~Written by Angelina Scolio, University of Denver Internship Student ~

From grazing land for a dairy farm to a bustling aviation hub, to the one of the largest urban redevelopments; the Central Park neighborhood, formerly known as Stapleton, presents a long and storied history. By overcoming challenges and embracing change, the neighborhood has transformed itself into a vibrant community, with repurposed landmarks like the old control tower and Hangar 61 underscoring its innovative spirit. Today, Central Park is one of Denver's newest and largest neighborhoods and is a lively tapestry of the past and present.

Before the neighborhood and the airport, most of the Central Park land was used as grazing space for the Windsor Dairy farm. The Windsor Dairy company was brought to the forefront of the Colorado dairy industry by H. Brown Cannon who acquired the company in the late 19th century. Cannon moved from his native Michigan to Colorado in 1888 and immediately began working in the dairy industry. After purchasing the company, Cannon galvanized Windsor Dairy, receiving high regard for the quality of his product and becoming the most sought after dairy producer among Denver elites. Cannon's impact on Denver is best experienced now in LoDo on the Dairy Block, where the old Windsor Dairy processing building stands and houses popular shops and restaurants. None of this notoriety would have been possible without the acres of Central Park cattle-grazing land Brown owned outside of the city.

The Rocky Mountains, arguably Denver's greatest resource, was also its greatest setback at the dawn of American transcontinental transportation. During railway development, engineers felt that the Rocky Mountains were impenetrable and opted to place their connections hub in Cheyenne because the railway could more easily navigate the less intense Wyoming Rockies. When the United States Postal Service began the federal air mail carrier service, Denver ran into the same problem; Cheyenne was again chosen over Denver because the USPS believed their planes could not manage the high altitudes of the Colorado Rockies.

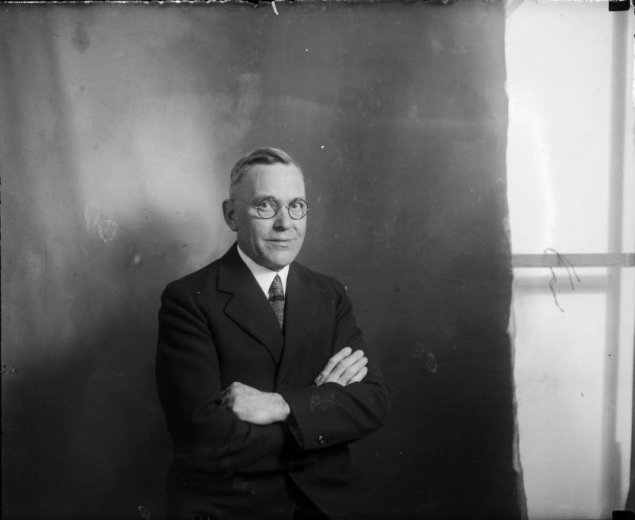

When Mayor Benjamin F. Stapleton came into office for his first of five terms in 1923, he had a plan to change Denver's unsatisfactory relationship with transportation by building a municipal airport. Working with the Commissioner of Parks and Improvements Charles D. Vail, Stapleton began his plan to consolidate and standardize Denver's air traffic. Vail and Stapleton found two prospective plots of land on which to build the airport. The first option was to expand Lowry Air Field (later known as Combs Airpark), which housed the 120th National Guard squadron. The second option was to purchase the Windsor Dairy Farm from Stapleton’s personal friend, H. Brown Cannon, as well as other smaller parcels of land along Sand Creek. While there was no direct evidence of corruption found, Stapleton pushed hard for the city to purchase Cannon’s land, arguing that it was just far away enough from any developed area (6 miles from the city center) and the land prices were more reasonable compared to the ones closer to downtown. On March 19th, 1928, the city of Denver approved the purchase of the Windsor land as well as another plot of land from the estate of Samuel Hertzel to build the new municipal airport.

The land deal and the airport were met with fervent opposition from Denverites. According to the Rocky Mountain News, the aviators working with the city on the project almost unanimously opposed the use of the Sand Creek land for the airport. Other high ranking Denver officials outwardly opposed the Sand Creek lot for a multitude of reasons. They argued that the soil on the lot was too sandy to build an airfield on, that the location was too far from the city to be serviceable, and some officials opposed the very idea of using taxpayer dollars to build at all. No party was more openly resistant to the airport than the Denver Post, dubbing the endeavor “Stapleton's folly.” The Post also ran numerous articles that highlighted issues with the project; citing a local real estate agent, the Post reported that the “Sand Creek land was not worth half of the $125,000 that [was] proposed to be paid for it.” The Post went as far as to attack the mayor himself, asserting that “against the wishes of every aviation authority in Denver, Mayor Stapleton purchased the Sand Creek site from his friend H. Brown Cannon. In purchasing the Site, the mayor paid off a political debt of many years standing.” Despite such ardent opposition, Stapleton prevailed and on March 25th, the city paid $143,013.37 for the land.

After the budget approval, construction began immediately and the airport was completed and operational by the fall of 1929. At the dedication ceremony, the municipal airport was called “one of the finest in the land” and received the prestigious A-1-A rating from the Department of Commerce. While the airport itself was cutting edge, it initially struggled economically. With the Great Depression looming, the Rocky Mountain News reported that the airport averaged a $7,000 monthly income in its first nine months. This frustrated citizens and city officials alike, since the project was a $430,000 investment. Luckily, business almost inexplicably picked up in the last three months of the year and, with the city's commitment of $25,000 a year for updating, the Denver municipal airport was well on its way to becoming a regional transportation hub.

Hitler’s rise to power brought with it a heightened concern for U.S. domestic security. In 1934, the Federal Aviation Committee called for 20 air bases to be constructed around the country for domestic air defense. Denver was one of the few inland cities selected for this defense initiative because the Denver Federal Mint held the nation's largest supply of gold and was only conceivably vulnerable to attack by air. The Lowry Airfield was constructed in 1937 as part of this initiative and worked in tandem with the Denver Municipal Airport (DMA) during the war. DMA was also renovated during the war: runways were expanded to accommodate the largest US bombers, the control tower was updated, and President Roosevelt allotted $110,000 to double the size of the National Guard hangar. One major use for the hangar was modifying commercial planes into bomber aircraft. By the end of the war, the hangar had grown to over four times the size of DMA’s original airport hangar, and in peacetime was turned over to the city once aircrafts no longer needed modifications.

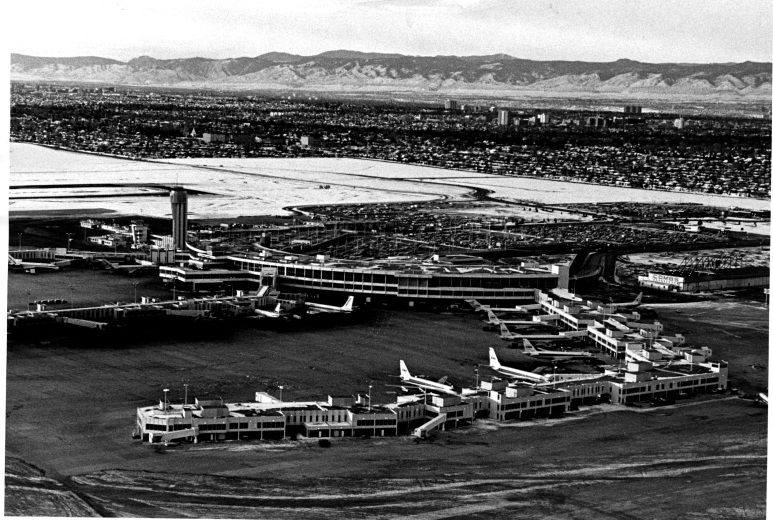

During the Postwar era, Denver became an important location for aviation due to its proximity to military bases and access to the west. Stapleton predicted a major aviation boom for the city and in 1946, proposed a $1 million plan for renovations to the airport to keep up with the demand. However, Stapleton finished his last term as mayor in 1947 and the new mayor, J. Quigg Newton, put a stop to the plan. Instead, Newton assembled his own team to study the airport and make gradual changes throughout the following decade to prepare the airfield for the Jet Age. Newton’s agenda included adding and elongating runways, expanding terminals, and updating the control tower, among other improvements. Even though Newton opted to overhaul Stapleton’s plans, Newton recognized the former mayor's commitment to the airport and supported the renaming of Denver Municipal Airport to the Stapleton Airfield in 1964. Newton's master plan was completed in 1966 for the price of $5 million. As the plan was reaching completion, the city was once again looking to update the airport to accommodate jumbo jets and supersonic air travel, which required significant amounts of additional funding and land that was not available.

The Stapleton Airfield expanded into the land of the Rocky Mountain Arsenal, but this solution to the issue of limited land was only temporary. Even with the new expansion, there were problems. Residents of the adjacent Park Hill neighborhood complained about safety concerns and noise pollution from the jets, and were among the first advocates for a new Denver airport. Air traffic controllers also had concerns about safety and overcrowding within the airport. After observing air traffic employees in the control tower, a Rocky Mountain News reporter described the work as “one of the most difficult, ulcerous and demanding jobs modern technology has managed to create.”

In 1979, the major U.S. airlines established the norm of the “hub and spoke” model for air traffic, in which transport is optimized by having a central hub where passengers and cargo are then transported to the smaller spokes. The four major airport hubs became Dallas/Fort Worth, Atlanta, Chicago, and Denver. This model was the nail in the coffin for the Stapleton Airport. In order to accommodate the immediate expansion necessary for this role, the airport would have had to absorb all of the Rocky Mountain Arsenal land – an option that was only briefly entertained. Instead, planners were forced to abandon Stapleton altogether and begin work on an entirely new airport. The last take-offs and landings at Stapleton took place on February 27th, 1995 and the new Denver International Airport opened at 12:01 A.M. on February 28th.

With Stapleton’s closure impending, in 1988 Mayor Federico Peña created the Stapleton Tomorrow Group, which was tasked with thinking broadly about the future of Stapleton. The group was made up of business and civic leaders, as well as neighborhood activists and citizens. Many ideas for alternative purposes for the former airport were discussed, including a bulk sale of the land, an aircraft maintenance facility for Continental Airlines, and even converting the old airport into a new football stadium. Sam Gary, a Denver oilman and philanthropist, latched on to the bulk land sale idea and was instrumental in formulating a plan for redevelopment. Gary gathered $4 million – with $2 million coming from his own pocket – to create the “Green Book,” an in depth plan outlining Stapleton’s development into a residential area aiming to break the pattern of urban sprawl with a planned community that emphasized urban renewal. Mayor Peña described Gary’s role in the Stapelton project saying “Sam was the key, he was the one willing to fund the early planning and the strategic thinking. Without Sam G’s support we would not have been able to pull this off. The city was broke… he was a visionary leader.”

With the Green Book in hand, the city began searching for developers for the upcoming Stapleton neighborhood. Instead of going with the highest bidder, the city looked for a development company who presented the most promising long term commitment to the project; their winner was Forest City Development. The deal was carried out using tax increment financing. This meant that Forest City would front the costs for roads, utilities, and other infrastructural elements, and the city would reimburse the company once homes began to sell and property tax revenue came in. This was a particularly fortuitous decision on the part of the city, considering the impending housing crisis.

Demolition of the old airport began in 1999; the removal process produced enough concrete to fill Mile High Stadium six times over, according to the Denver Post. The materials were managed and recycled by Recycled Materials CO., out of Arvada. It took them six years to remove all of the material and four years to recycle it. The redevelopment construction began in 2001, and, by 2002, the first stores were opening and the first homeowners were moving in. By 2006, over 5,000 people had made their homes in Stapleton and construction was finished on the neighborhood’s first school, William “Bill” Roberts Elementary School. Today the Central Park community is home to twelve different subdivisions and around 30,000 residents and development is still ongoing.

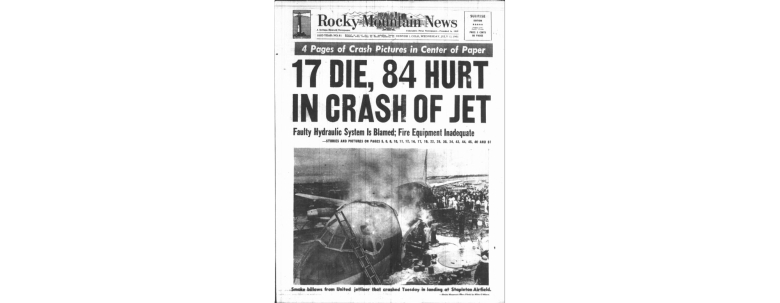

During Stapleton’s more than 65 years of operation, the airport experienced a slew of aviation successes and transported millions of passengers. However, the airport also saw its fair share of crashes. In its first 30 years of operation, there were no crashes at the airfield. Although, there were several planes in the 1950s that went down in residential areas of Denver, causing the Federal Aviation Authority to implement stricter safety regulations. Staplton’s no-crash streak was tragically broken on July 11th, 1961, when a passenger plane headed to Denver from Omaha crash landed at the airport. The Douglas DC-8-12 suffered hydraulic failure while en route from Omaha, which normally is not a major concern. The crew followed protocol for hydraulic failure but, while attempting to land there was another issue with the engine. The left-side engines continued generating forward thrust while the right-side engines generated reverse thrust, causing the plane to veer to the right. The plane hit the ground and all of the tires of the right side landing gear burst, sending the plane off of the runway and into a construction area where it subsequently caught fire. Sadly, 18 people died, including one on the ground, and 84 out of the 122 people on board were injured.

Stapleton remained relatively safe throughout the 1970s, with only three major crashes taking place that resulted in 12 minor injuries and no deaths. However, Stapleton’s streak was once again broken just eight years before the airport’s closure. On November 15th, 1987 Continental Airlines flight 1713 crashed during takeoff, marking Stapleton’s deadliest crash. The plane attempted to take off during a snowstorm, and, as a result of the harsh weather conditions, the pilot over rotated upon takeoff. This error caused the left wing to strike the ground and catch fire, killing 25 passengers and three crew members. The National Transportation Safety Board concluded that a build-up of ice on the wings contributed to the loss of control during takeoff, and the pilot's performance worsened the situation.

The control tower is one of the most recognizable remnants of the Stapleton airport. The first iteration of the control tower was put up in 1938, in order to alleviate aircraft congestion. The tower was six feet high, located on top of the administrative building, and was nicknamed the “Matchbox.” The air traffic controllers used radio to communicate with the planes that had radio and red and green lights for the ones that did not. The airport's sustained and rapid growth presented the need for renovations soon after the Matchbox’s completion. In 1940, construction of an entirely new control tower began. This new tower was 16x22 feet and had a 360° plate glass window. The control tower was once again renovated during the 1960s, under Mayor Newton’s Master Plan.

After the demolition of most of the airport and the development of the neighborhood, there were questions about what to do with the old control tower. Members of the community proposed ideas that included a community arts center, a museum, an observatory, and even a zipline. In 2017, Punch Bowl Social -a Denver based chain of amusement complexes- opened a location in the old tower. “We did it because it was the right thing to do, and to set an example of what we think are the right ways to behave with some of these historic structures,” said Robert Thompson, Punch Bowl’s founder and CEO. Punch Bowl Social abandoned the space during the COVID-19 Pandemic and in 2021, FlyteCo Brewing took up residence in the tower. FlyteCo Tower describes itself as a “one stop shop for beer and aviation enthusiasts” with “beer made by pilots for pilots,” making the control tower a perfect location.

Apart from the control tower, Hangar 61 is the most recognizable vestige of the old Stapleton Airport in Central Park today. The hangar was constructed in 1959 by the Ideal Cement Company, which was run by the Boettchers – a notable Denver family. Ideal Cement worked with architect Miles Ketchum to construct a hangar to house the company's private jet, a Fairchild F-27 Turboprop Airline. The Hangar was designed to showcase the modern and sleek applications of cement. Hangar 61’s unique mid-century modern style successfully achieves that goal. The hangar boasts a unique diamond shape with a thin roof supported by two giant concrete buttresses and grand sliding doors and is believed to be the only diamond shaped cylindrical arch thin-shell structure ever constructed.

After Stapleton’s closure in 1995, the hangar sat vacant and fell into disrepair. According to the Rocky Mountain News, by the mid 2000s there was a tree growing from the roof and the buttresses were riddled with bird nests. Despite the building's disheveled condition, Colorado Preservation Inc. took interest in Hangar 61 in 2004 for its connection to the Boettcher family and, more importantly, its unique design that is emblematic of the Stapleton airport’s golden age of aviation. In 2005, the building was listed as one of Colorado’s most endangered places and nominated for historic landmark status. That same year, Nelson and Ruth Falkenburg – a husband and wife team from 620 Corp Inc. – joined the project. Their company specializes in restoring historic buildings and they brought the hangar back to its former glory. Once Hangar 61 had officially been saved, the search for a buyer began. Arise Church Denver – formerly the Stapleton Fellowship Church – had been interested in the property since 2007, and after a three year hesitation, the church purchased the hangar and opened it up to their congregation in 2011. According to their website, Arise Church relishes their unique “privilege to put this magnificent structure to work serving the spiritual needs of Northeast Denver residents.”

The fight for inclusion in the skies has been an enduring battle since man left the ground. In 2022, the Federal Bureau of Labor Statistics reported that 93% of aircraft pilots and flight engineers were white. While the aviation industry has a long way to go, it can be argued that the fight for inclusion in commercial aircraft piloting began at the Stapleton airport. In 1937, Continental Airlines opened their headquarters in the Stapleton airport, and in 1957, the state of Colorado passed a law against discrimination in hiring. That same year, an African American pilot named Marlon D. Green applied to fly at Continental.

Marlon Dewitt Green was born in 1929 in El Dorado, Arkansas. As a child, Green showed interest in aviation and as an adult, he pursued those passions and joined the Air Force in 1948 – the same year the military was desegregated. Green was accepted into basic pilot training in 1950. During his time as an Air Force Pilot, he logged almost 3,000 hours of multi-engine aircraft flying time in multiple types of aircrafts. He was honorably discharged in 1957 and sought to transfer his military training into a career in commercial aviation. Despite his ample qualifications, Green was hard pressed to secure an interview for a job as a commercial airline pilot, until he was invited to interview with Continental Airlines after neglecting to mark his race on the application. Green made it to the final round of the interview process, in which he had over 2,000 more hours of flight experience than the other five candidates. Nonetheless, Green was not selected for the position.

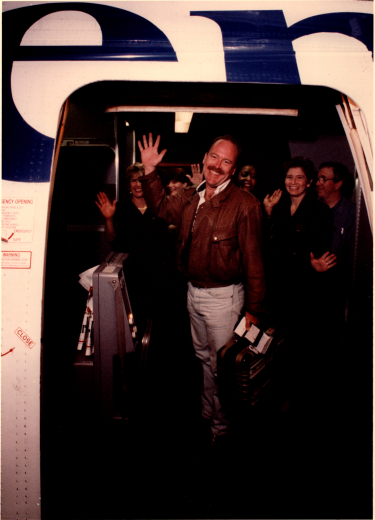

It was clear that Continental Airlines’ only reason for not hiring Green was his race, so Green took his case to the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission. The Commission endorsed Green's position but the Colorado courts ruled against him. Green and the Colorado Anti-Discrimination Commission appealed the court's ruling and continued to appeal for the next six years until the case made its way to the Supreme Court. On April 22, 1963 the Supreme Court sided with Green and the Commission, and ordered Continental Airlines to “cease and desist from such discriminatory practices and to give the complainant the first opportunity to enroll in its training school.” Green was hired by Continental Airlines in 1964 and flew with them throughout the remaining 17 years of his career, until he retired in 1978. Following his passing in 2009, Continental Airlines named a Boeing 737 after Marlon Green and at the same ceremony they also appointed Captain Ray Sean Silver to the position of pilot chief, the first black pilot to hold that rank within the company. This ceremony was an important recognition of Green’s bravery and sacrifice and highlighted the fact that his legacy and fight is still alive.

Ben Stapleton had been an integral part in the success of Denver's Municipal Airport, bringing thousands of jobs and dollars to the city via commercial and passenger air traffic. At the end of his long political career, the city of Denver renamed the airport to Stapleton Airfield to recognize the mayor's long standing commitment to the institution. After the airport’s closure and demolition, residential development began and the developers left the Stapleton name for the burgeoning neighborhood. However, the residents of the Stapleton neighborhood took great issue with this because Ben Stapleton was a demonstrably racist individual and corrupt politician. Stapleton was a card-carrying Ku Klux Klan member and close friend of Colorado Klan Grand Dragon, John Galen Locke. Stapleton drew heavily on the Klan’s political power in Colorado to secure his 1923 mayoral election, after which his cabinet was riddled with Klan members.

During his 1924 reelection campaign, Stapleton was more open than ever about his relationship with the Klan. At a rally he said “I will work with the Klan and for the Klan in the coming election, heart and soul. And if I am re-elected, I shall give the Klan the kind of administration it wants.” And that he did, making Denver hellish for any residents who were not White Anglosaxon Protestants. The Denver police force did nothing to investigate or prevent racial or religiously motivated attacks and threats; crosses were publicly burned and businesses and individuals were attacked, yet no official or officer took action. While Stapleton reduced his ties to the Klan after his first term and the KKK was largely driven out of Colorado, residents of Stapleton were still appalled by the association. Therefore in 2021, in the wake of national protests against police brutality, the Denver City Council acknowledged and supported residents’ long-held desire to change the name from Stapleton to Central Park– recognizing the community’s largest green space.

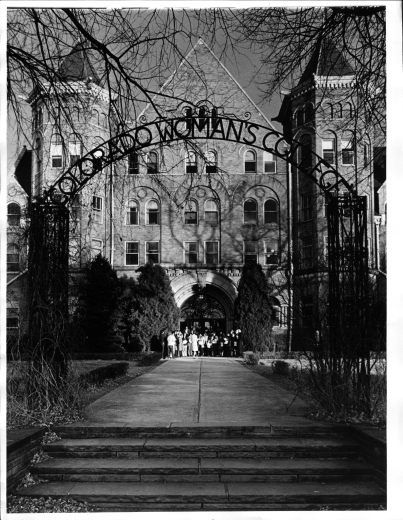

Located at the southern border of Park Hill and Central Park, the old Colorado Women's College campus is recognized for its beautiful historic buildings and the pioneering institution it once housed. The history of the Colorado Women's College (CWC) campus begins in 1886, when Reverend Robert Cameron approached Governor James B. Grant with the idea of establishing a women’s college – the first women's college in the western US. Cameron’s vision was to provide higher education for women in the Western United States under a Christian influence. The concept garnered local support, and in 1887, plans for the university were made by officials and funding was secured. In 1888, $40,000 worth of land for CWC was donated and incorporated into the city of Denver and the cornerstone of the first building was laid the following year. The college's establishment was met with enthusiasm from individuals across Denver, including former and problematic Colorado governor, John Evans, who remarked that he was “so glad to have a Colorado Vassar College."

Hard times in the west, exacerbated by the Panic of 1893, delayed the construction of the CWC campus. By 1909, the campus was finally ready to begin housing and educating students, and began doing so on September 7 of that year. Upon appointment, the first president of the CWC, Jay Porter Treat, described the institution's educational mission saying “we shall make paramount in our course the purpose to teach our students how to be good housekeepers, good wives, and capable mothers.” By the late 1950s, the school had adopted a more progressive approach to the education of its pupils. According to a statement released by the CWC in 1959, the college offered courses that focused on “three broad areas of education… personal and intellectual maturity, education for home and family living, and education for vocational activities.''

Despite the college’s recognized commitment to providing a well-rounded, Christian liberal arts education for thousands of pupils, enrollment began to fall in the late 1970s and the institution was hemorrhaging money. In 1982, the school’s assets were sold to the University of Denver (DU). DU continued to educate women at the CWC campus until 2001, when the historic campus became the Denver branch of Johnson & Wales University, and the CWC moved into a building on the DU campus. In 2015, DU decided to terminate the degree granting programs of the CWC for financial reasons. To maintain the CWC’s legacy of commitment to women’s education, DU opted to move forward with scholarship and equity lab programs. In 2021, Johnson and Wales sold the campus to the Denver Housing Authority and the Urban Land Conservancy, who have begun their mission of turning the old campus into a space that serves the community with affordable housing and job training for individuals who have criminal records or are suffering from homelessness.

In 1978, Treat Hall, a Richardsonian Romanesque building from the original campus, was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. In 2020, the impending sale of the Johnson and Wales campus allowed Historic Denver to asses the campus, and they concluded that “several of the buildings may be eligible to become individual Denver landmarks or to be listed on the National Register of Historic Places, while the collection of buildings and the spatial arrangement also has strong potential to become a historic district.” The organization is presently working on getting the beautiful and historic campus these accolades and protections.

A particularly successful venture in the Central Park development project was home and hospitality mogul Martha Stewart's line of houses with homebuilding company, KB Homes. Just two years after she was released from her notorious imprisonment, Stewart announced four home designs available for purchase in the budding Central Park neighborhood based on Stewart's own personal East Coast homes. KB homes was the largest home builder in Central Park and, according to the Rocky Mountain News, the line with Stewart sold 38% more homes than any of the 11 other developers in Central Park. President of the Colorado division of KB homes, Rusty Crandall, attributed the line’s success with “Stewart’s name [being] synonymous with beautiful design, attention to fine architectural detail and a renowned sense of good taste.” The special Stewart touch on the Central Park homes included: wainscoting, coffered and covered ceilings, distinctive crown molding, functional shelving, window seats, wooden mantels, nature inspired color palettes, and farmhouse style sinks. Despite the recession, these homes sold well and are still featured on many streets in the Central Park neighborhood.

During the initial development of the Central Park neighborhood, developers made a conscious commitment to green space and put together those areas first to ensure that this ideal was maintained. 1,100 of Central Park’s 4,700 acres are dedicated to parks and open space. The park for which the neighborhood is named is perhaps the premier accomplishment of the development team's commitment to open space. Central Park is the third largest park in all of Denver at 80 acres, making it more than double the size of Washington Park. Central Park is a hearth for the community with different spaces for gathering and recreation including an amphitheater, barbecue areas, athletic fields, and trails. While Central Park is by far the largest green space in the community, throughout the neighborhood there is a palpable commitment to maintaining natural spaces that serve the community, including a large section of the Sand Creek Regional Greenway, Founders Green, the Westerly Creek Greenway and many other areas.

Sources