Nestled in the inner southwest corner of Denver proper is the highly esteemed Baker Neighborhood. Structures such as schools and churches were built in the Queen Anne style and were prime examples of Victorian architecture. With its boundaries of West 6th Avenue on the north, West Mississippi Avenue on the south, the South Platte River on the west, and Broadway Street on the east, Baker has retained a rich history, not only in name, but in its remaining historic buildings and homes.

In 1985, the Baker Historic District was listed on the National Register of Historic Places. Previously known as “South Side” or “South Broadway,” the neighborhood received its name in the 1970s and was named after a junior high school. Often confused with its adjoining South Broadway area, Baker has become one of the most desirable areas for families and young professionals to reside in Denver.

Known as the “Byers Party,” William Newton Byers, John L. Dailey, and Edward C. Sumner were responsible for platting more than half of today’s Baker neighborhood. Similar to many adventurers interested in prospects for gold, the Byers Party and family made their way from Omaha to Auraria in the late 1850s. William Byers, a surveyor and farmer, acquired 160 acres of farmland along the east bank of the South Platte River, stretching from West Bayaud Avenue down to West Virginia Avenue. A log cabin was built in the area for the Byers family, but they ran into flooding troubles when the South Platte and Cherry Creek overflowed in 1864. The cabin ended up wedged between two cottonwoods and the Byers family had to be rescued by small boat. The land continued to be farmed, but the Byers family did not live in the Baker area for very long.

Byers was determined to establish the first newspaper in the area after being advised by his colleagues in Omaha. Many gold prospecting activities were not being documented, and Byers saw the potential for a successful publication. After purchasing a printing press and setting up shop in a log cabin, Byers learned there was another individual by the name of John L. Merrick who was planning to publish a Colorado paper of his own called the “Cherry Creek Pioneer.” The two proprietors learned of each other’s presence and both rushed to print their publications before one another. Both papers were published on the same day, but the Rocky Mountain News was published 20 minutes before the Cherry Creek Pioneer, making it the first official Colorado newspaper. The first printing of the Cherry Creek Pioneer was to be its last, as John L. Merrick sold his printing press soon after. The Rocky Mountain News continued to be published until 2009.

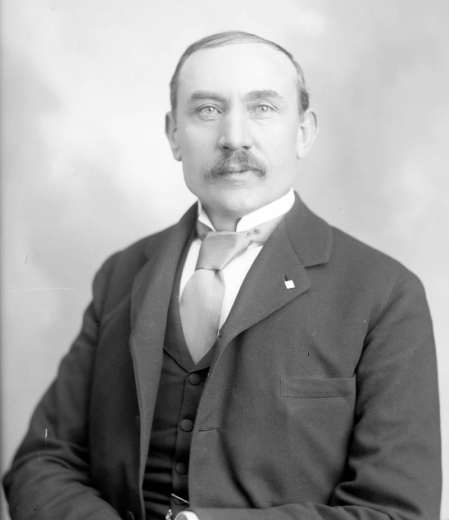

The acclaimed educator and administrator James Hutchins Baker was born in October 13, 1848, in Harmony, Maine. He taught at his first school at the age of eighteen after graduating from high school. He became principal of Yarmouth High in Maine soon after graduating from Bates College. In 1875, he resigned from Yarmouth and made his way to Denver to take the reins as principal of East High, which was previously known as Denver High School, and remained there from 1876 until 1892. His vast experience in education brought many fruitful changes to Denver Public Schools, and his influence was immediately noticed. With curricula reminiscent of his past experience in Maine and the integration of newer educational methods, Dr. Baker’s leadership also displayed positive changes in the school system, such as dramatic increases in attendance. As a member and president of multiple educational organizations, such as the State Teachers Association and the National Council of Education, he contributed many beneficial publications and books regarding educational science. In 1892, Dr. Baker was elected president of the University of Colorado until 1914.

In 1892, the 2nd District of Denver Public Schools erected a three and a half story building on 5th Avenue and Fox Street in the Baker neighborhood. At the time, the building’s architecture was viewed as having an unconventional design to accommodate a school. It eventually housed West High School and transitioned into Baker Junior High School. The structure cost $95,000 build and opened its doors with a library containing several thousand books. In 1925, the rapid growth of Denver forced the Denver Public Schools to relocate West High School three blocks away on 951 Elati Street, making room for a Junior High School.

Denver Public Schools replaced West High School with a junior high school and named it William Hutchins Baker Junior High School after the former principal of East High. In 1957, a modern design was desired for Baker Junior High and the building was brought down in favor of a new structure next door. The new building was designed by architects Jamieson and Williams. The process of having a new building erected next door inspired Baker teachers to include the building process in their curriculum. The architects and all parties involved in its construction were interviewed by the school’s student committee in order to gather information for their studies. Floor plans, scale models, and pamphlets were designed to display the building stages and the students’ involvement. In 2005, the school was converted into the Denver Center for International Studies.

Named after the Colorado pioneer William Newton Byers, the Baker area inherited an elementary school with constantly changing buildings and names throughout the century. In 1891, the first building for Byers Elementary School was built for a mere average of $6,000. It was known around the area as the “Old Tin School” due to its simple one-room tin architecture. The school house was a one-story structure with three windows on each side and was located on 104 West Byers Place. In 1902, the building was brought down for a larger building designed with a southwestern motif built by architects Gove and Walsh.

The new building included 8 classrooms, a cloak room, space for 550 students, and was built of steel and oil-finished Texas pine. The structure cost $40,000 to erect and rested on a real estate plot worth $51,000. The school’s name was changed to Alameda Elementary when Byers Junior High was opened in 1921. Alameda Elementary did well until the 1970s, when Denver Public Schools began phasing out smaller schools in order to accommodate the growing city. With dwindling enrollment numbers and a small building, the fate of Alameda Elementary was uncertain. By the early 1970s, Alameda Elementary closed and was left vacant until 1982, when the building was purchased by Charles Nash. He invested an average of $1 million in renovations and converted the building into condominiums.

On the northwest corner of 2nd and Elati sat the original Fairmont School. It was built in the early 1880s and was designed by architect William Quayle. The building housed 5 rooms, and its construction and land cost an average of $20,000. In this specific area of Baker, many residents of the neighborhood referred to Fairmont School as “Noah’s Ark,” since it was a popular place to socialize. Two of the school’s most prominent students were writer Gene Fowler and jazz musician Paul Whiteman.

Denver’s Board of Education acquired additional land around the Fairmont School and erected a new two-story building in 1924. The original building was brought down and its land was utilized for the playground. The gothic themed structure was designed by architect Harry Manning and cost $211,000 to complete. Artwork by J.H. Poage was featured inside the kindergarten classroom in the building. Silhouettes of animals and nursery rhyme characters decorated the hearth and frieze.

A year after the new Fairmount School was erected, a donation of books valued at $2,500 was added to the library collection. Ella Strong Denison, who had just retired from the school board, donated a collection of books in honor of her granddaughter who was an avid reader. Her granddaughter, Edith Swan, spent most of her life ill and passed away at the age of nine. The Edith Swan Library was named in honor of her memory. Ella Strong Denison not only provided a collection of books for the library, but also had a hand in the room’s decor. She continued to donate funds and artwork to the library for years.

In 1879, St. John’s Lutheran Church began when Reverend J. Hilgendorf assembled a German Lutheran group that congregated on 1846 Arapahoe Street. The church relocated to a smaller $3,000 home on Cherokee and West Fifth Avenue in 1886. Increasing numbers of churchgoers forced St. John’s to find a larger facility. Construction began on a new building on Third Avenue and Acoma in 1911. The building pictured above was designed by architect William Cove and had a steeple reaching nearly 100 feet tall. The temple was a $25,000 project that produced a cross at its peak, a beautiful birch interior, and engraved cornerstones. St. John’s number of worshippers was growing, and an academy opened in the Washington Park area in 1959. The church moved once more next to their school in Washington Park in 1968. After renting the West 3rd and Acoma building to other fellowships, its ownership was turned over to St. Augustine’s Catholic Church in the 1980s.

First Avenue Presbyterian Church started off as the Church of the Redeemer in 1889 and held services in a building on First and Broadway. With increasing members joining the congregation, the church relocated to West First Avenue & Acoma Street and changed their name to First Avenue Presbyterian in 1891. In 1905, architects John J. Stein and Montana Fallis built a new gothic themed building in the next lot. First Avenue Presbyterian attendance dropped in the 1980s, and the church developed new strategies to reach out to the community. Programs such as concerts, club meetings, and language classes for immigrants boosted the activity in the building. The church was also used by Baker’s neighborhood historic association as a meeting place.

Located on 6th Avenue and Broadway, the Broadway Stadium was designed to replace the Denver Wheelmen's Club facility, which was destroyed by fire in 1899. Known by locals as Broadway Park or Broadway Baseball Park, the 2,500 seat complex was the brainchild of baseball promoter George Tebeau. Denver’s professional baseball team, the Bears, joined the Western League in 1886, and Broadway Stadium was meant to stimulate interests in the team’s activity.

The complex was opened in April of 1900 with high stadium fences and a field that rested below street level. The park hosted professional and minor league baseball games as well as local high school football events. After disagreements between Tebeau and the Denver Bears about ownership of the franchise, the team refused to play in the stadium. All interest in the stadium ceased to be and it became defunct 20 years after opening its doors.

Built by C. Francis Pillsbury in 1936 as a WPA project, Fire Station No. 11 is the second oldest functioning fire station in Denver. Previously, Baker’s original Fire Station No. 11 was located on 301 Cherokee Street until it was replaced by the Art Deco building on 40 West 2nd Avenue. The new structure was built on a lot once owned by Denver Dumb Friends League founder Elizabeth Bates. The building is comprised of corbelled brick and displays three facade bays with the original carved sign bearing the “D.F.D No. 11” insignia in the center. The rescue unit responds to 2,000 calls a year and is currently home to fire engine 11 and a staff of four.

Designed by architect Montana Fallis, the Mayan Theater was poised to replace the fire-damaged Queen Theater. With its southwestern theme and Art Deco architecture, the Mayan Theater was erected in 1930 on 110 Broadway. Opening night was on November 20, 1930, and “Monte Carlo” starring Jeanette MacDonald was the first film screened. Other opening night festivities included a Native American presentation of a ceremony dedicated to the Mayan’s good fortune. A ritual of torches and droning drum beats throughout the theater was performed in order to rid the building of omens and evil spirits. The Mayan Theater was known for screening mostly new films and hosting weddings, fashion shows, and other live events. A store with novelties and snacks also contributed to the theater’s revenue stream.

By the 1970s, the Mayan became a B-movie theater with low price tickets. In dire need of renovations, attendance dropped as movie viewers preferred more modern theaters and their amenities. Changes in theater trends, shifts in ownership, and lack of funding for upkeep brought the Mayan close to the wrecking ball in the 1980s.

A local Union Bank purchased the Mayan and planned on knocking the structure down in favor of newer buildings. Local historians responded by developing the Friends of the Mayan Association in order to preserve the historic building. They were able to convince the city council to mark the Mayan Theater as a historical landmark. However, the Union Bank was persistent on demolishing the building and pulled a permit for the job. The Mayan wasn’t safe until Patrick Bowlen and Dick Landon purchased the Union Bank and the theater at the last minute. Renovations soon after brought the Mayan Theater back to shape and aided in deeming it the hotspot for independent and foreign films in Denver.

Originally owned by the Texas born Botte family, the Blue Bonnet Cafe opened its doors in the 1930s. Named after the Texas state flower, the cafe was one of the first establishments to acquire a liquor license after prohibition. The cafe initially served American cuisine until ownership moved to the Mobell family in the 1960s. The new owners introduced Mexican food to their menu, making the Blue Bonnet Cafe the choice location for innovative fusion dishes. The Blue Bonnet Cafe was renovated and relocated to 457 South Broadway in the 1990s and is now known as one of Denver’s oldest family-owned restaurants.

The Baker Neighborhood wasn’t without its challenges. In the 1960s, urban renewal plans such as the Skyline Renewal Project aspired to rid downtown Denver of sketchy bars and sex establishments. This resulted in the businesses relocating to South Broadway. During that time, courts were lifting restrictions on pornography and as opinions on the subject changed, a demand for the commodity developed.

By the 1970s, the South Broadway area was known for its wealth of adult movie theaters and taverns. Half of the locals were unhappy about the businesses while the other half were pleased with low rent and the free-spirited environment. By the 1980s and 1990s, interests phased out as technology and the Internet put a dent on brick and mortar adult businesses on South Broadway.

Though it appeared that efforts of urban renewal were harming the Baker Neighborhood, benefits of the movement were at hand as historic neighborhood organizations began taking off in the 1960s and 1970s. In response to many of Denver’s precious historic buildings being torn down, groups such as the Denver Landmark Preservation Commision and Historic Denver emerged to protect and preserve the city’s landmarks.

In 1978, City Hall designated Baker as a Neighborhood Revitalization District, making the area qualified for federal funded grants and loans. The neighborhood was slowly renovated by business owners, homeowners, and landlords. The gay community also took part in restoring the area with new additions such as businesses, clubs, and galleries all along South Broadway. These new establishments and organizations contributed in renewing the area, making Baker one of the more desirable locations to live in. In 2000, Baker was recognized as an official historic district in Denver.

Today, an easy stroll throughout the Baker Neighborhood will conjure memories of pioneers, educators, and architectural movements as their histories echo throughout the area. The neighborhood’s allure not only resides in Baker’s historic charm, but also in the newer developments being added to the area. As Baker evolves, modern buildings and businesses that endure will contribute to the neighborhood’s character. Will there be movements to preserve structures built within the last ten years? Will future generations strive to continue preserving Baker as we know it? It remains to be seen. One exciting prospect about Baker’s future is that the neighborhood provides firsthand experience with the past and the forefront of the future simultaneously.