~Written by Calli Force, University of Denver MLIS Practicum Student ~

This year marks the 25th anniversary of the Americans with Disabilities Act (ADA), and to commemorate the dedication of those involved in making this legislation a reality, the Denver Public Library's Western History/Genealogy department is currently processing a collection (Wade and Molly Blank Papers, WH2283) that intimately details the history and turmoil of the disability rights movement. Some of the foundational protests that ignited the movement took place on July 5-6, 1978, just around the corner from the Denver Public Library at Colfax and Broadway. Men and women of the Atlantis community, known as “The Gang of 19,” threw themselves in front of buses in an attempt to convey their disenfranchisement. This group blocked the intersection all day and night, chanting their mantra, “We will ride!” until representatives of the Regional Transportation District (RTD) were willing to talk about the absence of wheelchair-accessible buses. It was this initial protest that brought public light to the many other kinds of discrimination and abuse faced by the disabled community.

Wade Blank, a Presbyterian minister from Ohio, first found his passion for civil rights when he marched with Martin Luther King, Jr., in Selma, Alabama. But it wasn’t until 1971 when he began working as the Recreational Director of the youth wing for Heritage House, a nursing home for people with physical and mental disabilities, that he found his calling as an advocate for disability rights. Wade devoted his time and effort to improving the quality of life for the Heritage House youth and was resolute about liberating them from the less-than-ideal conditions of the nursing home. Heritage House refused to accept Blank’s insistence on helping the nursing home patients live independent lives, and he was fired for his progressive agenda. He refused to give up what he had started, so Blank founded Atlantis Community, Inc. in 1975 – an organization dedicated to providing free, individualized care to those in need including housing, meals, in-home care, and job training. Blank inspired a national movement for the differently-abled by advocating for equal opportunity rights ranging from humane, independent care to wheelchair-accessible public transit. In order for these people to live independently, they needed transportation, and so ADAPT was born.

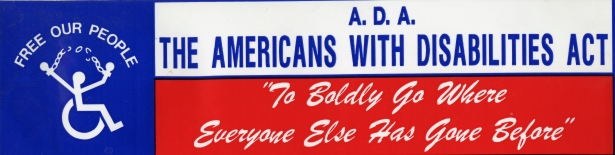

The overarching mission of the Atlantis Community was, and still is, to provide as many of life’s necessities—the necessities often taken for granted by those who do not live life with a physical or mental disability—as possible. Blank and those who resided at Atlantis decided to form an activist group to garner as much attention as possible for disability rights – ADAPT (American Disabled for Attendant Programs Today; once known as the American Disabled for Accessible Public Transit). The members of this militant-style activist group first focused their efforts on the Regional Transportation District (RTD), the origin of the initial rallies, which drew major attention to the cause. ADAPT members traveled across the nation protesting the American Public Transportation Association (APTA) and various bus companies, like Greyhound, to get wheelchair lifts installed on buses. Many ADAPT members were arrested during these protests, calling further attention to the lack of preparedness of local police departments’ inaccessible squad cars and facilities. Police officers erected makeshift barriers to detain the ADAPT members in wheelchairs because they had no other way of arresting and transporting the protestors. The second major wave of ADAPT protests targeted Social Security, health care policies, and Medicaid. Their ultimate goal was to obtain government support for attendant care and independent living funds. Eventually, ADAPT began protesting restaurants, schools, parking lots, post offices, housing communities, casinos, churches, and more. Wherever wheelchairs could not go, ADAPT was there to take action and demand access.

It took Blank and members of ADAPT decades to encourage legislation that demanded equal access to public transit, in addition to accessible public restrooms, airlines, and courthouses, for patrons using wheelchairs. Even after Blank’s tragic death in 1993, his family and the members of both the Atlantis Community and ADAPT continued his legacy by fighting against the discrimination that differently-abled people still face to this day.

Comments

Beautifully written.

Beautifully written.

Thanks for reading, Mark!

Thanks for reading, Mark! Calli Force did a wonderful job writing this blog post.

I would like to use a photo

I would like to use a photo for a presentation for the 30th anniversary of the ADA. Is there someone I can contact to discuss? Thank you!

Hi, Michelle! Please be in

Hi, Michelle! Please be in contact with Coi, our Digital Image Collection Administrator (photosales@denverlibrary.org).