This is the fourth in a series of “Curator’s Corner” posts: a little peek at the history of pieces in our art exhibit, A Visual Rendezvous: the Art Collection of the Western History and Genealogy Department. Guest Curator Deborah Wadsworth will give us the backstory (and maybe some juicy details) for select pieces that are currently on display on the Central Library’s 7th Floor.

A perfect mountain morning. Cool, pine-scented air. The birds are noisy and busy with their own concerns. Quietly, the artist sets up her well-worn pochade box, veteran of hundreds of plein air painting jaunts in England, France, Pennsylvania, New York. But this place is different. This is Colorado. This is home. She’s here on the Front Range Foothills and specifically on the ranch of friends she’s known since girlhood. She’s chosen her favorite medium again – watercolor – unforgiving, challenging, immediate. The light is glowing on the aspen leaves, on Mount Evans. Deftly she starts to work…

Elisabeth Spalding (1868-1954; both of whose names are frequently misspelled) came to Denver in 1874 when her father was designated Missionary Bishop of the Episcopal Church in Colorado and Wyoming, with oversight of New Mexico and Arizona.

Spalding’s life would always be split between her civic activities and her art. As the dutiful and hard-working daughter of a bishop, service to church and community was an expectation and not an option. Spalding taught bible studies, served as treasurer of the Saint Andrews Guild and hosted endless teas, socials, fundraisers and Aid Society meetings. She wrote articles, illustrated church publications, canvassed for worthy causes and worked tirelessly and anonymously on church projects. She was the chairman of the Church Art Commission and volunteered at St. Luke’ Hospital and the Home for Consumptives which her father helped found.

Perhaps her most important art project began in 1893. The instigator was Emma Richardson Cherry, who gathered together a small group of artists, which included Spalding, to found the Denver Artists Club (DAC). The group would grow over many years and with huge effort into the Denver Art Museum.

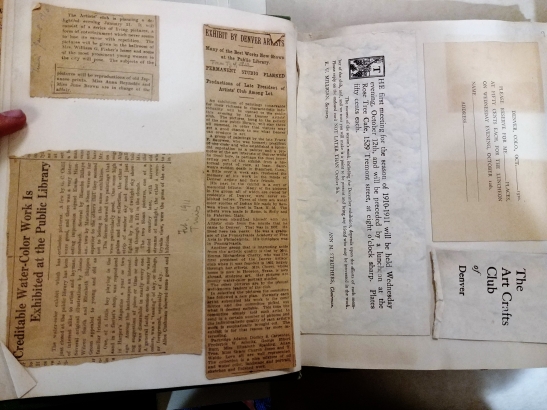

Starting in 1894, the DAC sponsored annual exhibitions. Since the DAC owned no building, its shows occupied a variety of temporary venues, finally finding a stable home in the DPL gallery, cementing a strong alliance between the arts and the Library. As Spalding later wrote, “We cannot say how much art owes to Mr. Chalmers Hadley, Denver’s exceptional librarian.”

Spalding specialized in landscape and still life. She worked in both oil and watercolor but because she loved plein air painting, watercolor predominated. Her favorite area was the foothills and she explored them persistently, usually trundling along in her beloved ancient Model T Ford. Spalding was one of very few artists who painted the foothills, a largely overlooked area of the state.

She was not a reclusive, rustic dilettante but a dedicated practitioner. She began her studies in New York in 1890 at age 22. She continued her studies under a variety of teachers including some of the best known artists of the day at the Cooper Union Art School and the iconic New York Art Students League. Her first exhibition was in 1892 in Philadelphia. From then on she exhibited widely and regularly, showing at the Paris Salon, the Société Nationale des Beaux Arts and in Stockholm, New York and Washington D.C. Her New Hogback Road was shown at the New York World’s Fair. Her exhibition schedule was arduous, even for someone not carrying her load of civic involvement.

Art exhibitions were an ongoing and integral part of Spalding’s life, but one in particular would stand out. In 1919, the Denver Art Association held its twenty-fifth annual exhibit at the Denver Public Library. Spalding exhibited as always and the titles of her paintings illustrate her devotion to the foothills: Foothills, Golden, Foothills in January and At the Foot of Lookout Mountain. All were well received.

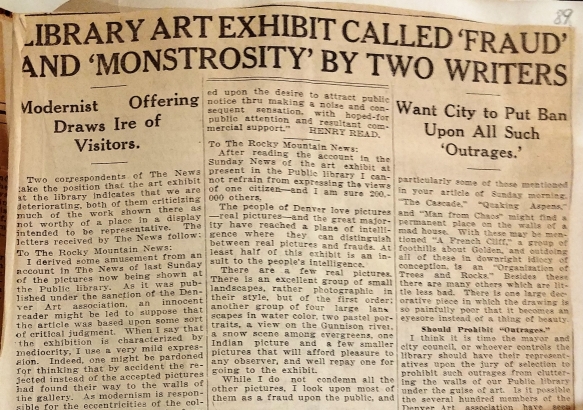

However, controversy would ensue from four newcomers: John Edward Thompson and his three students, Jozef Bakos, Augustyn Korda and Wtadek (Walter) Mruk, all from Buffalo, New York. Because of them, this show would become known as “Denver’s Armory Show.”

Buffalo-born Thompson had spent from 1902 to 1914 studying in Europe, where he experimented with the new methods of Cubism and Fauvism. Settling in Colorado after World War I, Thompson immediately joined the area’s art community. Upon invitation, he offered six of his more recent modernist works to the 1919 DAC show. His three students entered a total of seven works.

The response to the modernist paintings was immediate and furious. Local art critics and public alike were in an uproar. As difficult as it is for our jaded contemporary eyes to perceive, the works of Thompson and his students profoundly disturbed viewers in 1919 Denver. The Letters to the Editor pages of the Denver Post and Rocky Mountain News rang with denunciations. Thompson was compared to an anarchist and his paintings were said to have “colors never seen in nature” and “idiocy of conception.” Jozef Bakos’ painting Man from Chaos was described as worthy of a madhouse. The show was said to be a “fraud” and a “monstrosity,” and the whole thing demonstrated “bolshevism in art.”

In the midst of the tumult – the wildest art contretemps Colorado had yet seen – the quiet reasonable voices of Anne Evans and Elisabeth Spalding struggled to be heard. With mild mannered but staunch support, both women immediately responded with newspaper articles encouraging a reasoned and reasonable response to new art forms.

Spalding, well-traveled and well aware of current art trends, put a conversation-style discussion in the “Art Notes” column she edited for the Rocky Mountain News.

A questioner asks plaintively “Why do artists try all these new experiments. We don’t understand these new things.”

Spalding responds as “one of the artists”, “It would get dreadfully monotonous, wouldn’t it! I like to try new ways of expression. Variety is stimulating and constant repetition does make one dull!”

Another questioner says “Well, I like a picture that tells a story and I like plain facts.”

Spalding responds, “We artists have nothing against either the story or the fact, but we prefer color harmony without the facts to the statement of facts without color or harmony.”

The questioner then demands, “But do you really like these modern things?”

“If I didn’t, I wouldn’t paint them. The important thing is the sincerity of the artist. He must work with a sincere conviction. Whether the work is conservative or radical does not seem to us to be of primary importance, for honest work of the conservative helps to steady the radical with the sincere radical helps to broaden the conservative.”

This deeply-felt but quiet rationality exemplified Spalding’s lifelong behavior. She steadfastly held to her beliefs, but did so politely and with respect for all viewpoints.

Years later, when “madmen” Bakos and Mruk had gone on to found Los Cinco Pintores in Santa Fe and when “anarchist” Thompson had become a member of the Board of Trustees of the Denver Art Museum, Spalding was honored in 1943 by the City Club of Denver for her years of dedication and accomplishment, and for “distinctive achievement in painting”. Spalding was recognized for a lifetime of hewing to her own vision. In her own words, “the important thing is the sincerity of the artist.”

Interested in seeing more of Spalding's work? You can see a selection of her artwork on our digital collections site. Like all of the Western art collection, her paintings are available for study by the public.

A sidelight on Spalding’s art activities was her creation of comprehensive scrapbooks of newspaper clippings, exhibition brochures, and correspondence relating to the Colorado art world. These scrapbooks are in the DPL collection and are an invaluable resource for art historians.

![Title printed in watercolor on artwork.; Signed LL: "Elizabeth Spalding, May 1939"; Notes in ink on verso: "Painted on Mt. Morrison Road overlooking Soda Lake May 1939.; By Elizabeth Spalding 853 Washington Denver Colorado; Title 'Road Overlooking Soda Lake in May'; Invited by Mrs. Caroline Tower [for show?] at Woman's Club Denver [Monday] July 15, 1940 in a group of E.S. water colors"; Number #TIN-0656 on DAM inventory.](/sites/history/files/styles/blog_image/public/cdm_91286_0.jpg?itok=JjjXwerT)

Comments

Thanks for shining a light on

Thanks for shining a light on this important Colorado artist and her cohort. Can’t wait to stop in and see the paintings first hand.

Thanks, Tam! We look forward

Thanks, Tam! We look forward to having you.

What a pleasure to see such a

What a pleasure to see such a good article about Elisabeth Spalding. As a member of the Arts and Architecture Commission at Saint John's Episcopal Cathedral, I am happy to say that we own fifteen of Elisabeth's paintings (as well as a grand portrait of her father and our first Bishop) and have them on display in various parts of the cathedral.

Thanks, Ann! I am so glad to

Thanks, Ann! I am so glad to hear that you are appreciating and showing the paintings that you have. Sounds like a wonderful exhibition.

Hi Ann,

Hi Ann,

I know it’s two years later since this was published and I hope you’ve still online to read this. I’m doing some research on Jozef Bakos. Your review mentions the 1919 Denver Armory show wherein his painting, Man From Chaos, caused quite a stir. I cannot find any images online anywhere of this particular painting. Do you by any chance know where I might see a copy? Thanks!

Hi Jolan,

Hi Jolan,

Thanks for reading and commenting. Unfortunately, we haven't been able to find an online scan of this painting either. Perhaps it is in one of the published books on him? We have 2 in our collection (Jozef Bakos : an early modernist and Selections from the estate of Jósef Gabryel Bakoś (1891-1977), but cannot check them at this time due to COVID-19 closures.

Add new comment