Last month, civil rights activist Dolores Huerta made a trip to West Denver to urge participation in the upcoming 2020 census. “We have to say, this is the way we get back,” she told an audience at the Rodolfo “Corky” Gonzales Branch Library. “By being counted, by making sure that our names are known, that our faces are known.”

This is not a new tune. Concerns about the census and undercounting may be particularly high this year, but they have been part of the conversation for over a century.

Undercounting in the Census has Ramifications

The government uses census counts for a variety of purposes, which helps to explain why they can generate so much passion. Census numbers affect reapportionment of seats in the House of Representatives, redistricting of those seats, and allocation of federal funding to states for everything from healthcare to schools to roads.

A Long History of Census Disputes

As early as 1900, Denverites were questioning census numbers. A Denver Times article from that year announced, “Public opinion demands a recount.” It insisted that people had somehow been uncounted and cited various city records that belied the figure.

A similar article in the Denver Republican admitted that the official numbers fell short of expectations, but blamed it on the 1893 panic and the rise of suburbs.

That said, come 1910, the city was determined it would not be miscounted again. In February, Denver Municipal Facts included pages of census explanation. It featured information on enumerator qualifications and training, concerns about how to count “transients” and “foreign born labor,” and a list of the upcoming census questions.

After the disappointment of 1900 and hopes for the city’s growth, undercounting was clearly on people’s minds:

“An inaccurate census is always disappointing to the public-spirited citizens of any community and especially is this true of a city that has been making for a decade remarkable strides in building and general growth.”

Most striking about this 1910 breakdown is its glaring similarity to recent pushes for census participation. A copied speech from Chicago census supervisor Willard E. Hotchkiss includes a call to action:

“The one thing we have been trying to do is to bring the census before the people of the district in such a way that they will be disposed to co-operate with the government in securing the facts desired, that they will know that the questions asked are not of a nature to harm them, and that it is a matter of serious importance that the information be accurate and complete.”

This campaign to increase participation included work in schools and “social centers,” as well as advertisements in English and non-English language newspapers.

1970, 1980, 1990 and Denver’s Complete Count

Fast-forward to the 1970 census, and questions about the census numbers’ came around again. While previous concerns had been overall undercounting, this time the focus was on specific underrepresented groups.

While they estimated an overall undercounting of 2 percent in 1970, census officials admitted undercounting African Americans that year by almost 8 percent ("1970 Census Undercount May Have Cost Denver $1 Million," Denver Post, Jan. 7, 1979).

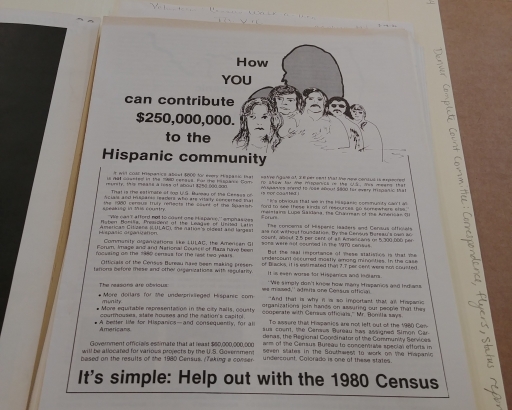

La Cucaracha, a community newspaper in Pueblo, Colorado, claimed that the 1970 census “failed to record large numbers of Chicanos, Puerto Ricans, Mejicanos, and Cubanos and other Latinos.” Even for the 1980 census, the paper cited ongoing fears around confidentiality and civil rights. How to win over a cautious community?

Thus, the Complete Count Committee was born. Based on a Detroit experiment, the Census department launched a program of community involvement. In Denver, this meant recruiting leaders and experts in typically miscounted communities, such as Hispanic, elderly, American Indian, African American and other populations.

As a Hispanic elected official, Richard Castro was among the community leaders associated Denver’s Complete Count and his manuscript collection bears witness for both 1980 and 1990. In 1980, he was a Colorado State Representative for Denver's District 6, and in 1990 he was Executive Director of Denver’s Agency for Human Rights and Community Relations.

Castro authored newspaper articles that outlined how an inaccurate count could harm Hispanic Americans in particular, and how a “full and fair population count [is] key to progress for Hispanics.” His papers also include flyers that break down the monetary value of being counted. “It will cost Hispanics about $800 for every Hispanic that is not counted in the 1980 census,” one states bluntly.

Yet, nothing is a silver bullet. There was optimism in Denver that the 1990 census might be significantly more accurate because of new technology, but the human element was still prevalent. As Denver worried that it might not top the "big city" 500,000 people mark, the Denver Indian Community Center took this opportunity to take a stand against historic and systemic discrimination. Wallace Coffee, director for the center and a member of the Complete Count Committee explained, “We have been constantly overlooked in regard to employment, serving on advisory committees, commissions or task forces that make decisions that affect the minority community” ("Indians, angry with Peña, urged to ignore census in city", Rocky Mountain News, Jan. 20, 1990)

Admittedly, the Native American community's concerns about censuses and government trustworthiness were founded in historical experience. Yet, Richard Castro urged them to stand up and be counted nevertheless. “If they don’t participate as a group, they will not be counted for 10 years. ...it’s going to affect them dramatically. Their community would benefit by a better count.” Regardless, Denver came in at about 460,000 people in 1990, but by 2000 it topped half a million, and it has continued to grow since.

Undercounting in the Census has Ramifications

Especially this year, the same old stories come back around. The Census Bureau cannot share personally identifiable data, even with other government agencies, but the possibility of a citizenship question (officially blocked by the courts) and fears of anti-immigration actions remain. Good or bad, the census is a powerhouse that can’t be ignored. The government uses census counts for a variety of purposes, which helps to explain why they can generate so much passion. Census numbers affect reapportionment of seats in the House of Representatives, redistricting of those seats, and allocation of federal funding to states for everything from healthcare to schools to roads. As a 1980 flyer spells out, "It's obvious that we in the Hispanic community can't afford to see these kinds of resources go somewhere else."

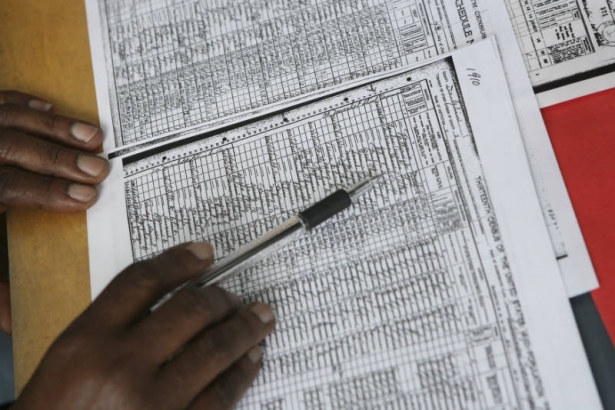

If the administrative and funding reasoning isn't enough, perhaps the future argument will help. As our Genealogy Tutorial explains, “the census is the backbone of American genealogical research,” so your descendants will thank you for participating. If you are concerned about your private information, rest assured that confidentiality remains paramount and individual data remains closed for 72 years; this year's census won't be available until 2092. If history is any guide, we will still be arguing over the census, even then.

Comments

Thanks for an interesting

Thanks for an interesting retrospective look at the census. It's nerdy, but I always look forward to filling it out.

Thanks for reading, Laura.

Thanks for reading, Laura. Just 21 days left until Census Day!

Genealogists may want to copy

Genealogists may want to copy the form and save them since it's going to be 72 years before they will be made public, aside from the statistics.

That is a good idea, Roger!

That is a good idea, Roger! Thanks for reading and sharing.

Add new comment