to the back of the Edbrooke building was originally a potting shed for a florist shop; it is now used for storage.

Another historic structure in Riverside Cemetery is the Old Stone House, which has not been in use since 1904. Designed in the Richardsonian Romanesque style, the Old Stone House was built with limestone from a Colorado quarry. Its exact use and construction date remain unknown, though it appears in a photograph of the cemetery taken around 1885. By 2004 the building had fallen into such disrepair that the roof was leaking, and so a cap was placed over it with funding from the Colorado State Historical Fund. Today, Riverside is devoid of irrigation and spans about 77 acres.

Regardless of the cemetery’s physical condition, it holds some of the state’s most notable figures from the 19th and 20th centuries. These include: Clara Brown, Silas Soule, Miguel Antonio Otero, Augusta Tabor, and Governor John Evans. Additionally,

- Clara Brown (1800 – 1885), a former slave and the first Black woman to cross the Great Plains. She opened a highly successful laundry business in Central City and sent funds to assist former slaves relocating to Colorado.

- Captain Silas Soule (1838 – 1865), a Union Army abolitionist, conductor on the Underground Railroad, and a close friend to John Brown. Soule refused to participate in the Sand Creek Massacre and later testified against his military superiors. In retaliation, he was assassinated and laid to rest at Riverside.

- Miguel Antonio Otero (1829 – 1882), one of the New Mexico Territory’s most prominent businesspeople and politicians best known for providing the Confederate Army with the resources needed to complete their 1862 Sack of Albuquerque. Otero County in southeastern Colorado bears his name.

- Augusta Tabor (1833 – 1895). Originally from Maine, Augusta married Horace Tabor and the two established a successful enterprise in Leadville after Horace struck a silver vein. When Horace became lieutenant governor of Colorado in 1878, Augusta moved to Denver and oversaw construction of the family mansion. Horace soon left her for the famous Elizabeth “Baby Doe” McCourt, but Augusta remained a noted philanthropist in her own right until her death.

- Governor John Evans (1814 – 1897), the noted physician, politician, and businessman. Evans was the territorial governor of Colorado from 1862-1865. He was forced to resign the governorship due to his role in condoning the Sand Creek Massacre, which included honoring its perpetrator, Colonel John Chivington, for his bravery during the killing. He is also noted for founding the University of Denver, an institution still grappling with his legacy.

- Riverside Cemetery is also the burial place of over 1,200 Civil War veterans.

The status of religion in Elyria-Swansea has changed with the neighborhood. One of the first religious establishments in the area was Pilgrim Congregational Church, founded in 1882 in a tent on land now the National Western Center. It moved to its present location in August of 1890. The congregation was Eastern European in its first years, but as the demographics of Elyria transitioned to include a Hispanic population, Pilgrim Congregational Church changed too. Today, the church has two Sunday services, one in the morning for English-speakers, and one in the evening for Spanish-speakers. Its small congregation is still active within the community.

The neighborhood’s first school building was erected in 1885 at the corner of Fisk Street (now 47th Avenue) and Marshall Street (now High Street). The square building had a capacity of 54 desks and resembled a large house. For most of its existence, the building housed Kindergarten, 1st, and 2nd grade. Older children would attend elementary school in Swansea.

Elyria’s second elementary school was built in 1924 because the old building was too small for the neighborhood’s burgeoning school-age population. It was directly north of the old school at 4725 High St. The building’s last educational function was as the neighborhood kindergarten due to overcrowding at Swansea Elementary. However, as Elyria received less and less attention from the City and County of Denver, so did its school. After closing and being abandoned in the 1970s, it was purchased in 1989 by the Su Teatro theater troupe, an association born out of increased interest in Hispanic life and culture in the 1970s. The old Elyria School soon hosted a full season of performances by Su Teatro, and the building became a gathering place for those seeking to learn more about the history and culture of the neighborhood. Su Teatro moved out of the building in 2010 to a larger space on Santa Fe Drive. The building is now occupied by Tepeyac Health, a Latino-led non-profit healthcare clinic.

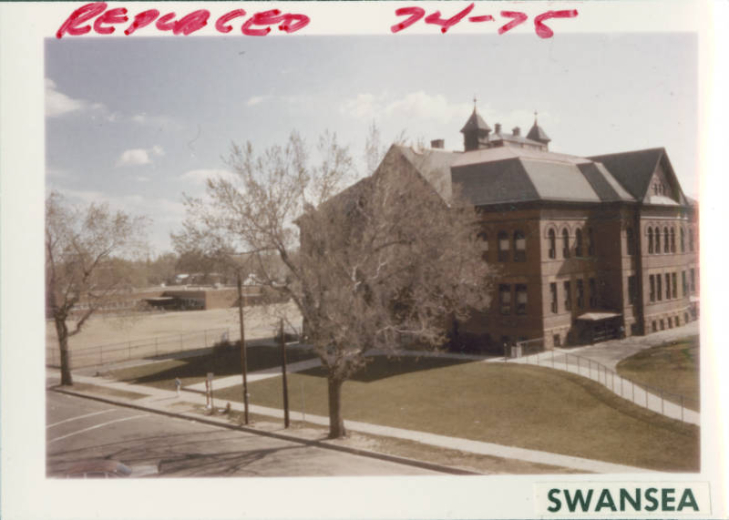

Education in Swansea has continued uninterrupted for more than 130 years. The first Swansea School was built in 1891 for the neighborhood’s earliest inhabitants. Due to space limits at the Elyria School, Elyrians above the age of ten also attended Swansea Elementary. The first Swansea School building was three stories, including a partial basement. It served the community for many years and was party to some suspicious incidents. For instance, on the night of June 6, 1973, a bomb was thrown into the school’s stairwell. While nobody was injured, the bomb did about $1000 in damage to the structure and was one in a series of bombings affecting the area’s schools that year. An annex to the old school was built in 1958 as a separate structure, and the 1964 construction of Interstate 70 caused the east-west viaduct to loom directly to the south of the school’s playground. The 1958 structure was gradually expanded over the years as the 1891 building aged beyond repair. The new school underwent its final expansion in 1976, the same year that the old school was torn down.

The new building was much larger than the old one, and its one-story blonde brick façade introduced a more modern architectural style to the neighborhood. The dedication ceremony took place on May 12, 1976. In the 1970s, under Denver's school desegregation program, Swansea was paired with Holm Elementary School in the Hampden neighborhood. Swansea Elementary enrolled all 1st through 3rd graders from the two neighborhoods, while children in 4th through 6th grades were bussed to Holm Elementary. Kindergarten was held at the Elyria school thanks to Swansea Elementary’s overcrowded classrooms. As Elyria-Swansea became predominantly Hispanic, bilingual teachers became increasingly common at Swansea Elementary.

By the 2010s, conversations were underway to discuss how Swansea Elementary would be impacted by the planned expansion of Interstate 70. After significant efforts by community activists, the Colorado Department of Transportation granted a concession to the impacted school: a cover park would be constructed over the interstate and would include soccer fields designated for exclusive use by Swansea Elementary during school hours. A 2017 renovation of the school building by Anderson Mason Dale was designed to correspond with the cover park addition. The redesign included two new early childhood education classrooms, a new entry to the school, new ventilation and air conditioning systems, and new windows and doors in classrooms. These recent investments in Swansea Elementary are the result of sustained community concern for a school that was once one of the most underfunded in Denver. The school serves around 560 students in its updated building.

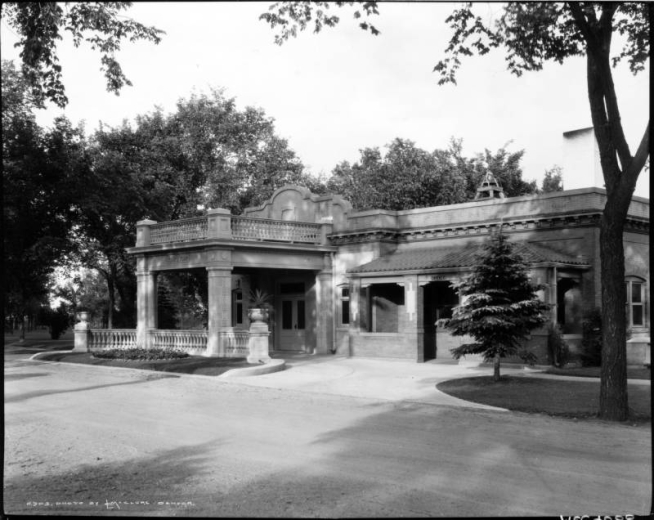

The National Western Center’s Livestock Exchange Building, while separated by railroad tracks and stockyards, is a notable building in Elyria. The redbrick structure, replete with neoclassical elements and a decorative façade, was built in three phases. The original building, constructed in 1898, is in the center and barely visible to the public. Damaged in a fire in 2003, it is no longer occupied. The eastern wing, built in 1916, is the most recognizable and elaborate. Its four three-story fluted ionic entry columns support a parapet inscribed with "The Denver Union Stock Yard Company." The last addition, built to the west in 1919, is less elaborate than the eastern façade. The 1916 building is untouched; wood, trim, and marble from the building’s construction still grace the interior. Chalkboards where livestock prices were displayed still hang on the building’s second floor. For many years, the building was occupied by the Denver Livestock Exchange, a nonprofit which oversaw livestock sales in Denver.

Remnants of the building’s original tenants are common. The first floor holds several safes from the Stock Yards National Bank, which carried out livestock transactions with ease. The Colorado Brand Inspection Board occupied the building from 1906 to 2015, and in recent years, private tenants have leased it too. The recent redevelopment of the National Western Center has drawn increased attention to the building, as proponents of the redevelopment see commercial potential for the century-old structure. The Denver Stockyard Saloon, a bar and restaurant in the style of a 19th century western watering hole, serves patrons to this day in the western wing of the building.

Neighborhood Stories: Bettie Cram

“Restaurants in the Livestock Exchange Building were great. I worked at one place called the Lowell Commission Company, and met many, many wonderful people that I’m still acquainted with. Many of the people that worked in the area have come back into the neighborhood, as I mentioned before.”

Today, a search for “Elyria-Swansea” on the internet produces articles and resources from several local news organizations of repute. This stands in marked contrast to coverage several decades ago, when articles about the neighborhood were relatively rare. This increased attention to Elyria-Swansea has had positive and negative effects. Today, Elyria-Swansea still reaps the results of years of deferred maintenance by the City and County of Denver, but community activism has led to the neighborhood being given greater priority than ever before. However, rising home prices and increased costs of living have led developers and others to see Elyria-Swansea as ripe for gentrification. Thanks to its proximity to the River North (RiNo) Neighborhood, Elyria-Swansea has seen rising home and apartment prices on its southern border for several years. The effects of such development remain to be seen, but it is clear that the neighborhood may be on the cusp of yet another transformative era in its history.

Sources

- History of Denver, with outlines of the earlier history of the Rocky Mountain country (Smiley, 1901)

- Place Names of Colorado

- DPL Oral Histories of Globeville, Elyria, Swansea (GES)

- DPL Subject Index Cards for "Elyria"

- Colorado Historic Newspapers Collection

- City of Denver Real Property Records Search

- Denver Assessor Records Index Map: Late 1800s To The 1950s

- Swansea Elementary School Community History

- Stories of Elyria (PBS, 1992)

- RiNo Historic Neighborhoods: Elyria and Swansea

- Elyria: Denver's Forgotten Suburb (MacMillan, 2004)

- Central 70 Reevaluation Report (CDOT, 2019)

- Central 70 Environmental Impact Statement (CDOT, 2016)

- Elyria-Swansea Neighborhood Assessment (City and County of Denver, 2003)

- I-70 work made them move, and many could not stay in Denver (Denverite, 2018)

- National Western Center Master Plan (2017)

- Jenny Santos Oral History (Denver Public Library, 2013)

- Betty Wonder Oral History (Denver Public Library, 2013)

- Bettie Cram Oral History (Denver Public Library, 2013)

- Judy Montero Oral History (Denver Public Library, 2013)

- Lorraine Granado Biography (Denver Public Library)

- Bettie Cram: A historic voice in an evolving landscape (Colorado State University, 2017)

- Exploring Preservation Action in Old Elyria (Historic Denver, 2022)

- A giant vault, fancy urinals and unique architecture: A look at the Denver Livestock Exchange building’s past - and potential future (Denverite, 2022)

- History of the Riverside Chapel, Crematorium And Office (Riverside Cemetery)

- History Of The “Old Stone House” (Riverside Cemetery)

- Pilgrim Congregational Church (Discover Denver)

- Globeville and Elyria-Swansea just doubled their voting power on the National Western Center board (Denverite, 2023)

- Bettie Cram, a pillar of Elyria Swansea, dies at 98 (Denverite, 2020)

- Don’t want the I-70 expansion? CDOT director tells Ditch the Ditch activists to sue (Denverite, 2017)

- Interstate 70 Construction Timeline (CDOT)