Located on the banks of Cherry Creek in the heart of downtown Denver, Auraria is Denver’s oldest neighborhood, which predates the city’s establishment. Auraria today is the thriving campus of the Auraria Higher Education Center (AHEC) that opened in 1976.

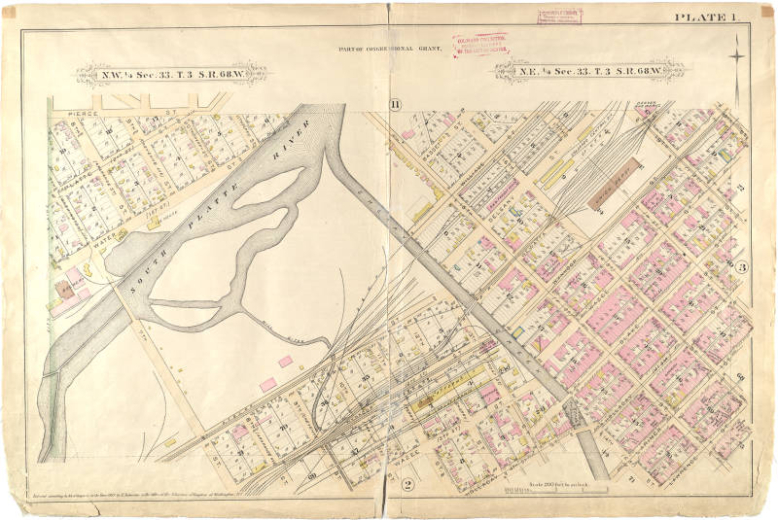

Auraria, Denver’s oldest neighborhood, predates the city’s establishment, and its history neatly encompasses the city’s founding, its development, and its redevelopment as a modern urban center. As a contemporary Denver neighborhood, Auraria is synonymous with the Auraria Higher Education Center (AHEC), which opened in 1976, and home to the University of Colorado Denver, Metropolitan State University of Denver, and the Community College of Denver. The neighborhood forms a rough triangle, bounded on the south by Colfax Avenue, with the South Platte River to the west and Speer Boulevard to the east, roughly the line of Cherry Creek, converging at today’s Confluence Park. Lincoln Park, immediately south of Colfax Avenue, follows the same west and east boundaries as Auraria, with Sixth Avenue as its southern boundary.

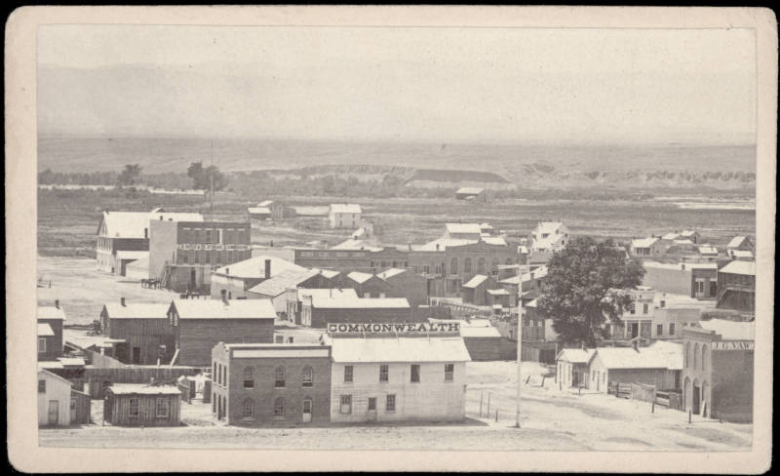

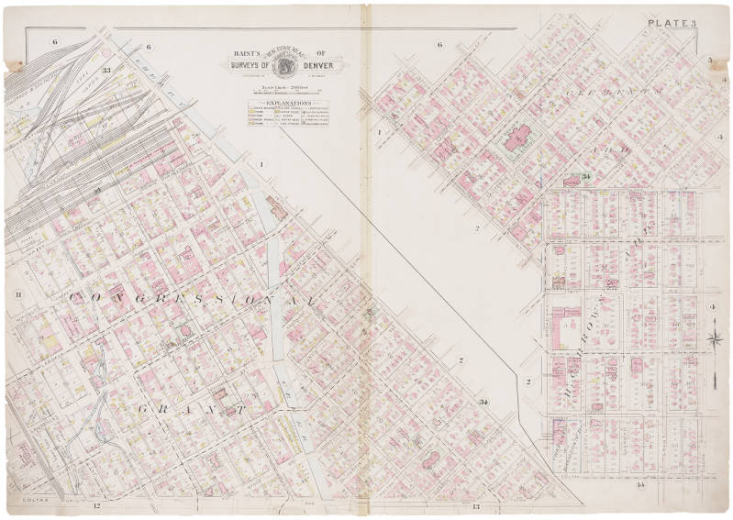

Auraria was established in 1858 by a small group of miners organized around the leadership of the Russell brothers, former residents of Auraria, Georgia, a mining town established after the discovery of gold in that state in 1828. ‘Auraria’ derives from the Latin term aurum, or gold, and reflects the fascination with gold found near the junction of the South Platte River and Cherry Creek. Not the first city to be imagined near the Platte and Cherry Creek (a distinction owed to the almost altogether unrealized St. Charles City), Auraria is perhaps the best claimant to being the heart of Denver. Auraria’s founders planned for a city of neat blocks, with regular lots, a 16-foot alley, and numbered streets perpendicular, and named streets running in parallel, to Cherry Creek. By 1859, a modest number of cabins and other buildings, host to a variety of businesses, had been established. And a still grander future for Auraria was imagined.

Within a few weeks of Auraria’s founding, a rival town, Denver City, promoted by William Larimer, had also been established on the banks of Cherry Creek. The two towns, and their respective boosters, entered a short-lived but acrimonious contest for supremacy; the futility of competition, and the possibility of cooperation, led to a merger in April 1860 and the establishment of a single urban entity: Denver. Shortly thereafter, the former city became known as West Denver in commonplace conversation, and Auraria was largely in disuse until the 1960s.

While the Auraria envisioned by its original boosters was never realized, the streets of Denver’s near westside became the epitome of what later generations would describe as a mixed-use neighborhood. Mills, breweries, warehouses, and other commercial enterprises sat alongside homes for working-class and middle-class families and rooming houses for single working men. In time, Auraria became a distinctly working-class neighborhood, peopled first by residents of old immigrant populations, and, after floods in the 1860s and 1870s, by a large and growing population of Central and Eastern European immigrants and their children. St. Elizabeth’s Catholic Church served a largely German congregation, while St. Leo’s served a largely Irish congregation. By the late-19th and early-20th centuries, Denver’s oldest neighborhoods, including Auraria, saw a significant reduction in their total populations. More extensive urban rail networks, followed by the advent of the automobile, matched the desire of many to move to new suburban homes outside an older, central core.

By the early 1920s, the ethnic nature of Auraria shifted from a mix of peoples of Central and Eastern European origin to a distinctly Hispanic neighborhood. Employed in various industries, these new residents of Auraria were variously from long-established Hispanic communities in southern Colorado and northern New Mexico, or relatively recent arrivals from Mexico. Householder directories of the decades from the 1920s through the 1960s reveal a preponderance of Hispanic surnames, with a smattering of households reminiscent of earlier residents, and durable connections to a place and its charms. St. Cajetan’s Catholic Church, the spiritual and cultural heart of Auraria’s Hispanic community, was constructed in 1926 at the corner of Lawrence and Ninth. As Magdalena Gallegos has so eloquently observed, "The lives of the Spanish-speaking peoples of Auraria revolved around their church. This was the place where they met weekly, made friends, and watched their children grow. It was the weekly social. The Hispanic people did not have much at that time; they did not have a public institution where they could mix and feel important. St. Cajetan’s was that place." By 1941, the concentration of Hispanics in Auraria, like the concentration of African Americans in Five Points, had become a matter of concern to city officials, who grew concerned over the stress and overcrowding of the homes and apartments of the neighborhoods. A city-sponsored housing project, Lincoln Park Homes, was established just south of Colfax Avenue in today’s Lincoln Park neighborhood.

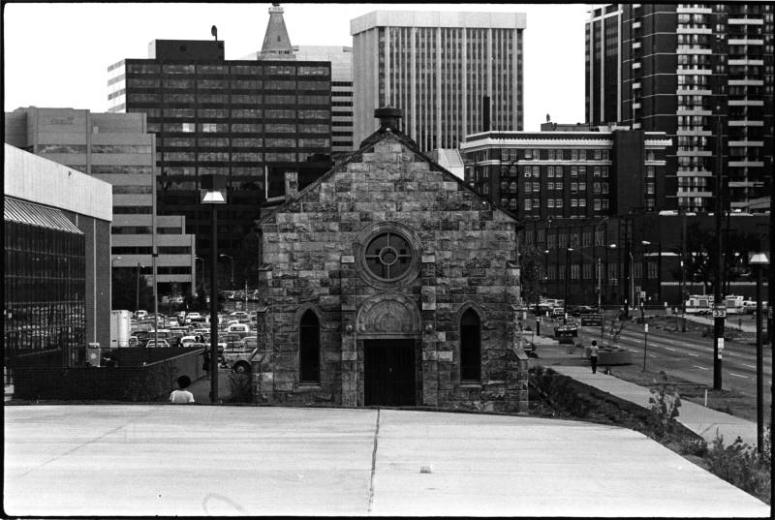

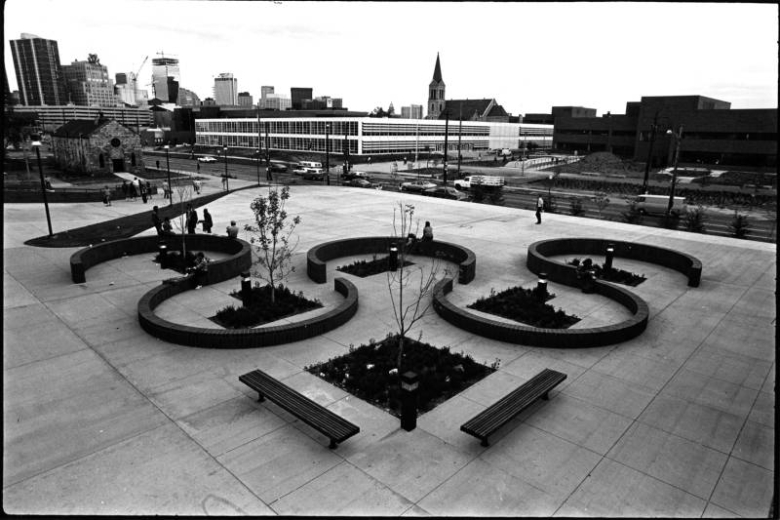

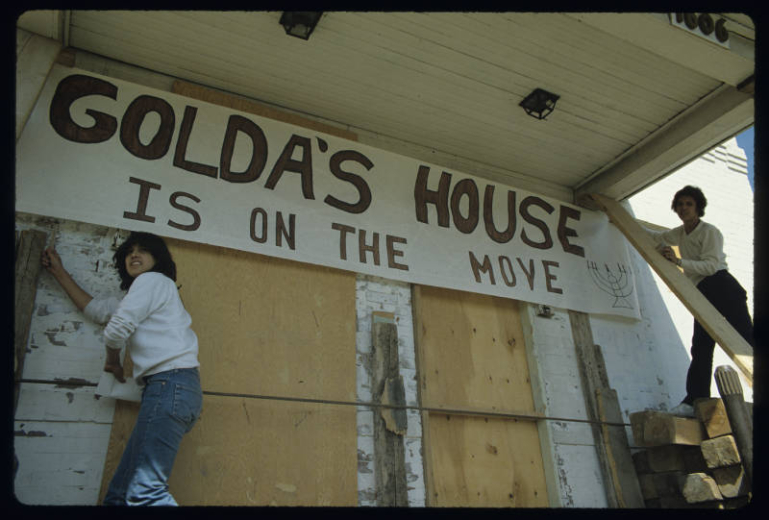

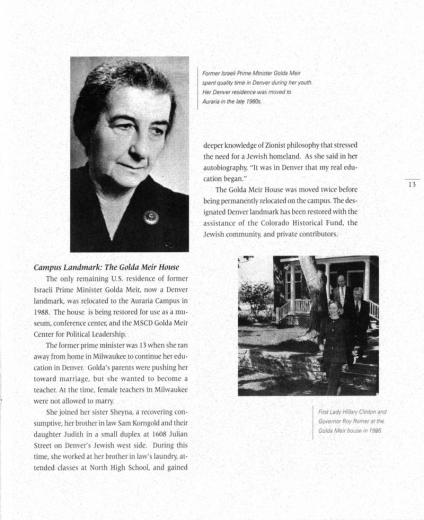

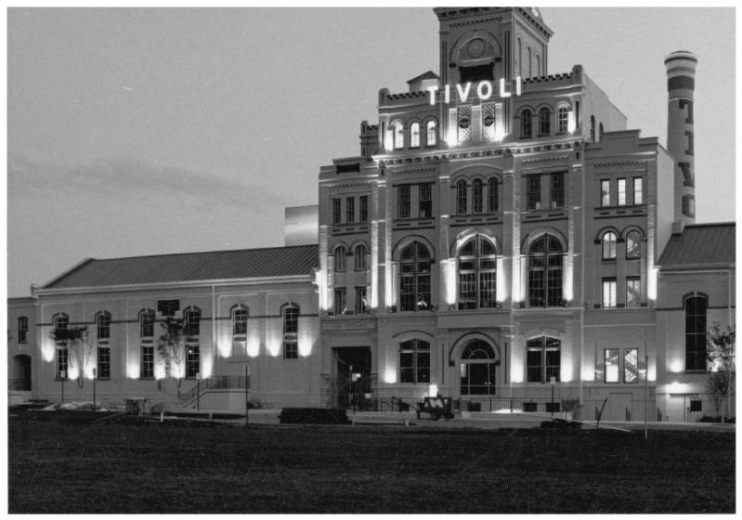

In June 1965, a devastating flood put much of Auraria underwater when the South Platte River spilled its banks after more than a foot of rain. As a result, the city undertook a comprehensive examination of the neighborhood and its circumstances, and began consideration of a comprehensive urban redevelopment. What followed, with the establishment of Metropolitan State College (later to become Metropolitan State University of Denver), and the desire to locate campuses of the University of Colorado and the Denver Area Community College on a central urban site, was a plan to clear Denver’s oldest neighborhood, and remake it as a modern urban campus. Money to buy land and relocate residents from the federal government, specifically Housing and Urban Development (HUD), was matched by a bond approved by a majority of Denver voters. Father Peter Garcia of St. Cajetan’s and angry residents formed the Auraria Residents’ Organization (ARO) to resist the displacement of neighborhood families, but ultimately their effort was unable to defeat the bond initiative. As a result, Auraria’s residents were displaced, with many moving to the adjacent neighborhood of Lincoln Park, itself a long-established Hispanic neighborhood now placed under an even greater strain with an influx of new residents. Relocations were complete by 1972; the Auraria campus was completed in 1976. Originally, a handful of structures deemed significant, including the Tivoli Brewery, Immanuel Episcopal Church, St. Elizabeth’s and St. Cajetan’s churches, were to be preserved. An effort to also preserve a portion of the original neighborhood, Ninth Street Historic Park, became a pivotal moment for the Denver’s historic preservation movement. Negotiations with the development agencies led to a groundbreaking in 1973, and shortly after the area had been added as a Historic Site to the National Register and declared a Denver Landmark. Today, a street of thirteen beautifully restored Victorian homes, five of them dated before Colorado’s statehood in 1876, and one commercial property, serve as campus offices and commercial space. A duplex, once the home of the fourth Israeli prime minister, Golda Meir, during her brief but important time in Denver with her sister and brother-in-law, was also relocated to the Ninth Street Historic Park.

Several times each year, often with the beginning of classes, a college student will appear at the reference desk of the Denver Public Library’s Special Collections and Archives, hoping to find some record of a parent, grandparent, or great-grandparent who lived in the neighborhood to support a claim to scholarships available to residents and their descendants. A name is sought in a city directory, or an address examined in a householder directory, and often the search reveals a family that once resided in Denver’s oldest neighborhood. A connection to Denver’s past is made, bringing together generations that lived, and now learn, in the heart of Denver.

The Auraria neighborhood is well known for the Auraria Campus. However, the neighborhood its self is very expansive and diverse containing many different businesses, parks, museums, religious and historical buildings. With the southern boundary along West Colfax Ave, running north along North Speer Boulevard and running south along the South Platte River the neighborhood forms a cone like shape.

“It was in Denver that my real education began…”

Copyright © 2004 Board of Regents of the University of Wisconsin System. All rights reserved. "Picturing Golda Meir" is published by University of Wisconsin-Milwaukee Libraries.

Golda Meir, as Israeli Prime Minister, epitomized the image of leadership. Through sheer determination and will power, Meir fought tenaciously for her chosen homeland in a field usually dominated by men. Moreover, Meir encouraged the idea among many that world leaders could develop from the lowest economic and most ethnic of environments. Born Goldie Mabovitch in Kiev, Russia, in 1898, Golda Meir fled with her family to the United States in 1906 to avoid religious persecution, eventually settling in Milwaukee, Wisconsin. At the age of fourteen, Golda--defying the wishes of her parents to give up her dreams of becoming a teacher--ran away from home to take up residence in Denver, Colorado, with her sister Sheyna and Sheyna’s husband and child. The residence, a duplex off of West Colfax Avenue on Julian Street, although small, became a center of sorts in Denver for Jewish immigrants of Russian descent, many of whom who had sought treatment in the Mile High City for tuberculosis. At the home, amid the discussions of politics, Meir developed her values and beliefs. She also met her future husband Morris Meyerson. In her autobiography My Life, Golda Meir expresses the significance of her Denver experience with the assertion that “my own future convictions were shaped and given form, and ideas were discarded or accepted by me while I was growing, those talk-filled nights in Denver played a considerable role.” In 1921, Golda and her husband immigrated to Palestine (modern-day Israel) and adopted a Hebrew version of their surname becoming the Meir’s. Golda quickly became active in politics and helped to establish the state of Israel. After holding several positions in the Israeli government, Meir served as Israel’s fourth Prime Minister from 1969 until 1974. Shortly after Meir’s death in 1978 the duplex on Julian Street was identified as her Denver home. The building stood empty until 1981 when it was learned that the house faced imminent destruction. Numerous citizen and preservationists groups began to raise funds to find a use for the duplex. Those efforts led to the relocation of the duplex to Habitat Park near the South Platte River to be used by the Audubon Society. Golda Meir House Relocation Preparation plans never came to fruition and, in 1985, the duplex was moved once again a short distance away on West Louisiana Avenue. During this time the house experienced attacks by fire and tornado, numerous episodes of vandalism, and frequent attempts at demolition by the city of Denver. By 1988, with support from various devoted individuals and organizations, the duplex made its final move to the Auraria Campus. The building received Denver Landmark Preservation Commission status in 1995. In 1997, upon completion of the restoration, renovation, and landscaping, Governor Roy Romer dedicated the new Golda Meir House Museum and Center for Political Leadership.

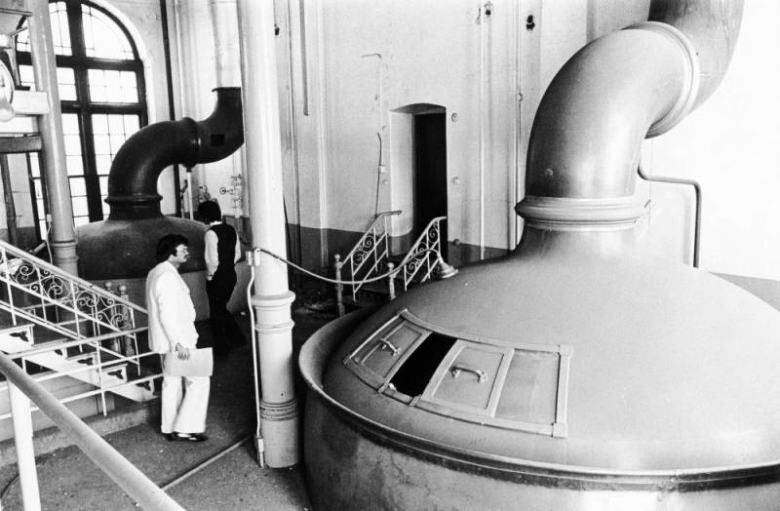

Located on the Auraria Campus the Tivoli Brewery was founded in 1860 by German born Moritz Sigi. With the Rocky Mountain Brewery founded a year before a rivalry developed between the two breweries. As both breweries changed names their competition continued as Sigi made improvements to his Brewery. Such as during the 1870s he began to construct a small building named “Sigi’s Hall” as well as digging the first artesian well in Denver. However, his improvements to the Brewery would cease in 1875 when Sigi was killed when his horses were frightened and overturned the carriage he was riding in. Upon his death Max Melsheimer took over the Brewery and called the business the Milwaukee Brewery. During the time Melsheimer operated the Brewery he added the corner building, the Turn Halle Opera House, and adjoining building, and the main tower building. As Melsheimer expanded the Brewery he has hit with a series of personal misfortunes. In 1881 he was charged with “making false reports” about his revenue, a year later his wife and three year old child passed away, when attempting to collect a bill a saloonkeeper “took after him with a billiard cue,” and eventually John Good foreclosed on the Milwaukee Brewery in 1900.

With the rationing of World War II the Tivoli Copper vats and steel work at the Tivoli-Union Brewery in Denver, Colorado, relapsed to using horse drawn beer wagons. In 1945 LoRaine’s second husband, Royce Kent, became the President of the Brewery while she took over as Chairman of the Board. Kent would then pass away three years later. By the 1950s the Tivoli’s production had steadily continued with the beer being sold throughout much of the west. In 1954 LoRaine married Russian singer Lubomir Vichegonov who was twenty-two years her junior. After their marriage LoRaine made her new husband President of the Tivoli but eventually cut him out of her will after infidelities on his part.

In 1962 a $1 million expansion was planned but never occurred due to the death of LoRaine in 1964. Her death set off a long and lengthy legal battle between Vichegonov and attorneys for the estate. Eventually the lawsuit was settled with undisclosed terms. The Brewery was then sold to Carl and Joseph Occiato owners of the Pueblo-Pepsi Cola bottling plant. Upon which they introduced a new product as “Denver Beer.” A year later a late spring flood filled the buildings with nine feet of water and caused $135, 000 in damages. As the new beer began to take off Brewery workers went on strike for six weeks. This strike seriously crippled the Tivoli. On April 25, 1969, with only half the operating staff from four years previously the Tivoli-Union Brewery closed its doors. After being abandoned for eight years the Tivoli Brewery was placed on the National Register of Historic Places in 1973. That same year the Denver Urban Renewal Authority (DURA) bought the dilapidated buildings to be used on the new Auraria Higher Education Center (AHEC). Eventually the entire complex was renovated and is now the Student Center on the Auraria Campus.

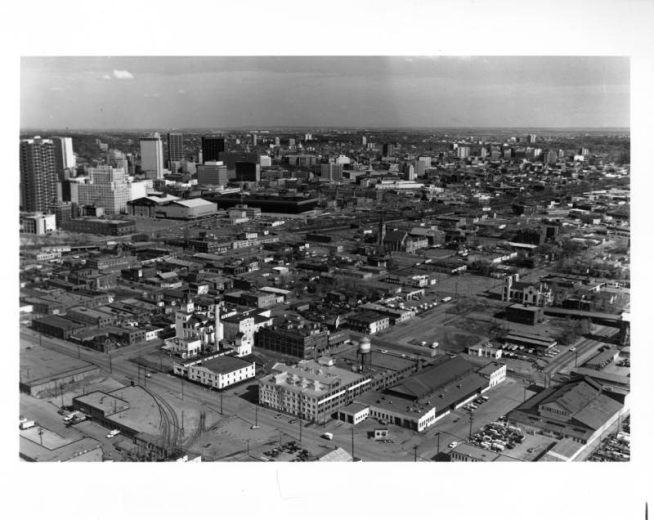

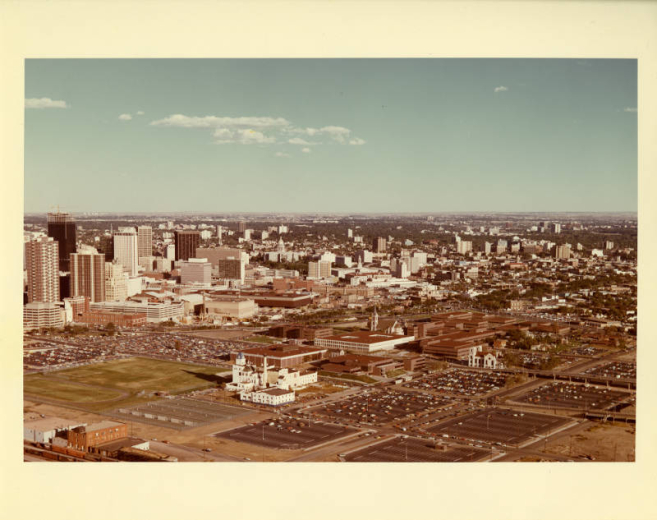

When the Auraria Higher Education Center campus was announced in 1968 the effect on the Westside residents was huge – in some ways immeasurable. The lowlands between the Platte River and Cherry Creek had always been home to immigrants and working class poor, small business and industry. It was a vibrant, colorful, diverse ethnic mix. By the 1960s it was still diverse but heavily Hispanic. Saint Cajetan’s Catholic Church, built in 1926 in a Mexican architectural style, was the beating heart of the community. While the neighborhood lacked in material goods, they were rich in tradition, kinship, culture, community. The site had been targeted as early as 1965 in the Mayor’s Platte River study as an urban renewal project. In 1956 the city changed the zoning designation to prohibit the construction of new residential housing. At the same time legislators and planners began to realize that the need for higher education opportunities and facilities in the Denver Metro area would be acute by the time the baby boom generation reached college age. In addition, business and industry were clamoring for a better educated workforce. A cynical person might speculate that the existence of a working class poor neighborhood – and Hispanic at that – on the very edge of a glittering new downtown was underutilizing the potential of the area. Seventeen sites were considered but study after study identified the Westside Auraria neighborhood as the most feasible site for the educational complex.

Auraria Residents (1956-1974) StoryMap

This visual tool combines a database of Auraria residents (1956-1974) and their addresses with a map of the Auraria neighborhood. A project by History Colorado and The University of Colorado Denver Department of Geography & Environmental Sciences.

Feeling left out of the process the neighborhood organized into the Auraria Residents Organization led by Father Pete Garcia, pastor of Saint Cajetan’s, but its fate was pretty much sealed. All that remained was the city’s scheduled bond issue election for November 1969. On the eve of the election, Denver Archbishop James Casey had a pastoral letter read from the pulpits urging all Catholics to vote “yes” for the bond issue. On Tuesday, November 4, it passed with 52 percent of the vote. Saint Cajetan’s Parish felt betrayed. A granddaughter of a displaced resident stated it more bluntly, “No one thinks they have a price. But everyone does. Even the church.” So, just like that, it was over. Saint Cajetan’s relocated to 299 South Raleigh Street and the neighborhood dispersed, a Hispanic diaspora, scattered throughout the city, its suburbs, and even beyond.

Now the site is home to the Community College of Denver, Metropolitan State University of Denver, and the University of Colorado Denver. Recognizing their sacrifice the descendants of those residents whose homes were taken are eligible for Displaced Aurarian Scholarships at all three schools. Those graduates have enriched not only their own community but the larger community as well. Out of the Westside experience grew the Coalition for the Betterment of the Westside, the New West Side Economic Development Corporation and other activist groups - all of which led to a larger and lasting Hispanic political presence. The importance of the residents’ stories – and their role in our history has been recognized. The Auraria community’s own Su Teatro produces the Westside Oratorio, a celebration of the seven generations that have called Auraria home – from the Arapahoe encampments to the Hispanic families uprooted in the 1970s to the students who currently occupy the campus. In the show’s final number, those cast members who have taken advantage of the scholarship step forward and introduce themselves, stating their major and date of graduation. The audience always erupts in cheers. And so their story continues.